Henry VII: The Forgotten Tudor

Posted on 6th January 2021

He killed the tyrant, usurped the throne and in doing so ended the Wars of the Roses changing England forever yet, unlike the Dynasty he spawned, he remains largely forgotten.

The future King Henry VII was born on 28 January 1457 in Pembroke Castle the son of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, and his wife Lady Margaret Beaufort, his birth both difficult and protracted was only less traumatic perhaps, than his conception.

Lady Margaret, small and delicate, had been made pregnant by her husband less than a year after marrying him aged just twelve in an act of child rape that was deemed unacceptable even then. Indeed, so damaged was she by the assault that despite the safe delivery of a son she would never conceive again. That was the price she paid for her husband’s amorous attention in an age when a woman’s fecundity was both her value as a bride and her security against harm. That he would never darken her door again, dying within a few months of the plague was scant recompense for the damage he had done but the son he had sired so brutally would be.

It was only through his mother that the young Henry had any claim to the throne at all, tenuous as it was. She was the daughter of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset the third (and bastard) son of John of Gaunt who was in turn the fourth son of King Edward III. Her marriage to a Tudor, servants of the Crown rather than in the line of succession may have appeared to some a sign of diminished status but not in her eyes. She knew the value of her son to the House of Lancaster and that it would only increase over time. If nothing else, her unceasing work on his behalf would see to that for she never doubted her son’s right to the throne even if few others for now at least agreed.

With Edward IV securely on the throne it appeared the family squabble between the Houses of Lancaster and York had been settled once and for in the latter’s favour, and maybe it would have been had events taken their expected course, but years of idleness and over-indulgence had taken their toll on the once physically impressive King. Even so, his death on the 9 April 1483, at the age of just 40, was both sudden and unexpected.

Perhaps aware of his failing health Edward fretted over the fate of his sons, the 12-year-old heir to the throne Edward, Prince of Wales and his younger brother Richard, Duke of York. Who could he trust to do right by them? Little had been forgotten or forgiven from the decades of conflict neither had ambition been tempered or dulled by the humiliation of defeat - many a villainy lay hidden behind the mask of friendship. Who then, in the event of his death would protect his family and preserve the dynasty?

The one man he believed he could trust was his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who had never been less than loyal and had indeed harmed his own reputation by his willingness to do the King’s dirty work. He was also a good uncle to his nephews, or so it seemed. It gave Edward peace of mind to know that in case of his death his son’s would be given over to his brother’s care.

With little reason to doubt his sibling Edward named him Lord Protector of England in the event of his passing little realising that Richard had long suspected him of being illegitimate, the result of a liaison between his mother and a common soldier. He had kept his suspicions secret but if his brother was indeed only his illegitimate half-brother then his sons were illegitimate also, and the throne his by right as next in line.

With the King dead he now acted on his suspicions seizing the young Prince of Wales as he made his procession south to London for his coronation executing those who had been assigned to escort him. Learning of this Edward IV’s widow Elizabeth Woodville, or the sorceress, as Richard referred to her, fearing for her own life and those of her remaining children sought sanctuary in Westminster Abbey.

Upon reaching London, Richard had the young King in-waiting confined to the Tower for his own protection where he was soon joined by his younger brother whom he had bulled his mother into handing over to his dubious care.

For a time at least, the young princes were seen to play regularly in the grounds of the Tower but soon nothing was seen of them at all. The rumour was they had been murdered and it was a rumour readily believed. Richard had long been his brother’s willing executioner after all, few doubted his ruthlessness.

Unable to prove that the former King was his mother’s bastard son Richard instead focussed on the illegitimacy of his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville producing evidence of a contract he had signed to instead marry Eleanor Butler, the future Lady Talbot, insisting it still had legal force. If so, Richard would be justified in removing his brother’s children from the line of succession thereby making him the rightful heir. It was enough for him to cancel the young Edward’s coronation intended for 22 June, instead a sermon was preached outside St Paul’s Cathedral declaring the sons of Edward IV and his ‘whore’ illegitimate that “bastard slips shall not take deep root” and that Richard, Duke of Gloucester would be King. It was intended that Richard would then emerge to receive the acclamation of the people, but he was delayed and by the time he arrived the crowd had dispersed.

Richard III’s coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on 6 July 1483. Few could deny that he was now King, but they could question his right to be so – where were the Princes and if they were still alive why did he not produce them? The fact of his coronation could not conceal the fiction leading up to it nor the blood that had been shed in its pursuit. Had he murdered the princes so as to insert himself in the royal line of succession, many believed he had, that he had stolen the crown, and that he was a tyrant.

The paranoia that would come to dominate Richard’s thinking was not unfounded, he had made many enemies and now he saw them all around. When his former ally Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham was implicated in a plot against him Richard had him, hunted down and summarily executed. There wasn’t a nobleman in England who didn’t now fear for his life and many, among them previously loyal to the House of York now looked to Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian exiled in France as their saviour.

If Henry had any doubts regarding his right to seize the crown or in his ability to confront such a seasoned warrior as Richard on the field of battle his mother soon quashed them. She had worked her entire life for this moment and wasn’t about to let her son throw it away; with the money provided she purchase arms and ships. When he returned to his ancestral home it would not be as a supplicant but a prince at the head of an army.

Little wonder upon landing at Milford Haven then on 7 August 1485, Henry Tudor fell to his knees, clasped his hands together and looking to the heavens prayed, “Judge me O Lord, and favour my cause.” He would need his prayers for despite pledges of support the English nobility did not exactly rally to his cause but then neither would they to the King’s with any enthusiasm. Even so, when the two armies encountered one another at Bosworth Field in Leicestershire on 22 August 1485, Henry’s small force of 5,000 men would be outnumbered almost two-to-one.

Yet despite his numerical advantage it was Richard who was on edge. He did not trust the loyalty of his own troops while nearby looking on were the armies of Lord Thomas Stanley and his brother William. Once allies of the House of York their support could no longer be taken for granted especially as since 1472 Lord Thomas had been married to Margaret Beaufort and so was Henry’s stepfather. He had also rowed furiously with the King and so for now at least they would stand aside from the fray their presence a looming and very real menace.

Richard knew that the Stanley’s would not commit to his cause unless victory was assured but might to Henry’s regardless. On the eve of battle, he informed Lord Stanley that his son George was held hostage and that his life would become forfeit should he betray his King. Stanley refused to be intimidated replying, “I have other sons.” It did not augur well.

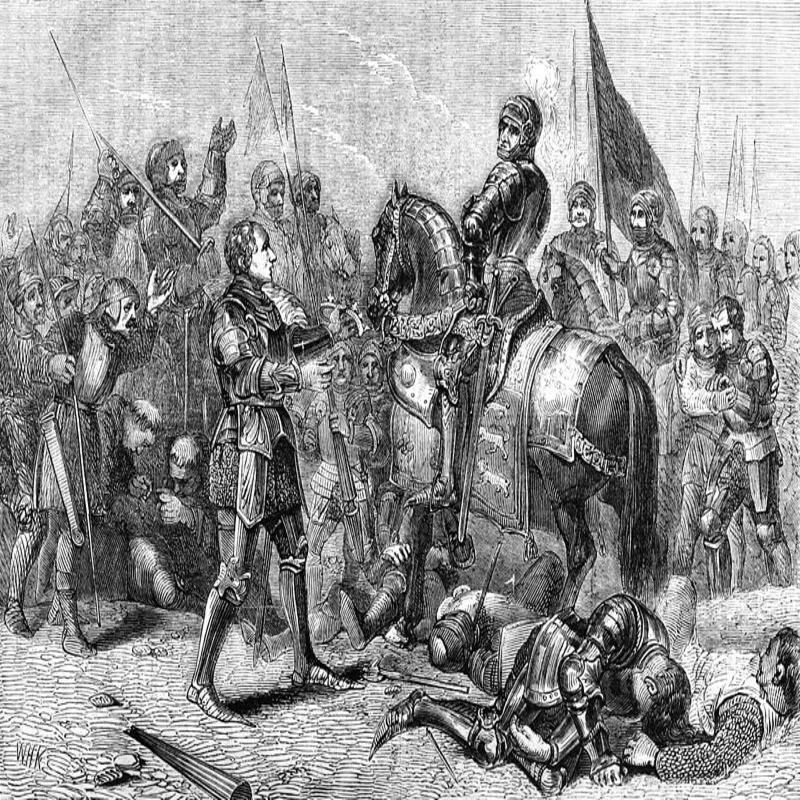

Fearing his army would not fight Richard decided to act; seeing Henry’s personal standard fluttering in the distance and accompanied by a small body of loyal knights he charged straight for it – if he could not defeat his army then he would kill the man they fought for.

It was a furious assault that cut a swath through the Lancastrian ranks but as Henry flinched and was hastened away from harm Richard could see Sir William Stanley’s army advancing against his own. It only served to spur him on but unhorsed and fighting alone he was eventually surrounded and brutally cut down; and there was to be no dignity in death for the late King, no courtesy of rank, no homage paid to his courage instead he was stripped naked, thrown onto a horse, and paraded through the streets of Leicester for all to see.

In the meantime, Lord Stanley finding the crown Richard had worn into battle hanging from a thorn bush presented it to Henry – a new dynasty had been born.

Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII at Westminster Abbey on 30 October ,1485, without opposition and to great acclaim but he knew that as long as the princes remained unaccounted for the question of legitimacy would dog his reign just as it had the man he’d deposed. He acted quickly to cement his position. First, he declared his reign to have begun on 21 August 1485, the day before the Battle of Bosworth making Richard the usurper and those who had supported and fought for him liable to the accusation of treason. Parliament agreed to this rewriting of history though not entirely without dissent. Also, to secure the support of those who might otherwise have opposed him he agreed to marry Edward IV’s youngest daughter Elizabeth thereby uniting the House of Lancaster with that of York and bringing to an end the dynastic war that had raged between them, or so it was hoped - hence, the emblem for the new regime of the White Rose of York emblazoned upon the larger Red Rose of Lancaster – the Tudor Rose.

Henry did what he could to legitimise his reign, but it had been a crown won by force of arms and he both feared and anticipated rebellion doing so for the rest of his life The visual acknowledgement of reconciliation aside however, Henry both feared and anticipated rebellion and would do so for the rest of his life. It fuelled a paranoia not unfounded that would prove wearying both on mind and body and the first of these rebellions would be swift in coming. Organised by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, a devoted servant to and loyal ally of Richard III who claimed he had been named the King’s successor in the event of his death it would have as its figurehead a boy, Lambert Simnel, who it was said was the son of Edward IV’s executed brother George, Duke of Clarence who with the Princes in the Tower presumed dead would be the closest surviving blood relative to the old King.

It wasn’t true of course and so despite a coronation of sorts taking place in Ireland the English nobility did not rally to his standard. Nonetheless, his army was a substantial and it took a series of prolonged and bitterly fought encounters before it was finally defeated at the Battle of Stoke Field on 16 June 1487, where the Earl of Lincoln was killed and Simnel captured.

Realising that Lambert Simnel was just a boy ignorant of the treasonable action he had undertaken Henry chose to be merciful and so rather than subject him to the gruesome fate that would normally await traitors he granted a full pardon and employed him in the Royal Household first as a lowly kitchen scullion and later as a falconer. He would survive well into the reign of Henry VIII.

In the meantime, the demonization of Richard III continued apace with Tudor propaganda portraying him as the murderer of the Princes in the Tower (though no bodies had been discovered) while depictions of him were distorted to stress his hunchback and physical deformity at a time when such things were thought a visible sign of evil, of the corruption of the soul, and the physical manifestation of God’s displeasure. Such propaganda would continue throughout the reign of the Tudor’s from Sir Thomas More’s seminal History of Richard III in 1513 to William Shakespeare’s eponymous play of the same name written in 1593. Henry VII was under no illusions as to the fluctuating nature of his grip on power and neither would be his successors.

A more serious threat to Henry’s reign and a sustained and prolonged one was that posed by Perkin Warbeck, a man about whom we know little other than that he later revealed himself. He claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, and it was said he had an uncanny resemblance to the younger of the missing Princes. He also had an explanation for his sudden re-appearance after ten years unheard and unseen. His brother, he said, had been murdered in the Tower on Richard’s orders but his life had been spared by those who had taken pity upon him for his youth and innocence and spirited him away to the Continent where he lived in seclusion under the protection of Sir Edward Brampton. Now he had come of age he as determined to seize what was rightfully his.

Perkin Warbeck it seemed was plausible and he quickly gathered support both in England and abroad. Henry was swift to act, those nobles he didn’t trust or was aware had expressed sympathy for Warbeck were arrested and put on trial for their lives. Many of the death penalties passed were later commuted to terms of imprisonment but not that of his Lord Chamberlain Sir William Stanley, the man who had come to his rescue at Bosworth, executed for treason.

Warbeck’s first attempt to land in England had to be aborted when meeting stiff local resistance at Deal in Kent his army were forced to flee back to their ships. Like Lambert Simnel before him he now sailed for Ireland where he could be assured a warmer welcome. Despite the initial enthusiasm however, he was unable to raise sufficient support to compensate for the losses incurred at Deal and so set sail once more, this time for Scotland.

It appeared that the Scots King James IV was prepared to provide Warbeck with all he required for an attack upon the Auld Enemy to the south, not just money and weapons but also an army. On 21 September 1496, their combined force with banners unfurled and to great fanfare crossed the River Tweed into England. They met little resistance but the people did not rally to Warbeck neither to the disappointment of James did his crossing the border prompt an invasion from France.

Upon learning an English Army blocked any further advance south and that another was approaching from the west James decided discretion was the better part of valour and retreated back cross the border. Abandoned by his Scots allies Warbeck sailed for Ireland once more where he laid siege to the town of Waterford without success.

Warbeck had twice been vanquished but Henry knew as long as he was loose he remained a threat and would return. He was right. On 7 September, 1497, Warbeck landed in England this time near Land’s End in Cornwall. Remote and far from London Cornwall has always had a unique sense of itself and it had never accepted Henry VII as its King having already once risen in revolt. Promising to alleviate the heavy burden of taxation levied upon them while also attending to their other grievances the people of Cornwall rallied to Warbeck and before a host of supporters on Bodmin Moor he was proclaimed King Richard IV of England.

With his small army reinforced by some 6,000 poorly armed and untrained Cornish volunteers Warbeck began his march on London but he was hesitant and progress was slow. Many unimpressed by his leadership began to abandon his cause and he had got no further east than Taunton where confronted by the army of Henry’s ally Baron Daubney and with his army already beginning to disintegrate he lost his nerve and fled to Beaulieu House in Hampshire where he hoped to find sanctuary. It wasn’t to be and taken prisoner he was sent to London in chains.

Henry VII evinced a leniency towards his enemies that would never have been countenanced by his predecessor and so it would prove with Perkin Warbeck who like Lambert Simnel before him would avoid any immediate assignation with the block while many of his supporters would have their death sentences commuted to terms of imprisonment upon the payment of a hefty fine.

Rather than face death Perkin Warbeck would be subject to interrogation first with a smile of sorts but then under duress, or at least the threat of it. It was enough to force a confession. He wasn’t the missing Prince after all, but an impostor, the son of a collector of taxes from the Flemish town of Tournai. His resemblance to the missing Duke of York, family connections, and ability to speak English brought him to the attention of Yorkist exiles at the Burgundian Court where the Duchess was the sister of Richard III. With her assistance and that of others at Court, Warbeck was able to embark upon his campaign for the English throne. His full and frank confession would spare Warbeck the fate of most traitors. Indeed, Henry appeared quite taken by the young man and not wishing to punish further for the sake of it he was released from the Tower of London, provided with rooms, and permitted to attend Court. But it was a partial freedom only. He was kept under constant guard, not allowed visitors, and locked in at night. Even so, it was remarkably lenient treatment for a man who had tried to violently seize the throne. It wasn’t enough for Warbeck however, who complained constantly of boredom and begged to be allowed to return to his wife in Tournai. When his request was refused, he tried to escape not once but twice. It sealed his fate - Perkin Warbeck was executed at Tyburn on 25 November 1499.

Henry VII’s reign may have been forged in the heat of battle but he was no warrior King, burning villages and territorial conquest had little interest for him but neither was he merely the dull accountant of historical imagination. Rather he was a shrewd politician and a sly man who knew that if his dynasty was to survive it had to govern according to the law and not by the sword alone. Its finances had to be sound, its taxes had to be fair, and it must take its place among the other great powers of Europe. These things he worked for tirelessly and though it didn’t always make for great history it laid the foundations for a century of remarkable achievement in all spheres of life under his family’s reign.

Determined his dynasty should last Henry governed through the Star Chamber which he used to circumvent the regular Law Courts to rule in his favour and the King’s Council, a body of his closest advisers who laboured on his behalf and were richly rewarded for doing so.

The men Henry appointed to his Council reflected his mind-set, they were not of the nobility as one might normally expect but for the most part men of lowly origin, merchants and tradesmen, the men who knew where the money was and how to get it. People like the grocer John Stille, Richard Empson the son of a sieve-maker, Edmund Dudley who had made his fortune in the wool trade and Richard Fox who had started his career as a schoolmaster. These were men the King could work with and they acted with impunity in the name of the law unimpeded by the law. The nobility who Henry so distrusted were less likely to serve on the King’s Council than they were to become its victim and Empson, Dudley and others who had no affection for their social betters were ruthless in their pursuit of the King’s desires as on often trumped up charges and under the threat of imprisonment or worse they squeezed every penny from those who could afford to pay.

In his inner-sanctum behind heavy oak doors locked and bolted with guards posted Henry Tudor really was the King in his counting house counting out his money as surrounded by clerks and accountants he admired the jewels, totted up the gold and weighed the silver while annotating the ledgers and auditing the books. In this way the wealth of England passed through his hands and there was barely a sovereign received or a penny spent that he was not aware of.

It was hardly surprising then that Henry’s character should divide opinion; the Italian diplomat and historian Polydore Vergil who was resident in London working as an agent of the Vatican met Henry on a number of occasions writing of him:

“His spirit was distinguished, wise and prudent; his mind was brave and resolute and even at moments of the greatest danger deserted him. He had a most pertinacious memory. Withal he was not devoid of scholarship. In government he was shrewd and prudent, so that no one dared to get the better of him through deceit or guile.”

He also provides us with a physical description:

“His body was slender but well-built and strong, his height above the average. His appearance was remarkably attractive, and his face was cheerful, especially when speaking, his eyes were small and blue, his teeth few, poor and blackish; his hair was thin and white; his complexion sallow”

But not all were as admiring, Sir Francis Bacon writing during the reign of Elizabeth referred to him as the ‘Dark Prince’ and thought him a duplicitous and ‘infinitely suspicious’ man while the visiting Spaniard Juan de Ayala was even more dismissive:

“He likes to be much spoken of and admired by the world, but he fails in this because he is not a great man. He spends all his time not in public but with his Council writing the accounts of his expenses with his own hand.”

Having spent so much of his early life in exile abroad Henry understood that for his dynasty to survive and prosper it had to reach out beyond the borders of England and take its place among the great Monarchies of Europe; to this effect he created an intricate network of envoys, spies, and paid informers who reported directly to the King who in turn would personally authorise any payments due. It was further proof of Henry’s grasp of politics, and it would reap its rewards.

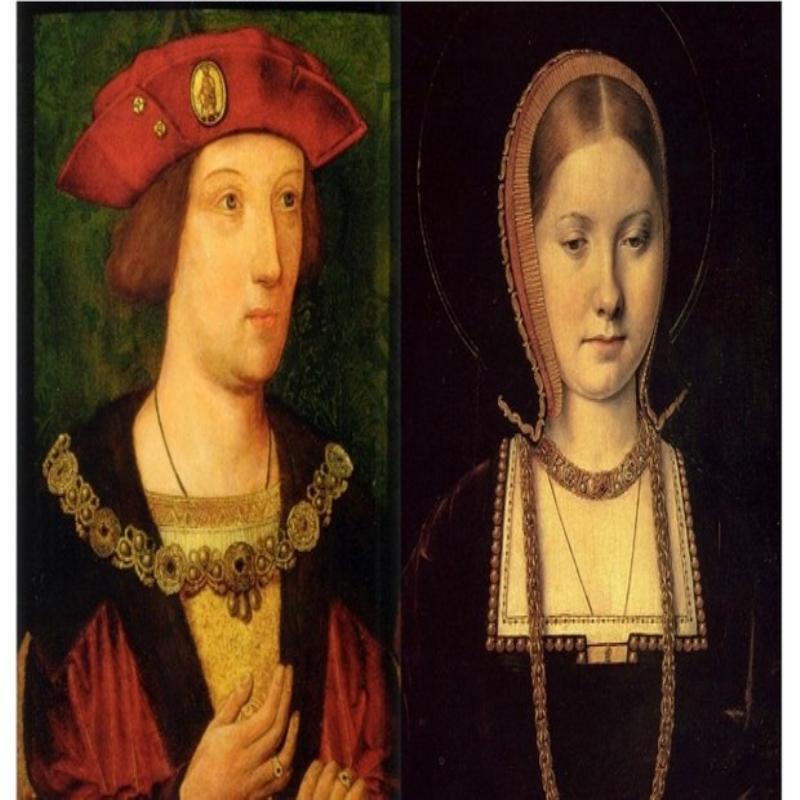

Since Spain’s unification under the joint rule of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile the Moors had been expelled from the south and much of the New World had been laid claim to. Even the successor to Saint Peter in Rome, Rodrigo Borgia, was a Spaniard. It was the emerging power in Europe and Henry was eager to take advantage. His eldest son, Arthur, named after England’s greatest Prince, was a vigorous, energetic and physically impressive youth in need of a bride and at the age of 11 he had been betrothed to Ferdinand and Isabella’s daughter Katherine two years his senior. Further complex negotiations would need to be undertaken before the marriage became a reality, but Henry was to prove as astute in foreign affairs as he was domestically.

Arthur and Katherine were married at St Paul’s Cathedral in London on 1 November 1501, in what was a diplomatic coup for Henry who at a single stroke had made England a player on the wider European scene. But his triumph would be short-lived. On 2 April 1502, after barely five months of marriage Arthur died of the sweating sickness. It came as a complete shock to everyone, and Henry was devastated; so much had been expected of the young Prince of Wales and now he was gone. Frantic negotiations began almost immediately to limit the damage. It was decided that the recently widowed Katherine should marry instead Arthur’s younger brother Henry, but a Papal dispensation would be required for her to do so based on the non-consummation of her original marriage. Katherine subjected herself to examination and declared under oath that she had never had sexual intercourse with Arthur. The dispensation was duly received, and all breathed a sigh of relief but the consequences which remained dormant for the time being would prove both significant and profound in the years to come.

Henry may have preserved the Spanish marriage, but his personal anguish was to continue. On 11 February 1503, his beloved wife Elizabeth died in childbirth aged just 37. By no means an affectionate man few realised how deeply the King had loved his Queen as for days on end he locked himself in his chambers refusing to see or speak to anyone other than his mother.

The final years of Henry’s reign were grim, he was lonely no doubt after his wife’s death and did consider re-marrying, but the inclination was forced and the desire fleeting; and he was ailing his face haggard and drawn, his body frail and stooped.

Juan de Ayala wrote:

“The King looks old for his years and young only for the sorrowful life he has led.”

He had achieved a great deal bringing peace and stability to England, a level of prosperity not known for years, a place at the table of European affairs, and established a dynasty that would survive the test of time but he had done so via a relentless process of threats and intimidation, by micro-managing the economy to a painful excess, and creating in England a form of police state that would become increasingly familiar throughout the years of Tudor rule to come - Henry VII’s reign had been a joyless one.

The first Tudor King died on 21 April 1509 aged 52, exhausted and physically depleted from years of tireless labour. His son Henry VIII was crowned with hope renewed and much enthusiasm, the old King was little mourned.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: