John Brown: The Taper Light of Freedom

Posted on 1st August 2021

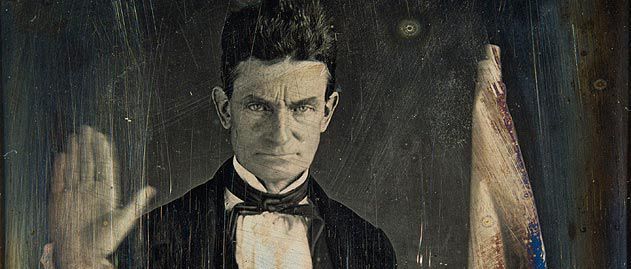

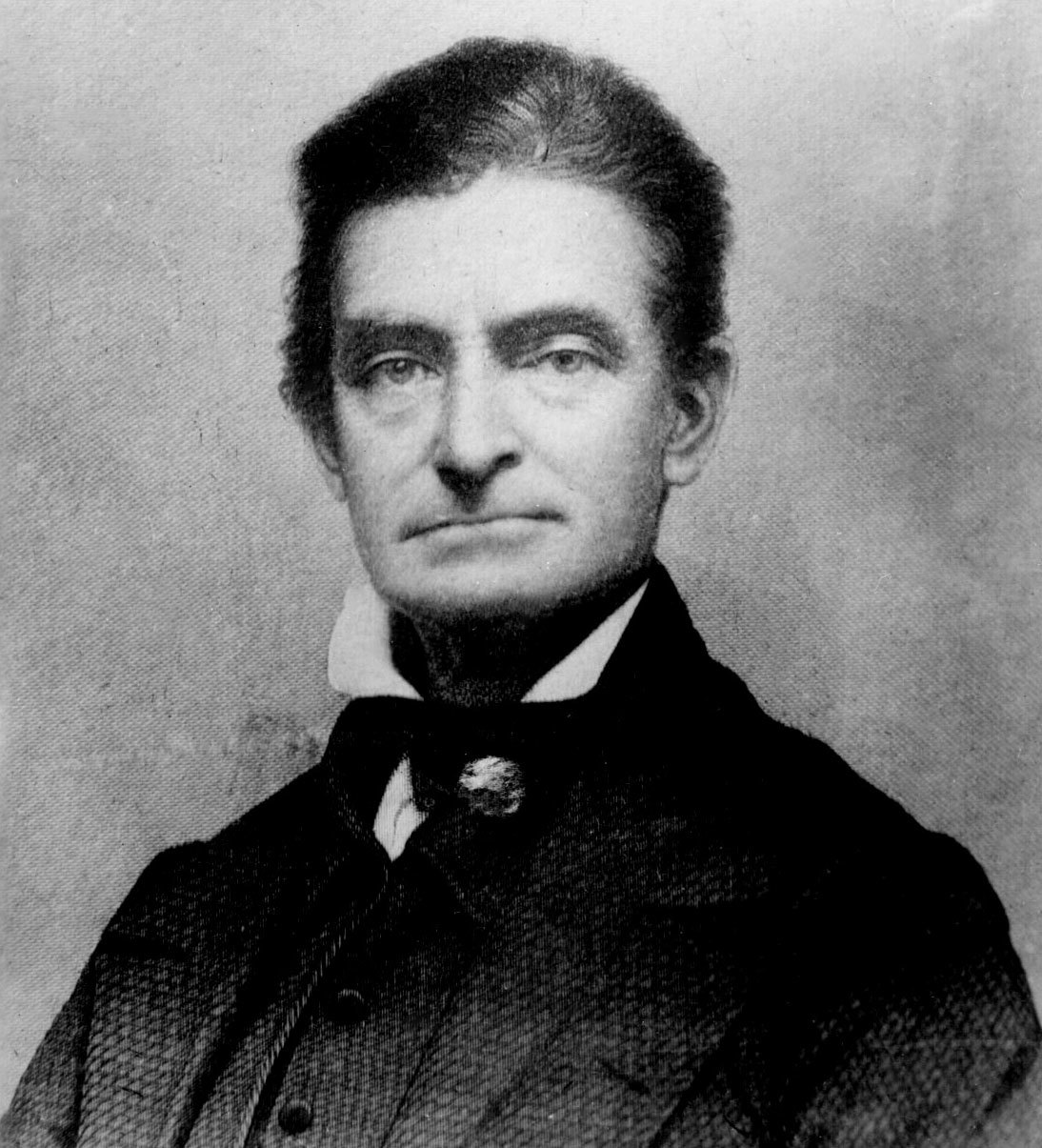

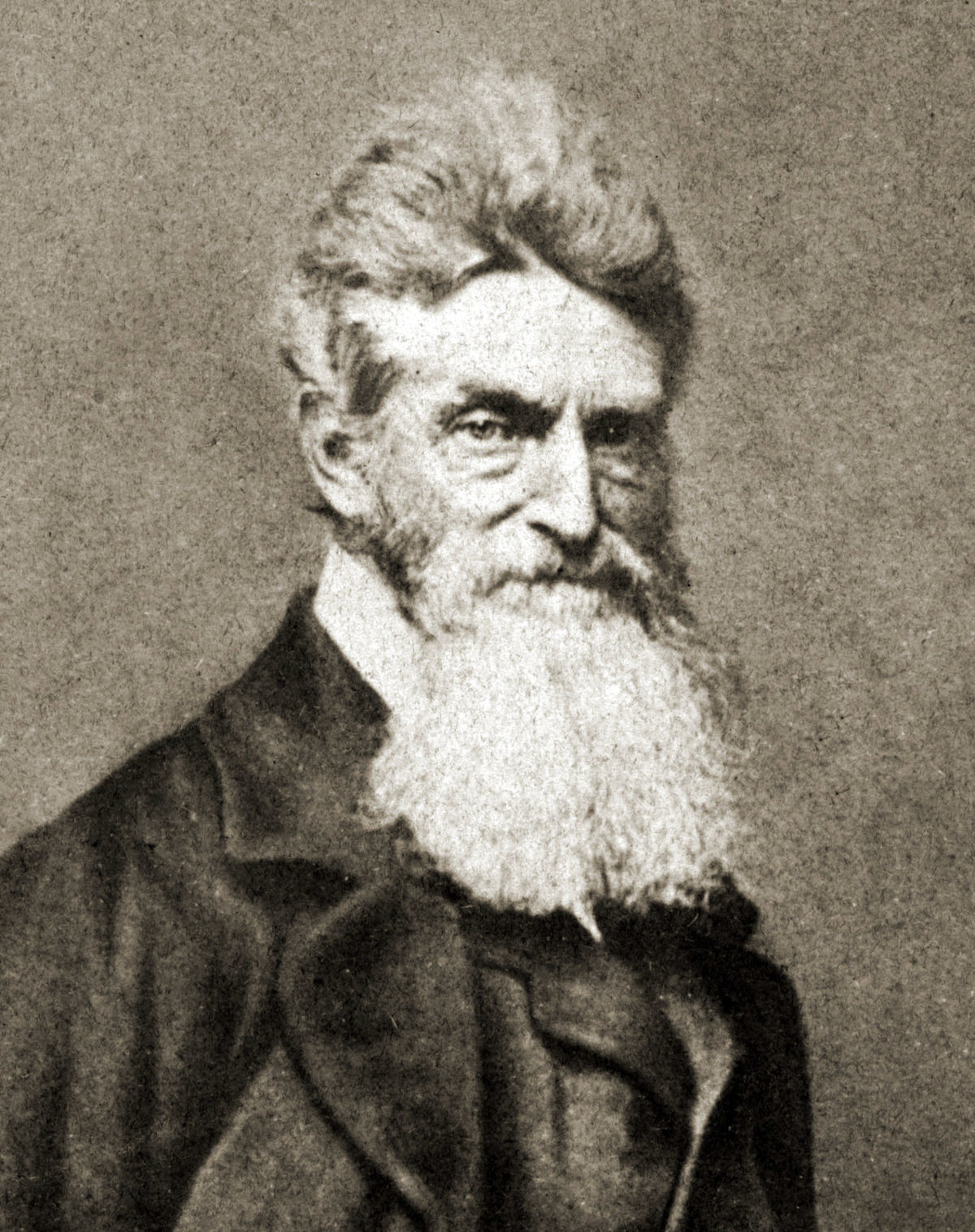

There are few more controversial figures in American history than John Brown to some he was on the side of the angels, a spiritual man, an anti-slavery man and a hero; to others he was a religious fanatic, a traitor and a cold-blooded killer.

John Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut on 9 May 1800, the fourth of eight children, but soon after his birth the family moved to the town of Hudson, Ohio.

The young John was in awe of his father who ran a flourishing tannery business and was to spend much of his life trying to emulate his success, but his many business ventures were to end in failure leaving him heavily in debt for the rest of his life. Raised a strict Calvinist and for a time a member of the Congregationalist Church he sought solace in religion seeing his failure as God's Judgement upon him and the more he failed the more deeply religious he became.

At the age of sixteen he left home and moved to Plainfield, Massachusetts and for the next twenty years moved regularly from town to town during which he married twice, fathered twenty children and failed in business again and again. He may have been busy but if his life was not working out as he hoped it would but then he had not yet found a cause.

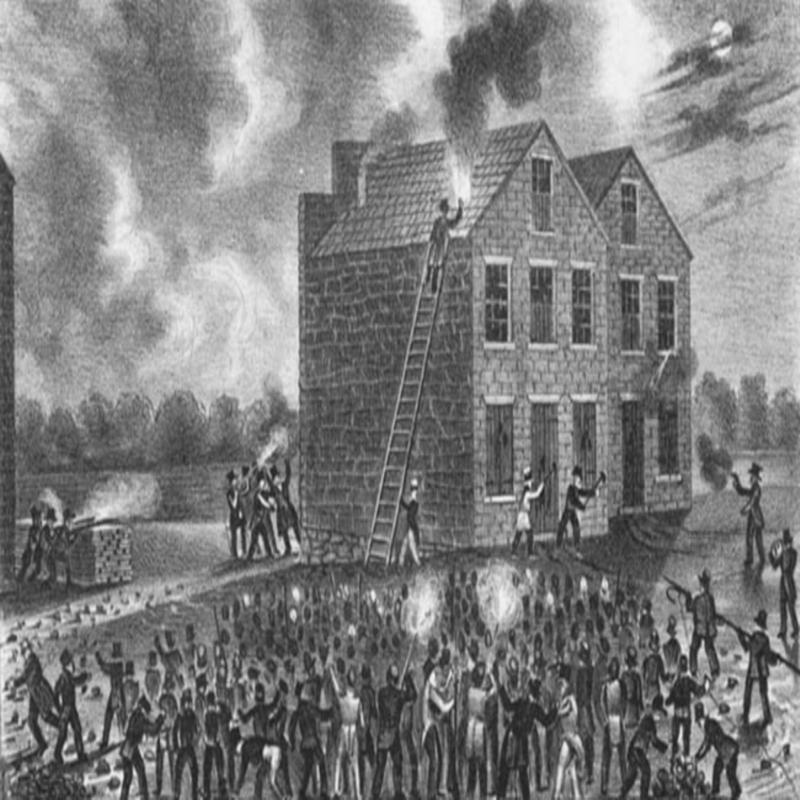

In 1837, a mob attacked and destroyed the printing presses of the vocal anti-slavery campaigner and Editor of an abolitionist newspaper, Elijah P Lovejoy before dragging him from his home and shooting him dead. It was the first time that a white man had been murdered by other white men over the issue of black slavery.

John Brown considered Lovejoy a martyr, a man who had given his life for a noble and Godly cause. At a Church meeting he vowed: "Here, before God, and in the presence of these witnesses, I, John Brown, consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery". He had at last found a purpose to his life but for the time being he was busy trying to sort out his own which was in turmoil.

In 1842, he was declared bankrupt, and the following year four of his children died of dysentery. It was a desperate and distressing time, but every death endured, every tragedy encountered merely appeared to deepen his religious conviction and his belief that God had chosen for him a special purpose.

Constantly on the move, partially as a result of trying to avoid his creditors, in 1846 he went into business with an associate Simon Perkins as a wool commissioner. Unable to contribute much financially to the business his main input was to be his expertise, but he tended to side with the small farmers against the larger corporations with whom he was supposed to be doing business and this natural inclination to favour the less well-off undermined his best endeavours as a commissioner. Having managed to alienate the manufacturers he was supposed to be representing the business went bust in 1849 owing a considerable amount of money, most of the burden for which was carried by Perkins. Brown left town soon after leaving no forwarding address.

He now found himself in the town of North Elba in New York State where he was struggled to make ends meet with such a large family to support. Even so, upon hearing the news that trouble had broken out between pro and anti-slavers in Kansas he decided to give up business altogether and instead devote himself to the abolitionist cause.

It had not yet been decided whether Kansas should be a Slave State or not and so in the hope of achieving a fait accompli The Free-Soil Movement provided grants for abolitionist families who wished to settle in the State. In response, pro-slavery Border Ruffians mostly from the neighbouring State of Missouri determined to prevent them from doing so. An effective war had broken out in Kansas.

Such was the anger on both sides that violence even reached the floor of the Senate House in Washington when Southern Senator Preston Brooks beat abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner senseless with his cane.

Brown believing that violence had to be met with violence moved to Kansas to join with the Free State settlers and fearing for the safety of his family as a result he was determined to take the war to the enemy. He formed what was in effect a Murder Squad whose only aim was to seek out and kill every known pro-slavery man in Kansas. Their deaths, he said, would stand as an example to others.

At 10.00pm on 24 May 1856, at Pottawotamie Creek his gang took five pro-slavery men from their homes and cold bloodedly hacked them to death with axes and broadswords in front of their distraught families. Brown was later to claim that he was not present at Potawatomie Creek and had not participated in the killings but there seems little doubt that he would have approved of and ordered it.

The violence in Kansas continued to increase as more and more pro-slavery men from Missouri invaded the State. The abolitionist town of Lawrence was raided and pillaged while Brown's new homestead was burned to the ground and his son Frederick shot and killed. He would not be cowed however., and on 2 June 1856 successfully defended the town of Palmyra against attack while on 30 August, he lost a battle at Osawatomie against vastly superior forces but only after inflicting heavy casualties.

The violence was escalating all the time and by September more than 3,000 Border Ruffians from Missouri were active in Kansas. Brown was willing to face them all and was preparing for a final showdown when the new Governor John W Geary managed to impose a fragile peace.

The peace held, but only just. It made no difference to Brown either way, he was by now fully committed to the struggle against slavery which he considered to be his Mission from God. If the struggle was not to take place in Kansas, then he would go elsewhere.

In anti-slavery circles in the North, he was already being hailed as a hero but this was never enough for Brown, he didn't just want to oppose slavery he wanted to be the man responsible for ending it. The best way he thought of doing so was to incite slave insurrection in the South. If he could spark an incident, he was confident that the slaves would rise up and throw off their shackles for themselves.

Following the imposition of peace in "Bleeding Kansas" Brown travelled east to solicit funds for his new project and whilst in Washington he was introduced to some of the most prominent abolitionists in the country including Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison and writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and David Thoreau. He was warmly received, but his plan for a slave insurrection less so.

Brown's proposal was for a raid on the Federal Armoury at Harper's Ferry in West Virginia, but as knowledge of his plan spread the funds dried up and many of his erstwhile supporters began to desert him. Indeed, Frederick Douglas used his influence within the black community to dissuade people from enlisting in the mad-cap plan. As a result, Brown who had been hoping to raise a fully armed Brigade of 4,500 men was to enlist just 21 volunteers to his cause. Regardless, the raid would go ahead.

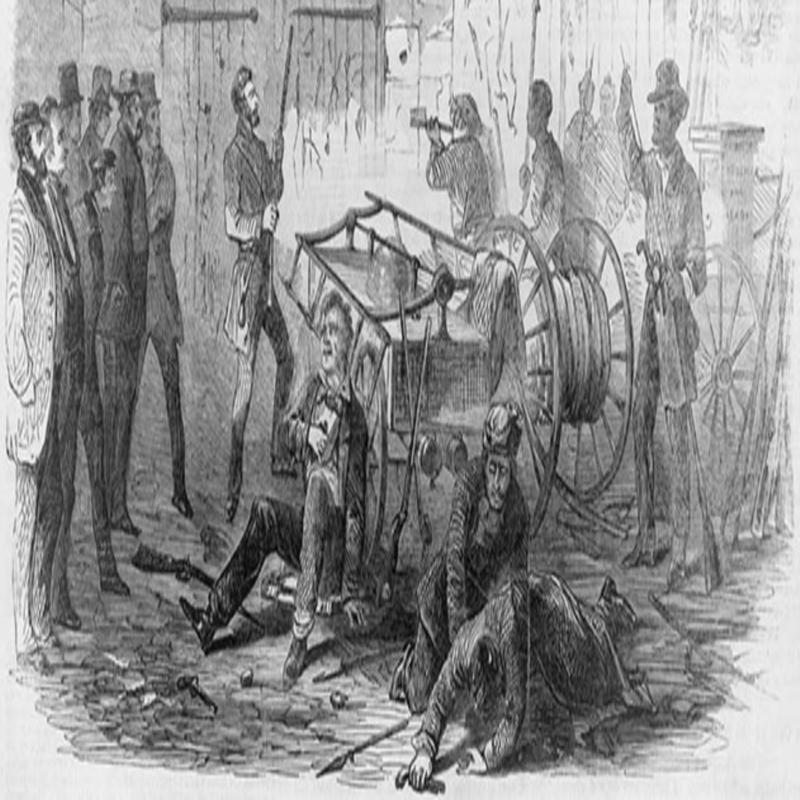

On 16 October 1859, Brown led his small force to the town of Harper's Ferry where they easily seized the Armoury. It contained the 10,000 muskets he intended to arm the slaves he felt sure would flock to his cause once the news of what had happened spread. Once all the slaves in Virginia had been freed, he would march south at the head of his new army and liberate the rest of the Slave States.

The plan soon began to unravel however and the first man to die was a free black man, Hayward Shepherd, who worked as a baggage handler on the Baltimore to Ohio train who was shot as he tried to warn the passengers of what was happening. Hearing the commotion, the local townspeople took up arms and began to surround the Armoury and it soon came under a hail of fire. Brown's son Watson was shot whilst under a flag of truce, as was another son, Oliver. As the young man lay dying his father berated him for not doing so like a man.

A black volunteer, Dangerfield Newby was then shot and killed. Someone then cut off his ears and kept them as a memento.

By the morning of 18 October and with none of the expected slaves in sight the Armoury had been surrounded by Federal troops commanded by Colonel Robert E Lee. He dispatched Captain J.E.B Stuart to demand Brown's surrender. When he refused Lee ordered his troops to open fire. In the fighting that followed ten of Brown's men were killed and five wounded. A handful managed to escape but the remainder were captured including Brown himself.

Though the attack at Harper's Ferry had taken place on Federal property the Virginia State Governor Henry A Wise was determined that Brown and his followers should be tried in the State believing that were they tried in a Federal Court abolitionist pressure would be brought to bear for an acquittal. He succeeded and the trial was to take place in Charles Town, Virginia with Brown charged with murder, treason and inciting slave insurrection.

Brown's defence was that as he had not killed anyone personally, he could not be convicted of murder, as he owed no loyalty to the State of Virginia he could not be guilty of treason, and as no slaves had risen in revolt he could hardly be accused of having incited a slave insurrection. None of these arguments made much sense of course, nor did they make any difference to a verdict that had long ago been decided.

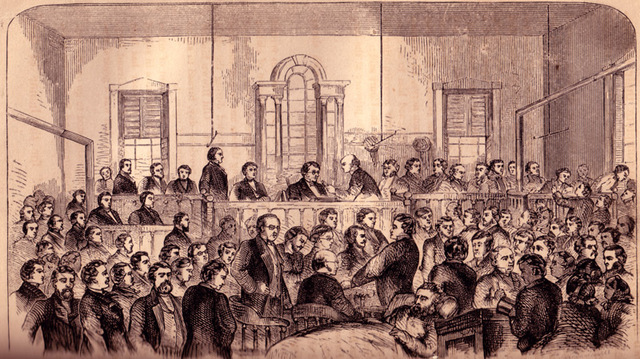

John Brown's trial began on 27 October 1859, during which he had to attend Court lying on a cot because of the injuries he had sustained in the fighting an image that was soon to appear in newspapers and magazines throughout the country eliciting sympathy in some and scorn among others. But the case against him could not be denied and it was not to be a long trial.

On 31 October, after just 45 minutes deliberation the Jury found him guilty on all charges and two days later he returned to Court to hear the sentence of death passed upon him.

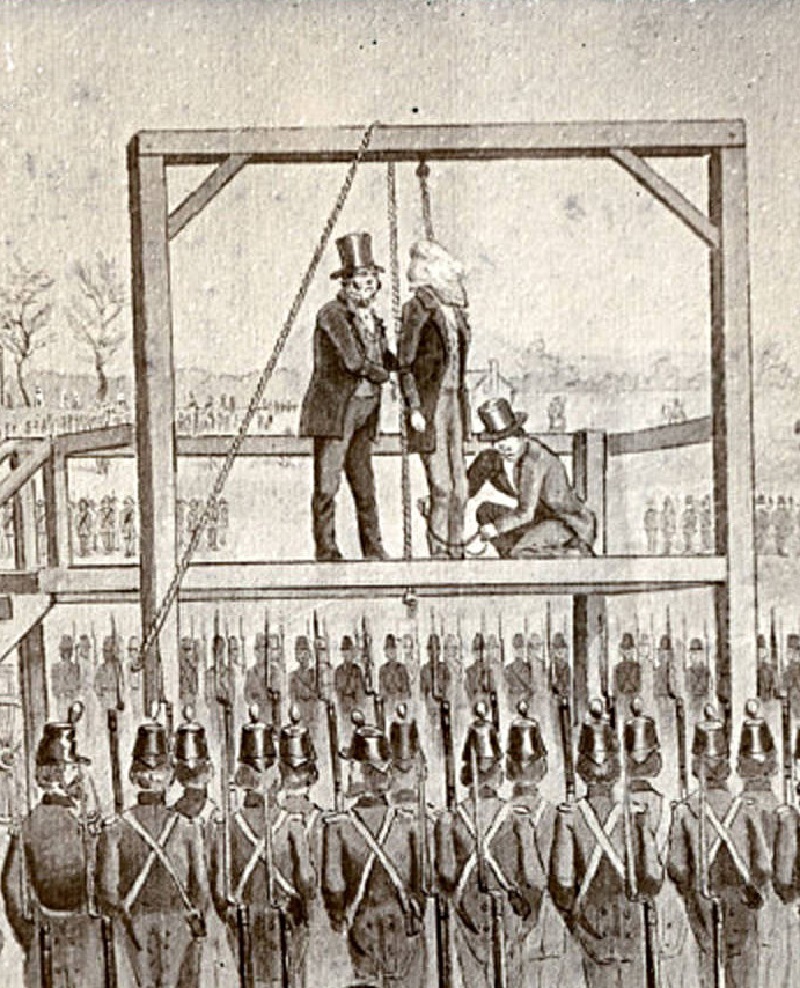

Virginia State knew that by sentencing John Brown to death they were creating an anti-slavery martyr but he had made real the South's greatest fear that there were white Northern abolitionists willing to arm the slaves to murder them in their beds and so to placate the widespread anger and calm the fears that many now had John Brown had to hang and according to the law it was the right and proper verdict and a just sentence.

But to be a martyr is more than merely dying for a cause it is to transcend the vagaries of flawed humanity to paint a glorious canvass and to create life from death thereby making the cause just.

John Brown, the Old Testament Prophet, understood this and in the month of life remaining to him he would write over a hundred letters to journalists and newspaper editors making his case. When did a higher law, the law of God, and the cause of freedom and equality outweigh those made by man he would ask? In doing so, he detailed his version of events, told his story, and created his own myth. He also wrote many times to his wife during which he made plain his intentions: "I have been whipped, as the saying goes, but am sure I can recover all the lost capital occasioned by that disaster by merely hanging for a few seconds by the neck, and I feel quite determined to make the utmost possible by my defeat. I love you dear, but I can't wait to hang".

He was to become a cause celebre on both sides of the Atlantic but a contentious, divisive and troubling one.

John Brown was hanged on 2 December 1859, and in the crowd to witness his final moments were two men who go on to make their own mark on history. The noted Shakespearean actor and future assassin of Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth who had borrowed a Virginia State Militia uniform so he could attend; and the Deputy Head of the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J "Stonewall" Jackson.

Brown made no statement from the scaffold, instead he handed a note to a female black attendant. It read: "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood".

John Brown's execution divided public opinion across America. Did his actions hasten the Southern Slave States decision to secede from the Union? Did he make war inevitable? To a great many in the South he was the demonic representation of the newly formed Republican Party, one of so many Black Republicans. Their aim to see Southern society subverted, their culture destroyed and the white man-made slave in his own home. To some he was a Godly martyr, to others a common criminal and murderer.

Frederick Douglass, who suspected of involvement in the insurrection, had fled to England via Canada following a warrant for his arrest wrote of John Brown: "His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light his was as the burning sun. I could live for the slave - John Brown could die for him".

Abraham Lincoln, who as President would less than three years later on 22 September 1862, in the midst of war issue his Emancipation Proclamation effectively ending slavery in the United States, was unequivocal in his opinion of Brown: "He was a delusional fanatic who was justly hanged".

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: