John Clare: The Peasant Poet

Posted on 4th February 2021

Unlike his contemporaries Byron and Shelley, John Clare was of no background, he had no status, and he had no money. It was not for him the gilded dreams and fantastical musings of high-minded aristocrats. He was a man who got his hands dirty - he was the peasant poet.

The early nineteenth century was a time of great change and uncertainty, science was advancing and technological innovation on the increase, industry was burgeoning, common social bonds were being broken and there was revolution in the air. For some it was a time of hope for better times ahead, for others it was a time of sadness and despair for what had been lost. It was then a time of both dreams and nightmares, and it spawned both in word and deed.

John Clare was born the son of a farm labourer on 13 July 1793, in the village of Helpstone in Northamptonshire. Regardless, that he had been working in the fields since childhood the young John was still able to attend the local Church School, which he did until the age of 12.

He did well at school being a bookish sort but then at barely five feet tall he wasn’t really cut out for games. Indeed, he was very conscious of his lack of height as he was also his stammer which he thought so severe he preferred to communicate via the written word than speech remaining silent for long periods of time.

At the age of thirteen he got a job working as a pot boy serving the customers their drinks at the Blue Bell Inn and it was here that he fell in love for the first time with a prosperous farmer’s daughter named, Mary Joyce. It appears that she was quite fond of him too but her father believing him to be of common stock and with no prospects forbade her to see him. Unable to continue in his job at the Blue Bell Inn the young John took to working the land, but he never really felt comfortable in the company of his fellow farm labourers many of whom were illiterate and did not share his passion for books and the written word. Indeed, he wrote scathingly of them: “I live here among the ignorant like a lost man, they are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.”

But then John Clare was not in love with his work rather he was in love with nature:

I fled to solitudes from passions dream

But strife pursued – I only know I am

I was being created in the race of men

Disdaining bounds of place of time

A spirit could travel o’er the space

Of earth and heaven, like a thought sublime – tracing creation

Like my Maker free – a soul unshackled – like eternity.

Despite working as a gardener for the Marquess of Exeter at Burghley House, and as a lime-burner he soon found himself doing the very thing he so despised, planting hedges and putting up fences to enclose the common land. He made little money however and in 1817 unable to feed himself he was forced to accept parish relief. He continued to write however, it was his one great solace, and by 1820 he had accumulated enough poetry and the self-confidence to travel to the nearby town of Stamford where he hawked it around the local bookshops. It impressed one local editor, Octavius Gilchrist, sufficiently enough for him to pay his fare to London to meet the publisher, John Taylor.

During his short stay in the city, he met both the essayist William Hazlitt and his fellow poet John Keats. His poetry made more of an impression upon the London literati than he did, and it was published under the title “Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery.” It was a great success selling 3,000 copies in its first year, partially as a result of a great marketing ploy - Taylor had printed on the book cover “A Northamptonshire Peasant.” This was a time when nature and rural life was the natural condition of man and it was much sought after, though as a romanticised ideal rather than as fact.

The same year that he published his first book of poetry he married Martha “Patty” Turner with whom he was to have seven children, but he was to prove to be a bad husband and an even worse father. Though he laboured hard in the fields he did not understand money and struggled to provide for his family. He was too easily distracted and was often absent from the workplace instead embarking upon long walks and breathing in the air of what he saw as freedom.

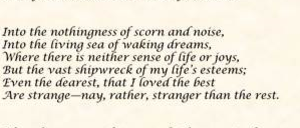

The great love he expressed in the pages of bound verse was absent in deed, and all he wanted to do was write of the beauty he saw around him and the encroaching ugliness he could not abide ugliness for everything was ugly that impinged upon the untrammelled beauty of nature, and none was more, ugly than man. It was man who drained the fens, it was man who enclosed the land and deprived the people of their right to free pasture. Never able to settle he wanted to return home, but he no longer knew where home was. He wanted to sleep beneath the stars and commune with nature, but the harsh reality was that no such paradise existed except in his own imagination:

I long for scenes where man hath never trod

A place where woman never smiled or wept

There to abide with my Creator God

And sleep as in childhood sweetly slept

Untroubled and untroubly where I lie

The grass below, above the vaulted sky

In 1821, he published his second book of verse, “The Village Minstrel and Other Poems.”

Again, it was well-received but sales were not good and it also angered him that his stock as a poet appeared to be judged upon his peasant background and not on its merits. It was as if he was a child and as the years passed his behaviour became increasingly erratic.

Always a heavy drinker he was often unwell and a difficult man to be around forever blaming his malady on someone else. Indeed, such a prickly character had he become that when a book of his poetry The Shepherd’s Calendar, failed to sell in the numbers he expected he refused to allow his publishers to retail it and hawked it around in person. It was a poor decision on his part, and it sold less than 400 copies.

Despite his poetry continuing to be much admired it made him little money and his unreliability made finding work difficult. Unable to feed and clothe his family he was only saved from financial ruin by an aristocratic admirer who in 1832 donated him a large cottage with some land of its own in the nearby village of Northborough. It was a stroke of good fortune, but he was unable to make a go of it and over the next few years his heavy drinking took its toll and he could often be found walking the countryside and the streets of nearby villages incoherently mumbling to himself.

In 1837, he was persuaded by his publisher, his family and the few friends he still had, to voluntarily commit himself to the High Beech Asylum in Essex.

Unlike most such institutions at the time it adopted a laissez-faire approach to mental illness and Clare was permitted to wander the grounds and was encouraged to continue writing. Indeed, it was whilst he was institutionalised that he wrote some of his best and most evocative poetry.

In 1841, however, he decided to remove himself from the asylum and walk home. The journey was more than a hundred miles, and it took him five days during which he slept in the ditches and ate grass which he compared to chicken. Yet, upon his arrival back in Helpstone he received no welcome, and no one was pleased to see him. In fact, he was shunned.

He told those he encountered that he was looking for Mary Joyce, the girl that he had briefly courted as a young man and had since convinced himself that he had married. When he was told that she had died in a house fire three years earlier he refused to believe it and would often be found wandering the village calling her name. He was to remain in Helpstone for five months, unwashed, unkempt, unloved and unwanted. He was later to write: “I was abroad when I was at home.”

But in truth he was becoming increasingly delusional and began telling people that he was the reincarnation of William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, and even the popular bare-knuckle boxer Jack Randall. In 1842, unable to cope with him anymore his wife Patty, had him committed to a nearby secure lunatic asylum where he was to spend the rest of his life.

In 1844 he wrote the poem An Invite to Eternity:

Wilt thou go with me, sweet maid

Say, maiden, wilt thou go with me

Through the valley depths of shade

Of night and dark obscurity

Where the path hath lost its way

Where the sun forgets the day

Where there’s nor life nor light to see

Sweet maiden, wilt thou go with me?

John Clare lived through a period of great transition. England was becoming industrialised, the countryside depopulated, and its land being turned over to commercial activity. Clare, who had so lovingly elaborated the cycle of rural life, was deeply distressed at the sight of everything he loved and lived for being destroyed. His increasingly metaphysical poetry reflected his despair and a prolonged descent into madness ensued, but it was a madness lit up at every stage by the beauty of his words and the sensitivity of his imagination.

He died on 20 May 1864, aged 71, leaving a world he thought worse than the one he had been born into but better for him having been so.

Share this post: