Hernan Cortes: Montezuma's Nightmare

Posted on 3rd March 2021

On 12 October 1492, Christopher Columbus planted the flag of Catholic Spain on an island he named San Salvador. He had inadvertently, for he thought he had made landfall in the East Indies, discovered the Americas – it was a New World.

Hernando Cortes de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano was born in Medellin in southern Spain sometime in 1485, the son of minor nobility who like many who are born to a little rather than no status at all always seeks more. He was in fact a distant relative (second cousin once removed) of the future conqueror of the Incas, Francisco Pizarro.

Described as a pale and sickly child noted for his petulance he was to grow into a haughty and arrogant young man who not willing to heed the advice of others chose not to follow in his father’s footsteps and become an Army Officer. He hoped instead to qualify as a lawyer, but he was not one to knuckle down to hard study however, and he was soon drawn to exciting tales of the New World across the seas where riches beckoned for the man audacious enough to seize them.

After spending two years in Salamanca training as a notary which at least provided him with a grounding in legal affairs he returned to Medellin having failed to gain entry to University much to the disappointment of his parents; but all he wanted to do was get to the New World and he was to spend much of the next year frequenting the ports of southern Spain hoping to find a ship willing to take him until at last, in the spring of 1504, aged nineteen, he embarked for the Americas.

Settling in Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola he was appointed notary for the town of Azua de Compostela and surprisingly perhaps was to prove an able administrator with an eye for detail who was quickly marked out for promotion, not that he had travelled so far to merely be an admired and respected bureaucrat. It was a frustrating time for the ambitious Cortes.

By 1514, he was serving as secretary to the Governor of the recently conquered New Spain, or Cuba, Diego Velazquez de Cuellar but relations between the two men was not good. Both were equally ambitious, and they eyed one another with suspicion. So, it came as somewhat of a surprise when n 1518 Velazquez provided Cortes with a charter permitting him to lead an expedition to first explore and then secure what he could of mainland Mexico for the King of Spain. Previous expeditions had achieved little, and it was possible that Velazquez simply wanted Cortes out of the way. If so, he soon changed his mind and cancelled the charter.

Cortes despite having to finance much of the expedition out of his own pocket was delighted at the opportunity, he had yet to secure his fortune and no less significantly his name back in Spain, here was his chance and he wasn’t about to squander it so when he learned that the charter had been revoked in February 1519, he sailed anyway.

His Armada was hardly an impressive one, 300 Spanish volunteers packed into 11 small vessels along with a similar number of Indian slaves and personal servants. What he hoped to achieve with such a meagre force he didn’t know but he did possess assets that went beyond mere numbers. Among his troops were 20 who bore firearms known as arquebusiers and 40 who were trained in the use of the crossbow. He also had 15 horses, a few small cannon and all the Spaniards wore steel helmets and breastplates - they were to prove significant.

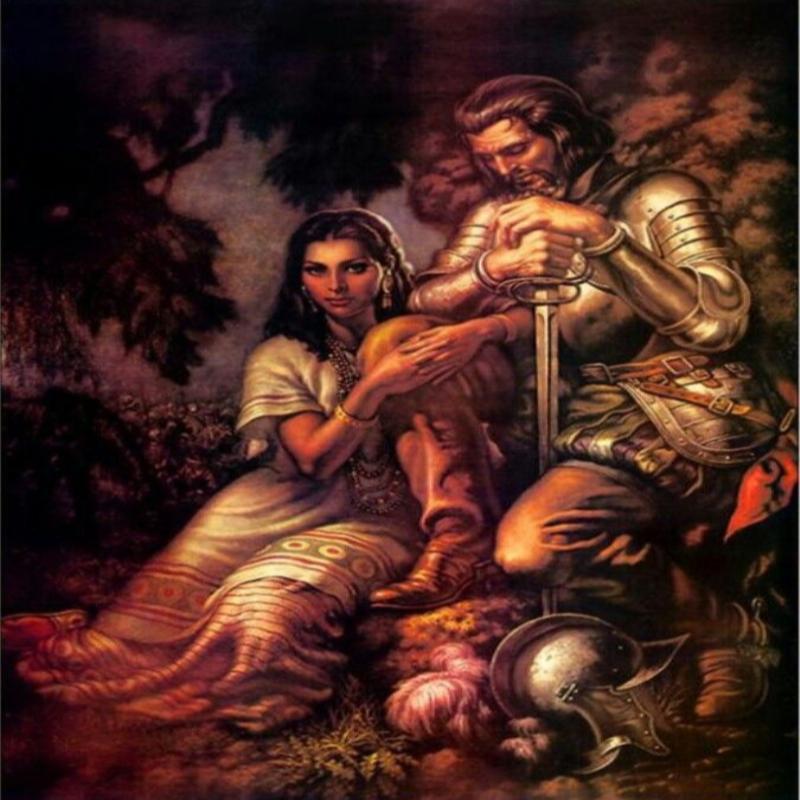

In March 1519, he landed on the Yucatan peninsula then in Mayan territory which he claimed for Spain before moving onto the River Tabasco where having dispersed the natives in a series of skirmishes he received a tribute of 20 female slaves among whom was Malinche who as Dona Maria would become both Cortes’s lover and bear him a son, more significantly she could speak both the Nahuatl and Mayan languages. As the Franciscan Friar Geronimo Aguilar could already speak Mayan, he would be able speak with Malinche, and through her Cortes would be able communicate with the Aztecs.

It was now that Cortes first learned of a great Empire further inland inhabited by a mighty and fierce people, the Aztecs; but Cortes sought one thing and one thing only, gold, and he barely spoke of anything else. His men were volunteers and they had not embarked upon this venture for the greater glory of God, they too sought their reward.

They sailed on north before mooring near modern day Vera Cruz, and it was here that they first encountered the Aztecs who had been monitoring them for some time.

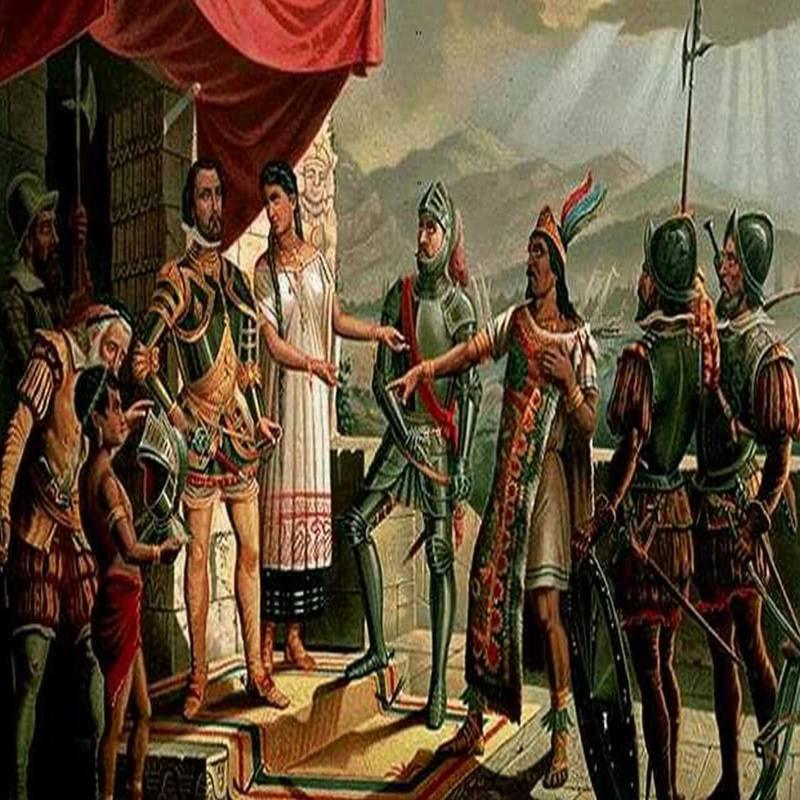

On Easter Saturday 1519, at San Juan de Ulua the Spanish camp was visited by Pitalpitoque and Tendile representatives of the Great Emperor Montezuma. They came at the head of a grand procession which impressed Cortes who was also a little dismayed that they were neither overawed nor surprised by his presence; but he was even more astonished by the gifts of gold they now presented him with.

He could barely contain his excitement while at the same time scrambling around trying to find a reciprocal gift for the Emperor. All he had were a few baubles and a red velvet cap. The meagreness of the offering was not well received and belied the suggestion that he represented a great King. But there was only one thing on Cortes’s mind. He asked the Ambassador: “Do you have more gold, because I and my men suffer from a disease of the heart that can only be cured by gold?” The Ambassador replied, “Yes, we do.” His words could not have been more inflammatory.

Cortes now determined upon a show of force and ordered his musketeers to fire into the air and his cavalry to ride at the gallop. The Aztecs shrank back and huddled together in fear and trepidation. They were astonished they had never seen anything like it before. The Aztec emissary ordered his artist to draw what he had seen and later reported back to Montezuma: “The strangers have sticks that spurt fire and ride deer as high as a house which snort and foam.”

Cortes was suspicious, uncertain as to why he and his motley crew had been treated with such honour and respect, but the reason would soon become clear.

It is possible that the Aztecs had been warned well in advance of the Spanish incursion but also prevalent was the legend of the God Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, who after being expelled from the land of Mexico had vowed to return from across the sea and reclaim his throne in this very same year according to the Aztec calendar. They were for a time at least thought to be Gods but they would soon prove themselves all too human.

Cortes’s requests to meet with Montezuma were ignored so he determined to continue inland and find this place of gold for himself but the tales told by natives of human sacrifice and that the Aztecs would flay the Spaniards alive, tear out their hearts and eat their flesh had unnerved his men. A mutiny was brewing and some of them expressed the desire to return home. Cortes did not debate the issue he had the ringleaders executed and then ordered the ships to be burned.

His men now had a stark choice, either follow him or die where they were. They chose the former.

In mid-August 1519, he began his march on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, but he would do so via a circuitous route so as to rally support from among the many indigenous tribes who both feared and detested the Aztecs including the Nahuas and Totonacs but the most formidable were the Tlaxcalans and with these the Spanish clashed violently. Indeed, for two weeks they had the Spaniards surrounded on a little hilltop and it seemed that Cortes and his small force might be wiped out, but the Tlaxcalans hated the Aztecs far more than they feared the strangers in their midst and Cortes was able to negotiate a peace that saw them cease to be an enemy and become instead his most invaluable ally.

In the early autumn Cortes resumed his march now reinforced by around 1,000 Tlaxcalan warriors. By the beginning of October he had reached the town of Cholula, the largest in Mexico after Tenochtitlan. Upon entering Cholula, Malinche warned Cortes that they were close allies of the Aztecs pointing out to him the altars of sacrifice and receptacles for body parts present in the town. Moreover, she had heard rumours that they intended to attack the Spanish possibly at night or after luring them into a trap.

Cortes decided to strike first and invited 100 of the town’s leading citizens to a meeting at which they presented themselves in all their finery, but the reception afforded them was not a friendly one. Upon their arrival they were surrounded by troops and Malinche told them they were guilty of treason against the Spanish King and must pay for it with their lives. Cortes then ordered their execution. The Spaniards then turned their weapons on the many people who had turned up to watch events killing around 2,000 men, women and children before ransacking the town.

Learning of the massacre at Cholula, Montezuma was heard to remark remarked, “My heart burns as if washed in chilli.”

Whether Cortes was ever seriously threatened in Cholula remains doubtful but if he had intended to send a message to Montezuma in Tenochtitlan then it had been a brutally effective one.

Cortes and his party arrived on the hills overlooking Tenochhtitlan on 8 November, no effort having been made to impede their passage and what emerged from the mist shrouding the valley below on that damp overcast morning left many of them awestruck. They had been told of the Aztec capital’s wonder, but few had believed it, now they could see it for themselves.

It was a city on a scale greater than any to be seen in Europe cast upon a lake that could only be traversed by three giant causeways; a stone metropolis of imposing structures, of pyramids, tall buildings, high walls, great steps and grand archways dominated at its centre by an imperious temple that reached up to the heavens as if imploring them to come closer. It was a city teeming with life, of commerce, market gardens, water borne craft - a quarter of a million people busy and productive. One Spaniard witnessing it for the first time wrote later:

“It seemed like an enchanted vision. Indeed, some of our soldiers asked whether it was not all a dream. It was so wonderful that I do not know how to describe this first glimpse of a thing never heard of, never seen of, or never dreamed of before.”

Even the hard-bitten Cortes, not a man inclined to wax lyrical other than about himself felt obliged to write:

"It was the most beautiful thing in the world; the most magnificent thing I ever saw."

But it was a city tainted by the stench of death, as Cortes was soon to discover.

The Tlaxcalans remained outside some distance from the city while guides led the Spaniards through its streets past a people intrigued but not cowed by their presence to a vast courtyard where Montezuma waited to greet them.

The Aztec Emperor was resplendent in the finest cloth, bejewelled and with a large entourage his advisers either side of him, servants swarming around; and he had come bearing gifts of gold, just small trinkets but enough to tease if not satisfy the lust of his guests.

But Montezuma was to be less imperious in speech than manner. Indeed, he spoke almost as a supplicant:

“O Lord, you have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your throne which I have briefly kept for you, but you are fatigued you are weary after your long journey. They said you would return and now you have done so, but first go to your palace and rest your limbs and go in peace.”

Cortes was surprised to be greeted so, he had claimed to be the representative of the great King across the sea, but it had been a bluff and he had nothing with which to prove it. Now this great man in this magnificent city, leader of a mighty Empire, was treating him as an equal maybe even his superior.

What was in Montezuma’s mind remains a mystery, perhaps he intended to lull the Spaniards into a false sense of security, perhaps he believed the words he spoke. Cortes soon became convinced that Montezuma believed him the God Quetzalcoatl and there may be an element of truth to this for the 8th of November in the Aztec calendar was the Day of Wind, the Day of Quetzalcoatl – but then it was also the Day of Deceit.

Writing many decades after of his experiences as a soldier in Cortes’s army Bernal Diaz del Castillo provides us with a description of the Aztec Emperor:

“The Great Montezuma was about forty years old of good height, well-proportioned, spare and slight, and not very dark, though of the usual Indian complexion. He did not wear his hair long but just over his ears, and he had a short black beard, well-shaped and thin. His face was rather long and cheerful, he had fine eyes, and in his appearance and manner could express geniality or, when necessary, a serious composure. He was very neat and clean, and took a bath every afternoon. He had many women as his mistresses, and he was quite free from sodomy.”

But as impressed as they were by Tenochtitlan the Spaniards had heard the tales of Aztec cruelty, they had seen the altars of sacrifice, the discarded human entrails, and it had filled them with a righteous fury that for all the grandeur these people were little better than Godless heathen savages.

Montezuma invited Cortes to see the Great Temple of the War God Huitzilopochtli upon the summit of which the hearts were torn from the bodies of those condemned to die as human sacrifice.

As Cortes and his party entered the dimly lit chamber the stench of death almost overwhelmed them for beneath the statue of the War God was a brazier of human hearts some still warm. The sight of it horrified them and Cortes tried hard to hide his disgust should it be mistaken for fear but even so turned to Montezuma wanting to know:

“I don’t understand how a prince as great as you could think that these are Gods, they are bad things called devils, and I would like your permission to place a Cross here and a picture of the Virgin Mary.”

A clearly offended Montezuma replied:

“Had I known you would insult our Gods I would not have brought you here, we hold these things to be good they bring us health, harvest, rain, and water. We must sacrifice to them. Do not mention this to me again.”

The idea that to keep the sun in its orbit and maintain the cycle of the seasons you must assist the Gods by providing them with heart and blood to function was difficult for a good Christian man to comprehend. Christ had given his blood and his life to redeem mankind these people kill others providing the blood to placate their Gods.

Whether or not human sacrifice in Aztec society was ever committed on the scale that has often been suggested it would serve as the justification for all of Cortes’s future actions.

A week after the events at the Great Temple Cortes arrived at Montezuma’s palace in the dead of night with an armed escort to inform him that he was now their prisoner and must return with them at once to their residence or be forced to do so.

Montezuma did not understand, he could not be made a prisoner, he was Emperor; and even if he did agree to become their captive his people would never tolerate it. The argument raged back and forth for many hours as Montezuma refused to accompany them and Cortes demanded that he do so, while all the time those Spaniards present became ever more anxious as dawn began to break. If what they were doing was discovered, they could all be massacred. Eventually, a Captain unsheathed his sword and angrily declared “Let’s kill him now and have done with it.”

Montezuma’s servants rushed to shield him, but Cortes chose not to intervene. It was only after Malinche translated the violence of the captain’s words that Montezuma reduced to tears, at last relented.

The Aztecs needed to be civilised Cortes had decided, an Empire as great as theirs could not be ruled by a man such as Montezuma, a pagan man. Neither could it any longer be denied to God. He would rule in the name of the King of Spain but with Montezuma at his side to provide his governance with the veneer of legitimacy.

It was no coincidence that the wealth of Tenochtitlan had not been delivered up to him as he expected and that no deal had been struck with Montezuma to do so. Cortes was impatient, more importantly so were his men. Orders were given for the palaces and temples of the city to be stripped of their treasures and for those who possessed gold to present it to their new masters. With their new wealth Cortes would create a Great Treasury to which only he had the key.

Meanwhile, in Cuba reports of Cortes’s success only further enraged its Governor Velazquez who remained determined to force his return and claim all the riches and the glory for himself. Cortes was no longer an ally but a rival, and so in April 1520 he despatched a force of 1,100 men to do just that under the command of Porfilo de Narvaez.

Cortes could not ignore the threat and would be forced to confront Narvaez even though he would be greatly outnumbered and reliant upon his Tlaxcalan allies for support. Desperate to intercept Narvaez before he reached the city Cortes left 200 men with Pedro de Alvarado in Tenochtitlan. It was a token force, and he would be dependent upon Montezuma to maintain order, but he had little choice.

When the two armies confronted one another however, it quickly became apparent there was little desire on either side for Spaniard to kill Spaniard except perhaps on the part of Porfilo de Narvaez whose reputation depended upon the outcome of any engagement.

On 27 May, after a brief skirmish during which Narvaez lost an eye, Cortes prevailed. Aware of the rumours that Mexico was a place of gold and great riches few of Narvaez’s men required much encouragement to now join with Cortes - as it turned out he would need every one of them for in his absence the situation in Tenochtitlan had taken a turn for the worse.

With his shock of red hair and handsome features Pedro de Alvarado was a difficult man to ignore and ebullient by nature and flamboyant of dress he was determined that no one should ever do so. But the image of the spirited cavalier belied a ruthless character and a cruel streak unrestrained by the desire for compassion.

On behalf of his subjects Montezuma approached Alvarado seeking permission to celebrate the Festival of Toxcatl which was granted under certain conditions - the people must gather in one place, and they must be unarmed.

On 22 May, some 600 of the richest men in Tenochtitlan accompanied by their families gathered in the confined space of the Patio of the Gods, a walled courtyard that was part of the Great Temple. Many were naked except for their feathered headdresses and necklaces of gold; others wore elaborate costumes colourful and bejewelled. But unnoticed by the celebrants Alvarado had blocked the exits and posted guards. No sooner had the festivities begun than troops entered the courtyard and opened fire. Panic ensued as with swords drawn the Spaniards cut and slashed their way through the thronging mass of people with those not cut down crushed in the desperate attempt to elude their assailants. According to one Aztec account:

“Some tried to escape, but the Spaniards murdered them at the gates while they laughed. Others climbed the walls, but they could not save themselves. Others entered the communal house, where they were safe for a time. Others lay down among the victims and pretended to be dead. But if they stood up again the Spaniards would see and kill them.”

Few escaped the bloodshed, and the Aztecs were to claim the attack had been unprovoked, the Spanish had been made mad by their lust for gold they said, something that Alvarado was to deny but Cortes’s well known parsimony and reluctance to share the contents of his treasury likely drove Alvarado to seize the opportunity of acquiring some wealth for himself.

News of the massacre in the Great Temple quickly spread and the Aztec people rose in fury against their oppressors. The call for warriors from far and wide was heeded as they gathered in great numbers to expel these cruel strangers from their land once and for all despite Montezuma’s repeated calls for calm and orders not to resist.

Alvarado had lost control of the situation and soon found himself besieged in the Imperial Palace.

On 29 June, in desperation he ordered Montezuma to address the mob gathered outside in person, but his commands were barely heard, his words lost among the banging of drums, blowing of horns, and howls of derision. The soldier Bernal Diaz del Castillo describes what happened next:

“Barely was the Emperor’s speech to his subjects finished when a shower of stones and darts descended. Our men who had been shielding Montezuma had temporarily neglected their duty when they saw the attack had ceased; but while he spoke to his Chiefs Montezuma was hit by three stones, one on the head, one on the arm, and one on the leg, and though we begged him to have his wounds dressed and eat some food and spoke very kindly to him, he refused. Then quite unexpectedly we were told he was dead.”

His description of the Spaniards reaction to Montezuma’s death may need to be taken with a pinch of salt, however: “Cortes and all of us Captains and soldiers wept for him, and there was no one among us who knew him who did not mourn him as if he was our father.”

But the suggestion that the Spanish killed Montezuma when they realised, he was no longer of any use to them also lends itself to scepticism. Why after all, murder a compliant Emperor only to have him replaced by whom exactly?

The following day Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan to find it in uproar. He demanded to know of Alvarado why the massacre in the Great Temple had occurred and was told they had been attacked after intervening to prevent a human sacrifice (the details of Montezuma’s death now seemed almost peripheral). But there was no time for recriminations for despite being greatly reinforced by the troops who had deserted Narvaez he knew they would be overwhelmed if they remained - he made the decision to abandon the city that very night.

The Spaniards heavy-handed and brutal approach had proven a grievous error and now they would pay the price. The Aztecs had blockaded the three causeways across the lake and so Cortes set his men to building a wooden bridge, a single, makeshift, rickety structure for over a thousand men, horses, wagons laden with baggage, and an artillery train.

Cortes believed the Aztecs would not fight at night and so they left as darkness began to fall their way lit by torches, their gold clutched close to their breast; but the Spaniards had barely begun to cross the bridge when the alarm was raised and the Aztecs descended upon them from all directions in their tens of thousands.

Stretched out in a long line exposed and vulnerable, stumbling around in the dark, terrified by the screams of their assailants and under a constant hail of missiles there could be no organised defence and many desperate to escape the mayhem plunged into the lake only to drown dragged to the bottom by the weight of their armour or were plucked from the water by Aztec warriors in their war canoes mutilated and killed; others were pulled to the ground beaten and stabbed to death; many more were captured alive and taken to the Great Temple where as the sun rose the following morning they had their stomachs opened, their entrails spilled, and their hearts torn from their chest and raised aloft in sacrifice to the War God Huitzilopochtli.

Few other than those in the vanguard of the column survived what was soon to become known as the ‘Night of Tears,’ barely 300 men. Some 870 Spaniards had been killed many only recently recruited. As the fortunate few gathered outside the city even the iron-willed Cortes was seen to weep, but not for long. He wished to know the whereabouts of the shipbuilder Martin Lopez – had he escaped? Upon learning that he had been wounded but lived, he said, “Then we go, for we lack nothing.”

The Aztecs celebrated their great victory believing the evil strangers had been vanquished forever, never to return. But by now they too were dying in their thousands from smallpox.

Cortes now made haste for the territory of the Tlaxcalans whom he prayed would still support him while being harassed every mile of the way by Aztec warriors their hit-and-run tactics playing havoc with the Spaniards already shredded nerves.

On 7 July, on the plain of Otumba, north-east of Tenochtitlan, Cortes was confronted by an Aztec Army many times the size of his own. This was their opportunity to kill all the remaining Spaniards and have done with the affair, but they seemed more interested in mocking them for their previous humiliation than engaging them in battle. Cortes seized the initiative and attacked targeting the Aztec General for an early death and with their leader killed the Aztec army disintegrated and fled. Cortes had lost a further 70 men he could ill-afford but his rout of the Aztec Army convinced the Tlaxcalans that he was still the man able to defeat their mortal enemy.

Astonishingly within a year Cortes would once again stand before the walls of Tenochtitlan for whatever he may have lacked in tactics and tact he more than made up for in resolution and the iron determination to succeed.

In the forests of Tlaxcala under the supervision of the shipbuilder Martin Lopez the Spaniards constructed a fleet of 13 prefabricated Brigantines that would be transported on the backs of more than 8,000 native porters to Tenochtitlan where pieced together they would control the lake, cut-off the water supply and starve the city into submission.

While Cortes was preparing his unanticipated return to the Aztec capital life in Tenochtitlan was returning to something like normal despite the ravages of those European diseases against which they had no immunity one of whose victims was Cuitlahuac who had succeeded his older brother Montezuma as Emperor. He may have presided over the expulsion of the hated strangers, but he would be dead of smallpox within three months.

The Aztec nobility chose Cuauhtemoc, a man who would fight as their new Emperor. He had promised to do so and would prove as good as his word.

By late May 1521, Cortes once more stood before Tenochtitlan with his ships and a formidable army, 80,000 Tlaxcalan and other native warriors reinforced by Spanish troops from Cuba who had heeded his call for volunteers. He expected a swift victory but had prepared for a long siege if required; with the city surrounded and his ships dominating the lake and controlling the means of access to the city he had Tenochtitlan in a vice-like grip and was determined not to let go.

The Aztecs were not accustomed to siege warfare, but they adapted soon enough. The causeways they protected with barricades and traps laid for the unwary while sharpened stakes and nets were placed beneath the waters of the lake to impale and snag the light craft with which Cortes hoped to land troops on the shore. Aztec warriors also no longer fled at the sight of horses or cowed at the sound of guns though the giant Mastiffs trained to kill still struck terror into their hearts. Neither did they believe any longer that the Spaniards were divine or invincible - they bled, they died, and they feared just like everyone else. Indeed, Spaniards were being regularly killed and those who fell into their hands they sacrificed upon the altar of the Great Temple in broad daylight for all to see.

Once again Bernal Diaz del Castillo leaves us a description:

“The dismal drum sounded again as we saw our comrades who had been captured dragged up the steps of the Great Temple to be sacrificed, cutting open their chests and drawing out their palpitating hearts to be offered to their idols – the Indian butchers.”

Cortes’s attempts to storm the causeways were repulsed time and again while his ships were being harassed by Aztec war canoes. Even their camps outside of the city had been attacked. The Aztecs had also taken to distributing the body parts of dismembered Spanish captives among the camps of their Tlaxcalan and other allies. It proved very effective propaganda and many now began to believe the Aztec prophecy that the strangers would be annihilated and so no longer believing in the Spaniards capacity to defeat the mighty Aztec Empire their native allies abandoned the siege in their droves until by late June only a few remained. Cortes could not abandon the siege however, so he would bombard the city from his Brigantines, but the attacks would cease, attrition would have to do its work. He told his men, “The Aztecs will eat up all the provisions they have soon enough.”

But the Spaniards were making little headway with the city’s defences still largely intact, but it could no longer be re-supplied and the people were starving. The more desperate the situation the greater the number of people needed to be sacrificed to propitiate the Gods. If prisoners were not available, then children would suffice.

Malnourished and weakened by disease the Aztecs were in no position to exploit Cortes’s predicament and in time his native allies would return encouraged to do so by the promise of rich reward, and in the case of the Tlaxcalans the desire for revenge after years of brutal oppression.

The failure of Cuauhtemoc to break the siege even after Cortes had been deserted by his native allies did not indicate a lack of desire on his part but of his powerlessness to do so for the situation in Tenochtitlan was dire. As many as 40% of the population had already died of disease, the water supply was scarce and tainted, food was at a premium, and he was running short of warriors.

Cortes sensed the time had come to end things and ordered his army to advance upon the city in three separate columns before linking up to descend upon the Great Temple and the Emperor’s Palace. But it would prove far from easy as all took up arms to defend hearth and home – ambushes were laid, missiles rained down from rooftops, prayers and imprecations rent the air while the human sacrifices multiplied two-fold, three-fold and even more as the struggle for every house, every street continued fierce and remorseless. So bloody was the fighting that despite the inevitability of the outcome Cortes remained willing to negotiate the surrender of the city to bring it to an end but Cuauhtemoc would not countenance it.

It had been a desperate last stand but finally after a week of almost continuous warfare and close-quarter combat Aztec resistance crumbled and those who could began to flee across the lake and into the interior.

On 13 August, Cuauhtemoc’s flotilla of small boats carrying himself and his family was intercepted, and he was taken captive – the siege was over.

Taken before Cortes the Aztec Emperor remained defiant calling upon the Spaniard to take his dagger and strike him dead. But Cortes refused telling him: “You have defended your city like a brave warrior and a Spaniard knows how to respect valour, even in an enemy.”

His magnanimity was to prove short-lived however, as eager to retrieve the treasure lost during the ‘Night of Tears’ he put Cuauhtemoc to the torture to reveal its whereabouts. He denied any knowledge of its whereabouts but after having his feet held over hot coals and doused in burning oil, he told him it had all been thrown into the lake.

Like many victims of torture, it seems Cuauhtemoc merely told the Spaniards what they wanted to hear for very little of the gold and precious jewels were ever recovered.

Cortes chose to retain Cuauhtemoc as Emperor in part to keep order but also to assist in bringing in the gold that continued to obsess him. Meanwhile in Tenochtitlan the murder and rapine continued for some time with the Tlaxcalans particularly merciless in their pursuit of vengeance. Indeed, so bad was it that reports of the brutality reached the Royal Court in Spain and Cortes was forced to plead his innocence in a letter to the King blaming the violence on his Native Indian allies and insisting that he had done all he could to prevent it.

Cortes was to govern, Cuauhtemoc was to reign, but it was an uneasy partnership. Cortes doubted the Aztec Emperor had ever reconciled himself to Spanish domination and he remained the only man who by reputation alone could still challenge that domination, even if by now the Aztecs were a broken people. In early 1525, Cortes ordered Cuauhtemoc to accompany him on an expedition to Honduras in what was likely a ruse to lure him away from the city in order to kill him.

On 27 February, in front of witnesses Cortes accused Cuauhtemoc of plotting to assassinate him. He denied the charge but at a hastily convened trial was found guilty and sentenced to death. At his execution he declared that he was being unjustly killed and that Cortes would have to answer before his God for what he had done - it made no difference.

For all the blood that had been shed in the preceding years it was felt that Cortes had overstepped the mark in his execution of Cuauhtemoc who had admirers even among the Spanish many of whom believed the charges had been fabricated. They were after all, Conquerors, Conquistadores, they did not have to behave this way.

Cortes was to remain in Mexico to build a new city in the Spanish style upon the ruins of Tenochtitlan, but his power waned as he became the titular head of an Administration increasingly run by bureaucrats sent from Madrid. Still, he was a very wealthy man though more from his ownership of silver mines rather than his anticipated procurement of gold in vast quantities. A fortune he had accrued, it was said, by not distributing the wealth of the Aztecs among his men as he had promised, which was largely true. Not that he was willing to own up to it instead believing that all the accusations made against him including those of venality and cruelty were merely attempts to undermine him. He declared in a letter to the King that were it not for him Mexico would not be a part of the expanding Spanish Empire at all, which was also true, though it did not endear him to his opponents. He was not receiving the credit he deserved and even though he was honoured time and again it was never enough. He was to write many times to Charles V complaining of the meddling from Madrid and the overweening power of the Church, even attending the Royal Court in person to plead his case for greater freedom of action and where, much to his irritation he failed to be recognised.

As far as Charles V was concerned it mattered not, Mexico belonged to Spain and to God, not Cortes. Then again what honours are sufficient for a man who has destroyed a civilisation, especially when it takes so many to build a New World.

Hernan Cortes died in Spain on 2 December 1547 aged 62, a very rich but disgruntled man.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: