Hannibal, Sworn to Rome's Destruction

Posted on 15th May 2021

For 400 hundred years and more Rome would dominate and cruelly impose its will upon most of the known world. It stood as a colossus before which others were expected to kneel, but one man refused to bend his knee. Indeed, he swore an oath to destroy them. That man was Hannibal, and he would come perilously close to succeeding.

Born in 248 BC, Hannibal Barca was from the city of Carthage or modern-day Tunis which had been established as part of the Phoenician Trading Empire and unlike its great rival Rome its aim was never conquest but commerce. It didn’t even possess a standing army but relied upon mercenary soldiers under the command of Carthaginian Officers to fight its wars. One of these Officers was Hannibal's father, Hamilcar Barca, a General who had fought in the First Punic War (264-241 BC) against Rome that had resulted in the defeat of Carthage and the imposition of a humiliating peace.

No one felt this defeat more than Hamilcar Barca, a military man to his core who despised the greedy and cowardly Carthaginian Aristocracy who he blamed for their defeat. But he always hated the Romans more.

Carthage was a society which practised human sacrifice in honour of the Goddess Elissa, also known as Dido, whom it was believed had founded the city in 814 BC, and it was to one of these chambers of human sacrifice that Hamilcar took his son Hannibal.

Hamilcar had never had the opportunity to avenge the bitterness of defeat in the First Punic War and he now made his son, aged six, swear an oath in this most sacred of places. Speaking in the soft, high-pitched tones of a child Hannibal repeated with great solemnity: "I swear as soon as age will permit, that I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome”. Hamilcar then had his son recite the oath again and again until it was etched upon the memory of his youthful exuberance. A few years later, at his own insistence, Hannibal accompanied his father on his military campaign in Spain. He was not to see Carthage again for 40 years.

When Hannibal's father was killed in battle his brother-in-law Hasdrubal took command of the Carthaginian Army and under his tutelage the young Hannibal was to prove an exceptional cavalry commander. When Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BC, the popular Hannibal was seen as his natural successor. The Roman Historian Livy was later to describe the source of his popularity:

The old soldiers fancied they saw Hamilcar in his youth; the same bright look, the fire in his eyes, the same trick of countenance and features. Never was one and the same spirit more skilful to meet opposition, to obey, or to command”.

Hannibal's reputation soon grew as he set about consolidating Carthaginian power in the Iberian Peninsula. He was well known to the Romans who were also aware of his barely disguised antipathy towards them but arrogance was to ensure they underestimated him.

Rome, then still a Republic, had made an alliance with the city of Saguntum that was expected to act as an impediment to Hannibal's ambitions in Spain. In return for their help Rome had vowed to be their protector. Hannibal took this assurance of protection as a Casus Belli, and it was a war he had long sought.

For eight months he laid siege to the city of Saguntum hoping to lure the Romans into battle, but they would not be drawn. When the city finally fell he showed himself to be as ruthless as any Roman ordering its sacking and the massacre of its inhabitants - he was determined to show to the world that Roman protection meant nothing.

An outraged Rome demanded that Carthage recall Hannibal and serve him up to Roman justice. When they refused relations between the two States broke down resulting in 218 BC in the Second Punic War.

Free now to wage war as he pleased what Hannibal did next took the Romans completely by surprise. Leaving a garrison behind in New Carthage (Spain) he took the rest of his army, some 50,000 men, and advanced on Italy. He’d had to leave 11,000 Spaniards behind who refused to fight outside of their own country and then had to traverse the Pyrenees battling against hostile local tribesmen as he did so.

He then eluded a Roman Army that had been sent to intercept him in Gaul before achieving the remarkable feat of taking his army, including 37 War Elephants, across the Alps in winter.

But Crossing the Alps had taken its toll and his army suffered terrible hardship with thousands dying in avalanches of frostbite and of starvation. By the time he emerged on the Lombardy Plain his army had been reduced to only around 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. Indeed, it barely seemed that he had an army left with which to fight.

The Romans were suitably impressed by his accomplishment but remained largely unconcerned. They may have preferred to fight their wars on foreign soil but few doubted that they could easily defeat Hannibal's rag-tag little army but he was already trying to co-opt the local Gallic tribes into his campaign. They had recently been conquered by the Romans in a brutal and prolonged struggle were to prove ripe for recruitment. They were fierce warriors who would go onto form the shock troops of Hannibal's army. A minor victory over a Roman Army at Ticinus also helped convince many of the tribes to fall into line.

In very quick time Hannibal had managed to more than double the size of his army but it was a polyglot outfit made up of many races with different customs and languages which still had to learn to fight as a unit.

Following the defeat at Ticinus the Senate in Rome had recalled the Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus and his Legions from Sicily. His orders were to link up with the army of Publius Cornelius Scipio (Scipio the Elder) and crush Hannibal with overwhelming force.

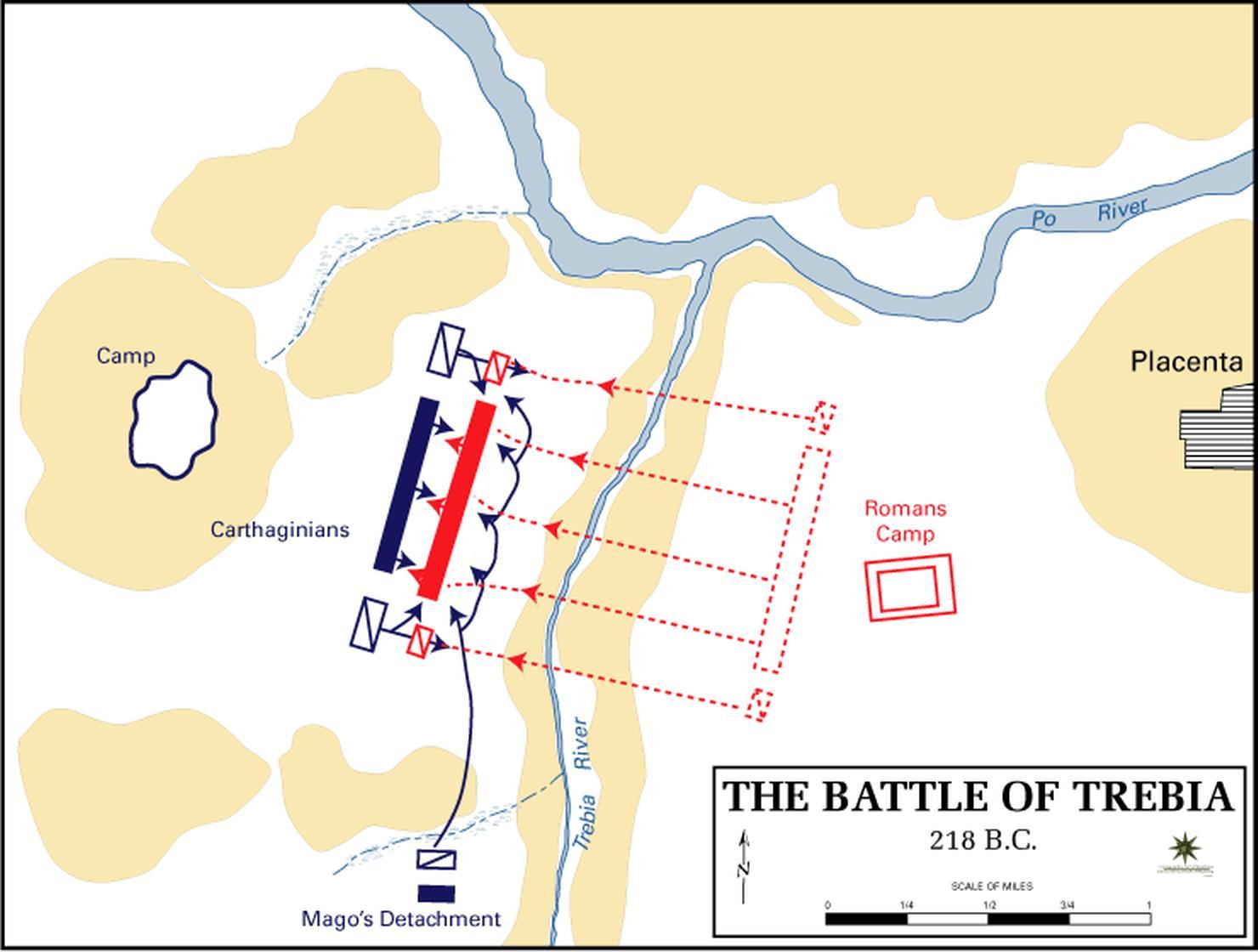

By December 218 BC, the two Roman armies were encamped on either side of the Trebia River in the province of Placentia or modern-day Piacenza. Sempronius was eager to engage Hannibal as soon as possible but Scipio, chastened perhaps by his experience at Ticinus was more cautious. On the eve of battle, he and Sempronius had a furious row.

Sempronius wanted to launch an all-out attack on Hannibal's position without delay but Scipio insisted they let things remain as they are and await the arrival of reinforcements. Sempronius demanded to know where these reinforcements were meant to come from and cast doubt upon his courage: “What good is there in further delay, you are cowering within your camp in the heart of Italy”. They parted acrimoniously.

Whilst the Romans were wasting time squabbling among themselves, Hannibal had been busy.He despatched his brother Mago with 2,000 cavalry to conceal themselves among the riverbeds. He then sent his Numidians to attack the Roman camp knowing full well that this would enrage even further the already volatile Sempronius.

Furious at being caught off-guard and desperate to lead his army against this impertinent barbarian he advanced his army straight into the trap Hannibal had set for it.

Having to cross the semi-frozen Trebia River on a bitterly cold day with the rain and snow sleeting down and visibility poor the Romans quickly became confused and disorganised as the Roman light-infantry faster and more mobile than the rest of the army became detached from the main force and were badly mauled by the physically stronger and more heavily armed Gaul’s of Hannibal's army.

The fleeing infantry now crashed into the main Roman formations following behind causing chaos whilst at the same time Hannibal's Numidian horsemen were routing the Roman cavalry on either flank. As the Romans began to withdraw in some confusion, Hannibal sprung his trap.

Mago's 2,000 cavalry previously hidden from view now emerged to cut off the Roman line of retreat and all discipline broke down as they fled in panic back across the Trebia River with more than 20,000 cut down or drowned as they did so. Scipio, meanwhile, watched events from afar but did nothing to come to his fellow Romans aid.

Following the disaster at the Trebia River the Romans were forced to yield much of northern Italy to Carthaginian control but they would soon be back.

They were aware that despite Hannibal's best efforts he had been unable to persuade Rome’s allies in Italy to abandon them and shorn of local support the Carthaginian's could only be an occupying not a conquering army short of supplies, constantly harassed and close to starvation.

In Rome, Scipio was heavily criticised for his inaction at the Trebia River and removed from command of his army but his failure to engage had at least ensured it remained largely intact and it was now placed under the command of Gnaeus Servillus Geminus. The remains of Sempronius's army were reinforced by two fresh legions and placed under the command of Gaius Flaminius.

Gaius Flaminius was an ambitious man who had made no secret of the fact he sought vGaius Flaminius was an ambitious man who had made no secret of the fact he sought victory for himself and only himself, and a triumph through the streets of Rome. His orders, however, were simply to secure the countryside around the city and make it safe for Roman citizens.

Flaminius was desperate for the opportunity to give battle and Hannibal aware of this sent forces to ravage the countryside around Rome making a mockery of his vow to protect it. By doing so he hoped to goad the reputedly hot-headed Flaminius into attacking him but much to everyone’s surprise he stubbornly refused to break camp. In response, Hannibal now performed the first recorded turning movement in military history to manoeuvre his army between Flaminius and Rome. His strategy worked.

Outraged and humiliated by this act of bravado on the part of a barbarian, Flaminius set of in hot pursuit despite being advised by his subordinates not to do so. Hannibal, in the meantime, was ensuring that the battle would be fought on ground of his own choosing, and that ground would be on the shores of Lake Trasimene.

As night fell on 23 June, 217 BC, Hannibal had fires lit some distance from where his army were encamped to confuse the Romans as to their exact location. Fooled into believing that Hannibal was too far away to pose any direct threat to his army the following morning Flaminius set off along a narrow defile on the bank of Lake Trasimene known as the Malpasso, or Bad Step, unaware that Hannibal's troops lay hidden in the woods on either side of them.

It was a hot, sultry morning, and a low mist lay upon the ground making visibility poor as the Roman Army with little room for manoeuvre marched in close order single file. As they advanced, Hannibal proceeded to cut off their line of retreat. He then launched a diversionary attack to draw the Roman vanguard away from the main body and split the army. As they did so the trumpets sounded, and the Carthaginian cavalry and infantry swept down from the hills to engulf the Roman army.

Taken completely by surprise and unable to form a battle line the Romans were forced to fight in the open, a form of warfare they dreaded, and their sense of dread was only reinforced by a sudden and severe earthquake that made it appear the Gods were against them. After three hours of fierce hand-to-hand combat, it was all over. More than 15,000 Romans had been killed and a further 6,000 captured. An army of 4,000 men sent to reinforce Flaminius was also wiped out, It was said that Flaminius himself was dragged from his horse and hacked to death by a Gaul who bore him a personal grudge.

At the cost of just 2,500 men the Battle of Lake Trasimene was a complete victory for Hannibal and his continued presence on Italian soil and the inability of anyone to do anything about it became a daily humiliation for Rome. But the disaster of Lake Trasimene at last woke Rome up to the threat posed by Hannibal - he was no barbarian bent on plunder he meant to wipe Rome off the face of the earth.

A panicky Senate now elected Quintus Fabius Maximus who had declared himself, to be the only man who could save Rome as Dictator for the coming year. His policy to combat Hannibal was to harass his armies but avoid any direct confrontation. In the meantime, he would ensure the continued support of Rome’s allies via a combination of bribes and intimidation while also adopting a scorched earth policy destroying everything in Hannibal's path. It proved to be an effective strategy but for many Romans who wanted to avenge the humiliations suffered at Hannibal’s hands it simply wasn't enough.

At the end of the year Maximus's dictatorship was not renewed and he was replaced by two Generals, Lucius Aemillus Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Their orders were to annihilate Hannibal's army and bring his severed head back to Rome.

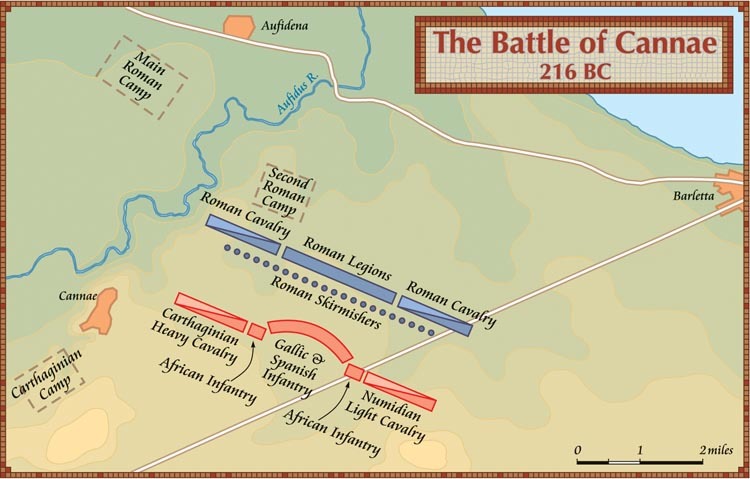

Although the Senate had been frustrated by the tactics of Maximus, they had to admit he had at least bought them time and they had used this time well to amass the largest army that Rome had ever put in the field. The recently elected Consuls Paullus and Varro would have 90,000 legionaries with which to oppose Hannibal's multi-ethnic Carthaginian army of 56,000 men.

The disparity in the size of the opposing armies caused unease among many of Hannibal's subordinates who were quick to voice their concerns and counselled caution, but he told them the next battle must be fought and that it would be decisive.

In the early summer of 216 BC, Hannibal captured the main Roman supply depot at Cannae and then set about ravaging the surrounding countryside with great ferocity putting as many people as he could to the sword. He was determined to let it be known that he did not fear this massive Roman army and that they could do nothing to stop him. As they advanced to meet him, he made no attempt to flee but instead harassed them at every turn.

As soon as they broke camp they would come under attack and even the simple journey to collect water from a nearby river became one fraught with danger. At one point Hannibal's cavalry even rode to the edge of the Roman camp simply to hurl insults at those inside calling them cowards and challenging them to come out and fight. But it seemed they had lost the appetite for battle for they did not retaliate but remained resolutely within their fortified camp, sometimes for weeks on end. There was it seemed a dispute over strategy.

Paullus wanted to engage Hannibal in one great and decisive battle but as earlier at Trasimene, Varro remained more cautious and wanted to play a waiting game. Finally,the decision was taken to engage Hannibal’s army but Varro it seemed could not be swayed, and according to Hannibal's own reports it was Paullus alone who was to oppose him at Cannae.

On 2 August 216 BC, a blazing hot day, the opposing forces formed up open plain at Cannae.

Hannibal had positioned his army directly in front of the Aufidius River, a perilous thing to do as it cut off any potential line of retreat. A view only reinforced by the fact Hannibal knew the Romans would seek to fight a traditional battle and destroy the centre of his line. So here he placed his best infantry 8,000 Gauls and 8,000 Iberians to be supported on either flank by 6,000 Libyan and 5,500 Gaelutian light infantry. These men would be expected to absorb the full force of the Roman attack with the River behind them serving as their anchor.

As the Roman assault pressed in on the Carthaginian line, Hannibal would to use his cavalry to disperse their weaker Roman opponents and envelop their army from the rear. But it all depended on his centre being able to hold out against the full-weight of the Roman Army.

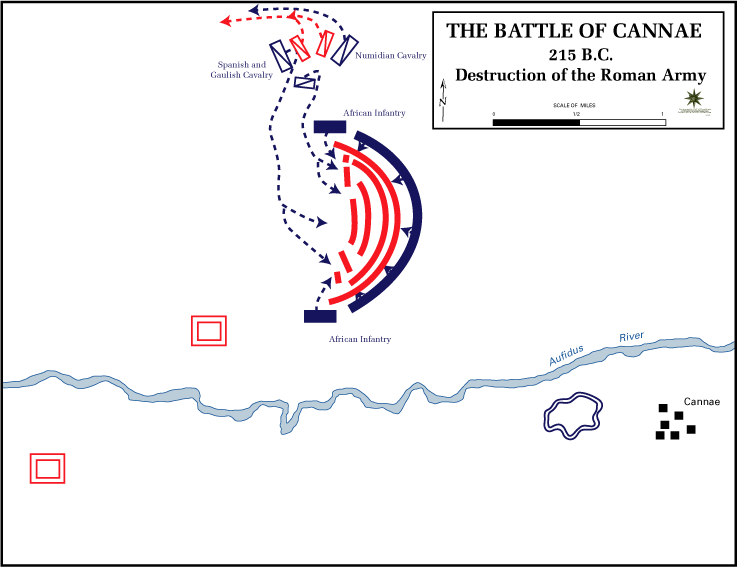

For much of the day the battle lay in the balance and if anything it was a Roman victory that appeared imminent but as the pressure began to tell and the Carthaginian infantry were gradually forced back a deep wedge was formed in the centre of their line. Witnessing this, the Romans committed more and more men to the attack.

Hannibal however, who was fighting alongside his men to ensure that order was maintained had also been cleverly dispersing his troops to either flank so that his formation began to take on a crescent shape. He knew that with the river to their backs his men could not flee and would either have to fight or die.

The Carthaginian cavalry which had earlier cleared their opponents from the field now began to attack the Roman rear. As they did so Hannibal ordered his troops on either flank to close in. The deep wedge that the Roman infantry had cut into the Carthaginian centre now began to work against them as squeezed into a smaller and smaller space until they hardly had room to wield their weapons – they found themselves not only surrounded but crushed.

The Historian Polybius described how the Romans were cut down where they stood: “Many were crushed to death, some in their desperation even tried to tunnel themselves out of the melee”. Livy, in his History of Rome elaborated further: “So many Romans were dying . . . some whom by their wounds, pinched by the morning cold, had roused, as they were rising up, covered with blood, from the midst of the heaps of the slain, were overpowered by the enemy. Some were found with their heads plunged into the earth, having thus, as it appeared made pits, and having suffocated themselves”.

The slaughter continued until nightfall.

The massacre at Cannae was a catastrophic defeat for the Roman army with more than 50,000 of their best men dead on the field including Paullus, Geminus, 80 Senators and 300 of Rome’s nobility and highest-ranking citizens. What remained of the army, some 14,000 men fled in total disarray to the sanctuary of nearby Canusium. Hannibal had lost just 8,000 killed mostly from among his Gallic and Iberian infantry.

The Battle of Cannae was Hannibal's masterpiece but rather than being the high-water mark of his military career it merely heralded the beginning of his troubles. He was desperate to finish Rome off and avenge Carthage's humiliating defeat in the First Punic War, but he could not do so with the forces at his disposal. Nevertheless, the signs were good with for the first time Rome's allies in Italy beginning to desert her including the significant City State of Capua. While learning of the defeat King Philip V in Macedonia declared war on Rome. What Hannibal needed more than anything, however, was the support of Carthage itself. He needed men, he needed supplies, and he needed them now.

In a dramatic gesture he had the rings of every dead Roman removed and placed them in a bag. He then sent his brother Mago to Carthage to announce the victory. As he did so he emptied the bag on the Senate House floor so that the politicians could see for themselves the magnitude of what had been achieved. They were suitably impressed but after much debate no further help was forthcoming. Hannibal and his army would be left to fend for themselves.

Upon receiving the news that the politicians in Carthage had abandoned them Hannibal's subordinates urged him to march on Rome itself. When he declined to do so the Commander of his Numidian Cavalry, Maharbal, told him: "Truly the God's have not bestowed all things upon the same man or thou knowest indeed, Hannibal, how to conquer, but thou knowest not how to make use of your victory”.

But Rome was a massive city with strong defensive walls and a population of over 150,000. The countryside still remained hostile to him, and his own army now numbered less than 50,000 and he knew that to march upon Rome and then be unable to take it would provide his enemy with a massive psychological victory and undermine his aura of invincibility. So instead of besieging the city he sent emissaries to negotiate a peace settlement but in adversity the Romans now showed great resilience and they were in no mood to parley.

“Never before while the city was still safe had there been such excitement and panic within its walls. I shall not attempt to describe it, nor will I weaken the reality by going into details . . . there was no longer any Roman camp, any General, any soldier in existence . . . almost the whole of Italy lay at Hannibal’s feet. Certainly there is no other place that would not have succumbed beneath the weight of such a calamity”.

The entire male population of the city had been mobilised for war with even the more trustworthy among the slaves being armed. Any talk of peace was now banned and Fabius Maximus was again elected Dictator. He now employed the same tactics that had been so successful the previous year. Then it had been considered dishonourable and not the Roman way now it seemed the only option as he placed small armies in the way of Hannibal to slow his movement and restrict his ability to range freely across Italy. He blocked passes, destroyed crops, and slaughtered livestock, but stubbornly refused to commit to battle.

Hannibal continued to defeat those armies not directly under Maximus's command that dared to confront him most notably in 212 and 208 BC, but he could not engineer another Cannae, and all the time his forces were growing weaker and those of Rome stronger. He was also handicapped by the fact his subordinate commanders were never as effective when not under his direct command and one of these was his brother Hasdrubal in whom he had always shown unjustifiable faith. Defeated in battle, Hasdrubal's head was cut off, placed in a bag, transported across Italy and tossed into Hannibal's camp. It was a personal tragedy that affected him deeply.

Regardless of all his triumphs and humbling of once mighty Rome the Carthaginian Ruling Elite made up of a hundred or so of the richest nobles resolutely refused to support him. Their overriding concern was always one of commerce and under the sway of Hannibal's great rival Hanno all attempts by his allies in Carthage to reinforce him were blocked. As far as they were concerned his war in Italy was nothing more than a personal vendetta against Rome.

In 203 BC, after 15 years in Italy, Hannibal was recalled to Carthage to defend it against the Roman army of Publius Cornelius Scipio who shared the name of his disgraced father defeated at Ticinus and who had refused to fight at Trebia.

Scipio Africanus as he would become known had fought against Hannibal many times and was a great admirer. On the eve of battle, he invited Hannibal to dinner on the pretext of peace negotiations but the truth was he just wanted to meet the great man. The negotiations went nowhere but they enjoyed a convivial evening during which Scipio was to discover that Hannibal was not shy of his genius.

The following morning the two armies gathered on the plain at Zama.

Hannibal's army comprised of a small core of veterans and conscripts from southern Italy pressed into service. His elite Numidian Cavalry, seeing the way the tide was turning, had changed sides. The Roman army was the best they could put in the field.

So despite being numerically superior Hannibal's army was of doubtful ability or indeed loyalty. Even so, the battle was hard fought and a close-run thing only being decided late in the day when the Roman cavalry early swept from the field re-emerged to cut a swathe in the Carthaginian rear.

With the defeat of Hannibal so was Carthage defeated. They had nothing with which to defend themselves and regardless of his genius even Hannibal could not triumph without an army to fight with.

All Rome now expected Scipio to plunder the city and burn it to the ground but instead his terms for surrender were surprisingly lenient Hannibal was even permitted to run successfully for the Office of Suffete, or Chief Magistrate, and he was to prove as able a politician as he was a General. He restored the power of the Magistracy appealing directly to the people for support rather than the nobility who had always spurned him. Without them he cleaned up the city's politics, put an end to financial corruption and restored it to prosperity.

This latter achievement unnerved the Romans however, they had not forgotten him and the phrase "Hannibal is at the Gates" was still used to force unruly children into compliance. So, 12 years after his defeat at the Battle of Zama, Rome demanded that Carthage surrender Hannibal to their care but before any action could be taken against him Hannibal went into voluntary exile. He was now to all intents-and-purposes a man on the run, a mercenary soldier, a General for hire and he was warmly received wherever he went but fear of Rome saw him showered with honours but offered few positions any real power.

One of the few opportunities that came his way was when he served the King of Bithynia and later when he commanded the Saleucid Fleet. In one battle he devised a plan whereby the enemy ships were bombarded with pots crammed with poisonous snakes that shattered on impact. They sowed panic among the crew who then abandoned their ships. A decisive victory followed but it was to be his last great triumph for all the time that Hannibal lived his nomadic existence the Romans were closing in. Finally, in 181 BC, he was tracked down to the small town of Libyssa on the shores of the Sea of Marmara.

As he sat on the porch of his villa, he could see the Roman troops approaching He quickly penned a last letter: "Let us relieve the Romans of the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man's death”. He then took the poison he had for so long carried with him.

Hannibal, the man who had been sworn to Rome’s destruction was dead, aged 63.

Thirty-five years after Hannibal’s death Carthage was once more at war with Rome.

After a siege lasting almost three years in 146 BC the city finally fell to their oldest enemy who destroyed it utterly. It had been a gallant defence, but they had no Hannibal.

Throughout its history Rome was to face many formidable enemies – Mithradaites, Arminius, Boudicca, Vercingetorix and Attila the Hun among others but none was ever as formidable as their first, Hannibal. He defeated them time and time again and on their own soil deprived of ultimate victory only by the lack of support from those in whose interests he fought.

He had sworn as a child to destroy Rome and had failed - but it had been a glorious failure.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, War

Share this post: