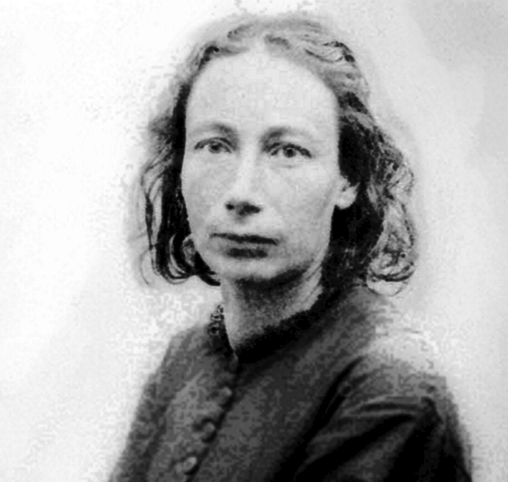

Louise Michel: Heroine of the Commune

Posted on 20th June 2021

Louise Michel who as a figure loomed large upon the barricades of Paris as the war-torn city burned around her was born on 29 May 1830, in the grim Castle of Vroncourt in the Haute-Marne region of France where her mother worked as a maidservant. She was illegitimate and never knew for certain, who her father was though it seems likely that it was either her mother’s employer Etienne-Charles Demahis or his son, Laurent.

Sent away to be raised by her grandparents she received a liberal education and permitted to roam free learned to both think and act for herself. She as a happy and carefree child and was to refer to her early years as a beautiful and idyllic time in her life.

As a young woman she returned to Castle Vroncourt to be with her mother, but Etienne Demahis’s new young wife did not take kindly to the presence of her likely step-daughter and aged 20, she was forced to leave. Still she continued to live locally whilst she trained as a teacher before moving to Paris where she hoped to open a school for the children of the poor.

In Paris she discovered the freedom of anonymity and eager to express her views and engage in political dialogue she soon became a familiar figure among the radical circles of the Left Bank. Not one to shy away from controversy her criticism of the Emperor Louis Napoleon III and her association with known Radicals such as the militant socialist Theophile Ferre with whom it is believed she shared not just violently anti-clerical views but her bed soon brought her to the attention of the police who kept her under surveillance.

When the Emperor recklessly declared war on Prussia in July 1870, Louise did not permit her radical views to impinge upon her patriotism and along with a friend Madame Leo she formed her own band of volunteers who, though mostly unarmed, rushed to the aid of the besieged city of Strasbourg. There her vehement demands that they be provided with weapons merely led to her arrest, the Authorities being more concerned about armed radicals within their midst than they were of the Prussians outside the walls.

As it turned out the French armies were so quickly crushed that there was little time to dwell upon either defence or revolution. On 27 September, Strasbourg surrendered, and Louise was released from prison immediately returning to Paris which was soon under siege itself.

In January 1871, after months of bombardment and great hardship the city fell to the Prussians and not long after the city was forced to endure the humiliation of a victory parade. As the triumphant Prussian Army with bands playing and flags fluttering marched down the Champs Elyssee, they were greeted by the stony silence of thin lines of Parisian workers who sickened by the sight of it felt they had been beaten not by the Prussians but betrayed by their own bourgeoisie who had been more interested in protecting their wealth and property than they had in defending the Honour of France. Louise shared their disgust and anger.

Following the capture and subsequent abdication of the Emperor Louis Napoleon the French were permitted to hold elections for the formation of a government to negotiate the peace settlement. A bourgeois conservative Administration was returned determined to eradicate the Radical menace they believed now dominated ‘Red Paris’. One of its first acts was to arrest known Radicals and opponents of the peace negotiations before then ordering the disarming of the National Guard.

However, when troops tried to seize the guns at Montmartre, they met fierce resistance from a people not willing to cede their only means of defence against those they considered than collaborators no better than the enemy.

Greatly outnumbered and shaken by the fury of the mob the army retreated in disorder but not before the two elderly Generals commanding the operation had been captured and summarily executed, their heads hacked off, stuck on poles, and paraded around Montmartre in an orgy of celebration.

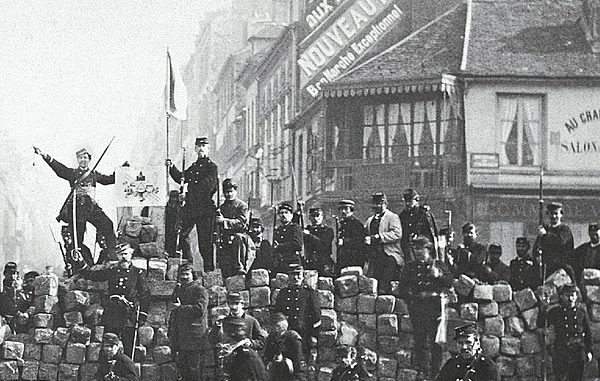

Believing the position of the Administration in Paris untenable the new Republic’s President Adolphe Thiers ordered the Government and Army to withdraw from the city and on 28 March 1871, from the balcony of the Hotel de Ville the formation of the Paris Commune was declared to wild celebrations for this was no ordinary change of Government but Revolution – the first Workers Republic had emerged from the ashes of defeat and humiliation - a new age of liberty had dawned for the common people and Louise threw herself into the cause with gusto.

But the Citizens of Paris were soon to find themselves under siege once more, not by the Prussians this time but their fellow countrymen.

Adolphe Thiers at Versailles was determined to crush the Commune with all the force at his disposal and the Prussians willingly released prisoners-of-war into his service.

The French Army surrounding Paris soon numbered 200,000 and most of these soldiers were provincials with a visceral hatred of metropolitan Paris and the ‘Red Jacobins’ who dwelt within and for many the battle to come would be vengeance for the atrocities committed during the Revolution less than a hundred years earlier.

Louise Michel was a bundle of nervous energy arranging for volunteers to provide the defenders of Paris with food and clean water and established a series of dressing stations for the wounded she knew would come once the fighting began. She also organised and armed Women’s Battalions to fight alongside the men on the barricades.

Intoxicated by events and thrilled at the prospect of the final struggle she became a familiar sight on the streets of Paris dressed in the uniform of a National Guardsman or in her signature blue dungarees with their bright red cummerbund. She was to write: “It is May 1871, and I see the red reflection of flames. It is Paris afire – that fire is dawn.”

It was said that she braved the shelling and later the bullets without flinching, that she showed courage like no other. On 21 May, Republican forces breached the city’s defences via an unguarded gate. La Semaine Saglante – the Bloody Week – had begun.

As the ferocity of the fighting increased the all-female battalions formed and led by Louise herself were drawn more and more into the conflict, and they fought well. At Belleville, a British observer witnessed their courage first hand: “They fought like devils, much better than the men, and I had the pain of seeing fifty of them being shot down after they had all but been captured and disarmed.”

But despite the often-desperate courage of its defenders the Commune was all but doomed and as the French Army closed in for the kill a last impassioned rallying cry was made by the sole remaining leader of any note, the consumptive and already dying Charles Deselescluze: “Comrades, time to man the barricades! The hour of revolutionary war has struck!”

Delescluze was killed on those very same barricades not long after as the few remaining Communards were forced into a futile and bloody last stand amid the memorial plaques and tombstones of the Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

By the end of May, Paris had fallen to the forces of reaction and more than 20,000 Communards along with some 2,000 French soldiers had been killed.

Many of the Communards had been executed after the fighting had ceased and Louise Michel now in hiding was a hunted woman. The Authorities frustrated in their efforts to discover her whereabouts arrested instead her elderly mother threatening to execute her if Michel did not give herself up. She had little choice but to do so.

Safely in their charge, Michel along with other captured Communards was made to march the 20 miles or so from Versailles to imprisonment in Satory with many beaten to death or shot along the way.

On 16 December, she was charged on seven counts of abduction, the torture of suspects, murder and treason. The charge that she had ordered the arrest, torture and execution of those suspected of being Government spies or collaborators cannot easily be dismissed given her close ties to Theophile Ferre who was to later admit such and be executed for it. The accusation tarnished her reputation at the time and has done so ever since.

She expected her trial to result in a sentence of death but rather than throw herself on the mercy of the Court she embraced the prospect of martyrdom addressing those who would pass judgement on her in defiant tones: “Since it seems that any heart that beats for freedom only has the right to a lump of lead, I too claim my share. If you let me live I will never stop crying for revenge, and I shall avenge my brothers and sisters. I have finished with you. If you are not cowards then kill me!”

But her desire to be a martyr to the cause was denied her and the blood of heroes became instead a prison ship to the colony of New Caledonia where she was sent to serve her sentence of life imprisonment. On the long sea voyage, she met another ex-Communard, Nathalie Lemel with whom she had a sexual relationship and also converted her to anarchism.

Louise suffered terribly from boredom during her incarceration but found some relief in later years when she was allowed to teach the local children to read and write. She was released and permitted to return to France in the General Amnesty of 1880 where she once again settled in Paris establishing soup kitchens for ex-Communards ostracised and unable to find work.

Re-entering the political fray, she was frequently arrested and served several further short terms of imprisonment but refused to remain silent and continued to address public meetings praising the Commune and the fight for workers freedom advocating anarchism, the dissolution of government and all the levers of authority.

At one such meeting she survived an attempt on her life when a right-wing opponent pushing himself to the front of the crowd shot her at close range the bullet lodging in her neck just missing the main artery. The would-be assassin was arrested but she refused to bring charges against him saying that he had been led astray by an evil society.

Late in life she was as famous for her defiance of convention as she was her revolutionary politics, for usurping the traditional male roles of leadership and command and for adopting male attire.

On 9 January 1905, Louise Michel died thirty-four years after the death of her beloved Commune the defining moment of her life. More than 50,000 people attended her funeral in Paris and memorial services in her honour were held the length and breadth of France. She now has a street in Paris named in her honour.

Her refusal to be intimidated and her commitment to helping the worse off in society saw her once more referred to as the ‘Good Louise’, distracting somewhat from the violence of her politics.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Women

Share this post: