Inferno: The Great Fire of London

Posted on 18th February 2022

The Great Fire that engulfed so much of London began at the bakery of Thomas Farriner in Pudding Lane just after midnight on September 2, 1666. It is unknown exactly how the fire began and Farriner was in no position to find out having been forced to flee along with his daughter by jumping from an upstairs window. His maid who refused to do likewise perished in the flames.

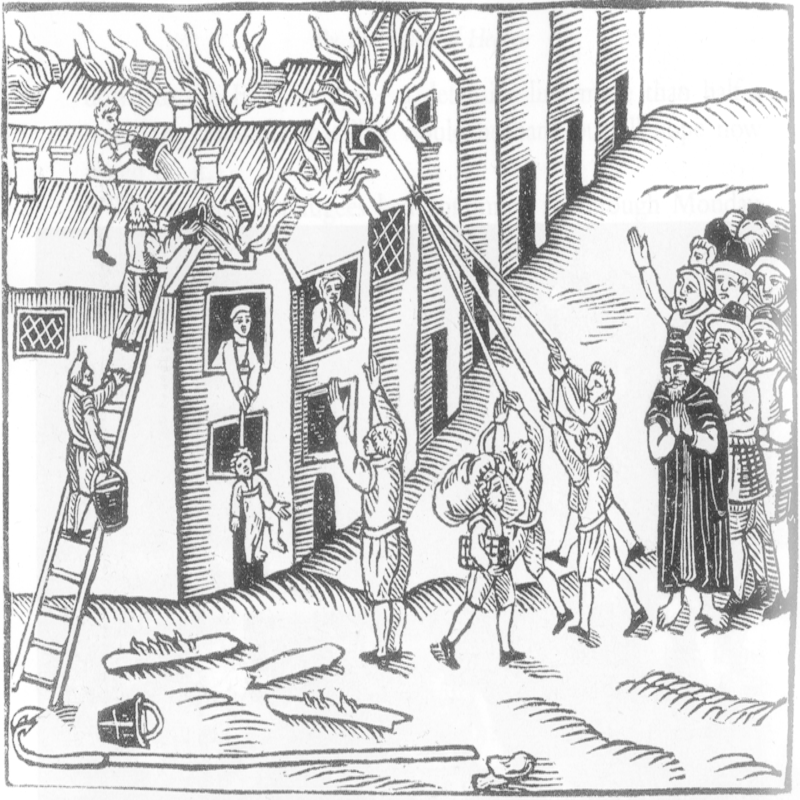

Despite the severity of the blaze little was thought of it at the time. Fires amid the narrow streets and timber framed houses of the Old City were commonplace and most petered out of their own accord having perhaps consumed one two neighbouring homes. But this was different, a strong westerly wind on what had been a particularly hot and dry summer fanned the flames and caused the fire to spread with great rapidity. So much so in fact, it was thought necessary to call upon the Lord Mayor Thomas Bloodworth at home and waken him from his slumbers. He complained bitterly at the inconvenience but nonetheless rose, dressed and visited the scene to see for himself – he did not remain long.

Everything was frantic, people were running hither and thither but then firefighting in the city was rudimentary and to say the least labour intensive; water had to be drawn from the River Thames using primitive pumps or more likely carried by bucket or passed from hand-to-hand along lines of people. But this was unlikely to have much impact upon a fire of such intensity. More effective was the use of hooks to tear down nearby buildings and deny the fire the means of spreading further. But this entailed the wilful destruction of property and the lawsuits that would invariably follow. When permission was asked of the Mayor to do so he refused remarking, “Pish, a woman could piss it out.” He then returned home and went back to bed. It soon became apparent however, that this was more than just another fire and as its flames lit up the London skyline Samuel Pepys noted in his diary:

(Lord’s Day) “Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today; Jane called us up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the city. So I rose and slipped on my night gown, and went to her window and thought it to be on the backside of Mark Lane at the farthest; but being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off and so went back to bed and asleep.”

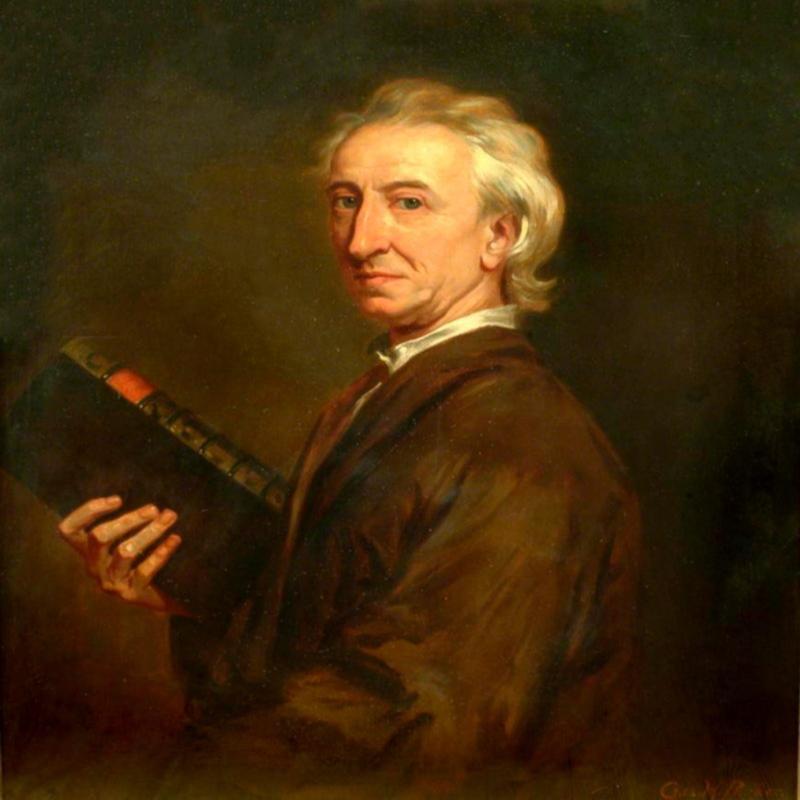

Pepys fellow diarist John Evelyn who had long considered the overcrowded streets of London as a catastrophe waiting to happen saw events in a very different light:

“This fatal night about ten, began that deplorable fire, near Fish Street in London. I had pub, prayers at home. After dinner the fire continuing, with my wife and son took coach and went to the bank side in Southwark, where we beheld that dismal spectacle, the whole city in dreadful flames near the waterside, and had now consumed all the houses from the bridge all Thames Street and upwards towards Cheapside, down to the three cranes and so returned exceedingly astonished, what would become of the rest.”

Any semblance of complacency was soon abandoned and King Charles II informed of the situation was quick to respond. He sent for Pepys who in his capacity as a leading Civil Servant at the Admiralty was ordered by the King to tell Mayor Bloodworth to spare no houses in the fires immediate path. On his journey what met his eyes astonished him:

“Every creature coming away laden with goods to save, and here and there people carried away in beds. Extraordinary goods carried away in carts and on backs. At last met my Lord Mayor in Canning Street, like a man spent, with a handkerchief around his neck. To the King’s message he cried, ‘Lord! What can I do? I am spent, people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses; but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.”

Having delivered his message Pepys, leaving the Mayor in a state of some distress, returned home past houses, “so very thick thereabouts and full of matter for burning, as pitch and tar, and warehouses of oil, and wine, and brandy, and other things.”

It was time for Mr Pepys to look to himself. Having earlier witnessed his friend Sir William Batten dig a pit in his garden to keep safe his valuables he determined to do the same, “In the evening Sir William Penn and I did dig another and put our wine in it; and I my parmesan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.”

Both the King and his brother James, Duke of York were present at the scene not only taking command of the fire-fighting effort but helping physically to douse the flames. The King even distributed coin to those who had lost their homes and were in obvious distress. John Evelyn was full of praise:

“It is not indeed imaginable how extraordinary the vigilance and the activity of the King and Duke was, even labouring in person, and being present, to command, order, and reward, and encourage workmen; by which he showed his affection, to his people, and gained theirs.”

Despite their best efforts the fire continued to rage and spread faster than the houses in its path could be pulled down. As a result, dangerous though it was to do so, the King ordered the garrison of the Tower of London to use gunpowder to blow up rows of houses and create effective firebreaks before the blaze which had already destroyed St Paul’s Cathedral crossed the Thames and threatened the palaces and homes of the nobility and wealthier class.

This did indeed help to slow the spread of the fire, but it did not end it entirely, only nature could do that, and it wasn’t until the wind dropped late Tuesday night that the fire fighters at last had the opportunity for their valiant efforts to take effect. The fire continued to rage but it had ceased to threaten.

By Friday September 7, the fire had all but petered out and people were able to see beyond the smoke the scarred landscape it had left behind. John Evelyn wrote:

“I went this morning on foot from Whitehall as far as London Bridge, through the late Fleet Street, Ludgate Hill by St Paul’s, Cheapside, Exchange, Bishopsgate, Aldersgate, and out to Morefields thence through Cornhill and with extraordinary difficulty, clambering over yet mountains of smoking rubbish, and frequently mistaking where I was, the ground under my feet so hot, as made me not only sweat but even burnt the soles of my shoes.”

Samuel Pepys likewise noted in his diary:

“Up by five o’clock; and blessed be God! Find all well, and by water to Paul’s Wharf. Walked thence, and saw, all the town burned, and a miserable sight of Paul’s Church; with all the roofs fallen, and the body of the quire fallen.”.

The Great Fire raged uncontrolled for five days and had razed to the ground most of the old medieval city of London. Its Roman Walls were no more, 13,500 houses were destroyed as also were 87 parish churches, 44 company halls, numerous warehouses, the Guildhall, the Customs House, the Royal Exchange, Bridewell Palace and of course St Paul’s Cathedral. There were thought to be only six fatalities though many deaths in the poorer area may have gone unrecorded and some 200,000 were left homeless.

For some however, the aftermath of the Great Fire would be worse than the conflagration itself. Following so close on the heels of the Great Plague the previous year which had killed 80,000 of London’s inhabitants few believed such a calamitous fire could have been the result of an accident. For those of a superstitious or religious mindset the year was 1(666) the number of the beast and fire could only be God’s judgement on a city steeped in sin. For others the fire had been started deliberately as part of a Catholic Plot, and anti-Catholic hysteria was never far from the surface in Stuart England.

For weeks after the fire those of a foreign appearance who spoke with an accent or were of swarthy complexion were in danger of being attacked in the street and several Dutch and Huguenot merchants were murdered and it is possible more were killed in this manner than perished in the fire itself.

Not all went along with the notion of a Catholic conspiracy, the London Gazette wrote: “Notwithstanding which suspicion, the manner of the burning all along in a train, and so blown forward in all its way by strong winds, make us conclude the whole was an effect of an unhappy chance, or to speak better, the heavy hand of God upon us for our sins.”

Even so a French watchmaker Robert Hubert would confess to starting the fire deliberately by throwing a smoking grenade through the downstairs window of the bakery even though it had no downstairs windows. He would in fact change his story repeatedly and appeared merely to say what his interrogators wanted to hear. Thomas Farriner who denied any responsibility for what occurred would sign the Bill that accused Hubert of arson.

Hubert’s confession that he was an agent of the Pope fitted well the conspiracy theories then circulating and after a brief trial he was hanged at Tyburn on 29 October. The Captain of the Maid of Stockholm would later declare that Hubert was still aboard his ship crossing the North Sea two days after the fire had started. His written statement did no more to help the unfortunate watchmaker than his death did to assuage the anger of the mob. Fearing the violence would escalate the King issued a proclamation forbidding people to “disquiet themselves with rumours of tumults” and instead look to charity for the victims.

Once the furore over the cause of the fire died down so the rebuilding of London could begin, and various plans were suggested for its redevelopment including those put forward by Sir Christopher Wren, Sir Robert Hooke, and John Evelyn himself. All were rejected and over the next decade it was rebuilt much as it had been before except for the fact that wood was banned as a building material and safety became a consideration in construction for the first time.

Sir Christopher Wren would of course design the new St Paul’s Cathedral though not as he had originally intended but which along with the 51 other destroyed Churches, he rebuilt would go a long way to reviving a city which though scarred and traumatised would go on to prosper as never before.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: