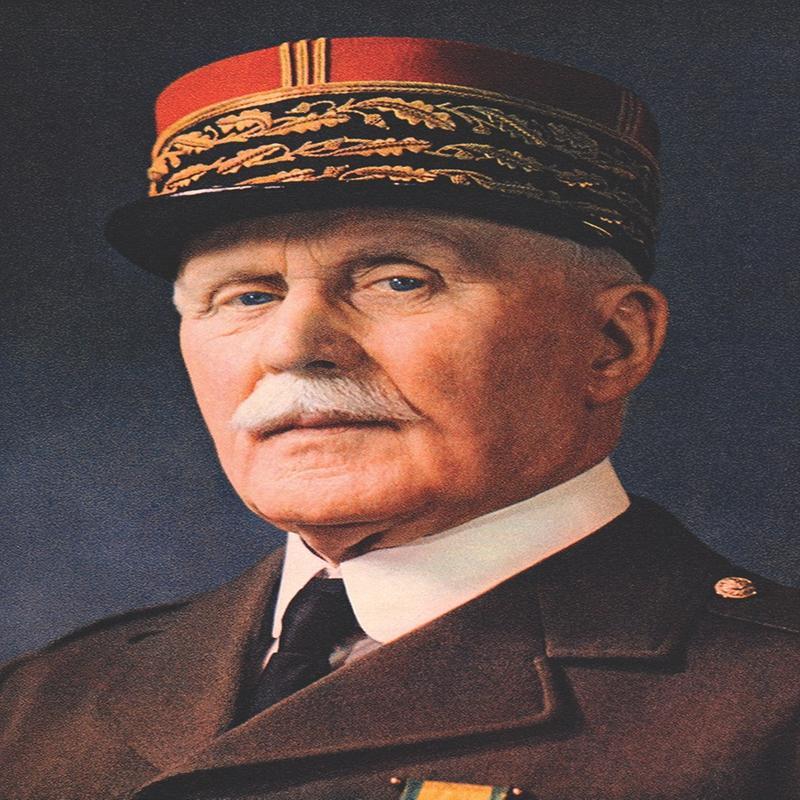

Marshal Petain

Posted on 17th September 2021

He was a recipient of the Legion d'Honneur, the heroic defender of Verdun and a Marshal of France, a man respected by his troops and admired by his countrymen. Yet in July 1945, he was sentenced to death for betraying the country he had spent his life in the service of and forever become associated with the word - collaboration.

Henri Philippe Petain was born on 24 April 1856, in Cauchy-a-la-Tour in the Pas-de-Calais region of France, the son of a farmer who inherited the traits of stubbornness, caution and stoical fatalism common to the French peasant.

He was a quiet child little given to play who grew into a reserved young man most remembered for his sustained periods of silence rather than any more obvious charms.

In 1876, he joined the French Army and attended the St Cyr Military Academy where he stubbornly refused to go along with the accepted French military philosophy of elan or the furious full-frontal assault, insisting instead that - 'firepower kills.'

His career in the army was steady rather than spectacular and his rise through its ranks painfully slow so much so that in the spring of 1914 at the age of 58 having at last made the rank of Colonel and with no further promotion possible, he bought a house and decided to retire.

The quiet life did not last long and upon the outbreak of the Great War he was recalled to the ranks where the rapid promotion he had long yearned for at last came his way and by early 1916 he was General of the Second Army stationed near the fortress town of Verdun. He proved to be a competent if unimaginative and cautious commander.

On 21 February 1916, the German Army launched a furious assault on Verdun.

The German Commander Erich von Falkenhayn had earlier targeted the town as an iconic symbol of French resistance during both the war if 1792 and against the Prussians 45 years earlier. It then played an important role in the French psyche, and he believed that they would never let it fall, and in their determination to defend it he would be able to - 'bleed the French Army white.'

Under intense bombardment the French front-line crumbled and the German’s made rapid progress, when just four days into the attack the most formidable of the outlying forts and the lynchpin of Verdun’s defence Douamont fell panic set-in.

In the early hours of 25 February, Petain who was recognised to be an expert in organised defence was dragged from the bed of his mistress in Paris and informed that he was the new Commander of the Verdun Sector.

He quickly set about reorganising the French front-line; the transport system, the so-called Sacred Road to Verdun, was secured allowing Petain to rotate troops every two weeks and maintain levels of re-supply while costly counter-attacks would cease with the emphasis instead placed on a heavy and sustained artillery bombardment of the German trenches.

Petain also made himself, known to his men and his stoicism and steely determination soon filtered through to the troops. With confidence restored the front-line stabilised the German advance was halted but it had been done so at a heavy price.

On 30 April having been promoted to command Army Group Centre Petain was replaced at Verdun by General Robert Nivelle and it was Nivelle and not a is often thought Petain who coined the phrase - they shall not pass.

The Battle of Verdun which did not effectively cease until mid-December 1916 was to cost 163,000 French and 142,000 German lives. But as bloody as it was Petain was seen as having saved the French Army from what had appeared to be an inevitable, humiliating, and morale sapping defeat and as a result he had become a national hero. Also, by refusing to sacrifice his men unnecessarily he had earned the respect of his men and the reputation of being a soldier’s soldier.

Despite his success at Verdun, he was viewed among the Allied High Command as a cautious man who had displayed an unwillingness to fight so when the Commander of the French Army General Joffre was replaced in late December 1916, Petain, despite being his most obvious successor was overlooked in favour of the more aggressive General Nivelle.

Nivelle, brash and outspoken was determined to take the fight to the enemy and he exuded confidence that his planned assault on the German held Chemin des Dames Ridge would succeed. Indeed, he was confident to the point of complacency and no effort had been made to keep the attack a secret and so when it began on 16 April 1917, the Germans were prepared and waiting.

After ten days of repeated assaults and intense fighting there were 271,000 French casualties for little if no gain. Following so soon after the trauma of Verdun the senseless slaughter of Nivelle’s offensive proved the final straw. The French soldier had simply had enough. They mutinied and refused to leave their trenches.

Officer’s orders were ignored, and some were even shot at and taken prisoner. Soldiers Committees were formed, and representatives elected from among the ranks. They would defend their trenches, they said, but there would be no further attacks. Those reserves marching towards the front-line were bleated at like sheep. The French Army appeared on the point of meltdown and action had to be taken and swiftly. General Nivelle was sacked and replaced by the only General the troops might trust - Philippe Petain.

He quickly set about trying to restore morale. He addressed the Soldiers Committees directly and told them that there would be no further meaningless waste of life. He had their trust and they believed in him. He then doubled their rations and granted extended home leave to those who had been the longest on the front-line.

Of the 629 men who were subsequently sentenced to death by Court Martial he ensured that only 20, those who had actually fired upon their Officers, were executed. That at least was the official figure. Yet again he restored the French Army's morale and ability to fight but it would be some time before they again engaged in any serious offensive.

Petain had proved himself to be an able General and one who had the trust of his men, but he remained a deeply cautious man and a pessimistic one by nature.

When in March 1918, the Germans launched Operation Michael, their big push to win the war, they adopted new tactics that included short but intensive artillery barrages, the extensive use of poison gas, and specially trained storm-troopers some armed with flamethrowers - they quickly broke through the British front-line.

The situation soon became desperate, and Field-Marshal Haig called for urgent French support but Petain refused saying that he would instead withdraw the French Army to defend Paris. But by doing so he would create a large and potentially disastrous gap in the Allied lines. Despite Haig's protestations however, Petain refused to budge.

Desperate times call for desperate measures and Haig went above Petain's head to the politicians accusing him of being a defeatist who in a panic was undermining the Allied war effort and making the prospect of a German victory more likely. He demanded he be replaced even pledging to place himself under the direct command of any replacement they chose.

It worked and the obdurate Petain, despite his popularity with the army, was forced to step down to be replaced by Ferdinand Foch who became the Commander-in-Chief of all Allied Armies on the Western Front. The German assault eventually petered out and Foch was to order a series of brilliantly executed counterattacks, in which Petain played his part, that were to lead to the general advance that would bring the war to its conclusion.

Despite his demotion Petain had had a good war, and in 1919 he received his Marshal's baton. Indeed, such was his reputation that he was persuaded, against his better judgement, to stand for the Presidency of the Third Republic, which he lost heavily.

Between the wars he was to hold several prominent posts including Inspector-General of the Army, Minister of War, and Minister of State. He was a strong proponent of the defensive Maginot Line along France's north-eastern frontier with Germany and advocated a neutral and isolationist French foreign policy.

France between the wars was hopelessly politically divided. Governments came and went with alarming alacrity, Left and Right clashed on the streets of Paris and other major cities, and there appeared to be no middle way. In such a divisive and frenzied political atmosphere, only exacerbated by the World Economic Depression and mass unemployment, it proved impossible to adopt a coherent policy for national defence and despite being personally popular Petain was acknowledged as a man of the Right, and his political superiors were often not. Anything he proposed was judged not on its merits but on his politics.

Petain, stubborn, stoical and phlegmatic was an essentially humourless reactionary set in his ways who blamed the Third Republic for the moral decay of France and feared a Communist takeover. When the General Election of 1936 returned a Left-Wing Popular Government, Petain believed it meant the death of France. The Right-Wing press agreed and began to openly declare for a dictatorship and their preferred candidate for the role was, Philippe Petain. The ageing and increasingly truculent Marshal of France appeared to agree.

He was becoming an irritant to the Government and in 1939 he was appointed Ambassador to Franco's recently established fascist regime in Spain where it was thought he would receive a more appreciative audience for his views.

By 1 September 1939, France was once again at war with Germany. The country was ill-prepared for another conflict. Years of underfunding, social division and political in-fighting had denuded the French Army of its martial spirit. There was no enthusiasm for war and the elan of previous years had gone. A defensive mentality now dominated French strategic thinking best emphasised by their misplaced confidence in the Maginot Line. They would simply remain behind their fortifications and wait for the Germans to attack them.

In the coldest winter for decades the poorly paid French soldiers froze in their trenches with nothing to do. Those soldiers returning from leave often did so drunk while many others did not return at all. The so-called Phoney War was taking its toll on French morale. In the meantime, Petain was recalled from his Ambassadorial post in Spain.

On 10 May 1940, the German Army launched its Blitzkrieg on the Low Countries. Holland and Belgium were quickly overrun and the French Commander, General Gamelin, committed the bulk of his army to France's northern frontier to meet what he believed would be the German's main thrust. But on the 12 May, German Mechanised Units struck west through the lightly defended and supposedly impassable Ardennes Forest.

By 15 May, the Germans had crossed the River Meuse and the French Army was in full retreat. France was in danger of being split in two and the armies in the north in danger of being cut-off and surrounded. Even the usually implacable French Premier Paul Reynaud felt obliged to contact his British counterpart Winston Churchill to tell him that all was lost, and France beaten. Churchill was able to stiffen his resolve, but the situation remained perilous indeed.

Despite the increasingly frantic efforts to stem the German tide by the end of May 1940, the British Expeditionary Force was being evacuated from the beaches at Dunkirk. Meanwhile, in Paris the Government was undecided what to do as preparations were made to evacuate the city. Reynaud wanted to continue the fight even if this meant abandoning France altogether and doing so from their colonies overseas. The Army High Command and Petain in particular, insisted that all was lost. Churchill declared that Petain had been a defeatist in World War One and was still one now. He offered to grant full British citizenship to all Frenchmen and absorb both countries into one if only they would continue to fight. But despite his protestations and unwavering support for Reynaud the French Prime Minister was outvoted in Cabinet and forced to resign. Petain was appointed in his place.

On 14 June, Paris was occupied. Three days later, broadcasting from Bordeaux where the French Government had been forced to flee, Petain announced to the French people that he would be seeking armistice terms. On 22 June, France surrendered.

In accordance with the Armistice terms France was divided into three zones, northern and western France including the Atlantic coast was to be occupied by the Germans whilst a small strip of land beside the Alps was allocated to the Italians to placate Mussolini. Southern France was to remain nominally independent.

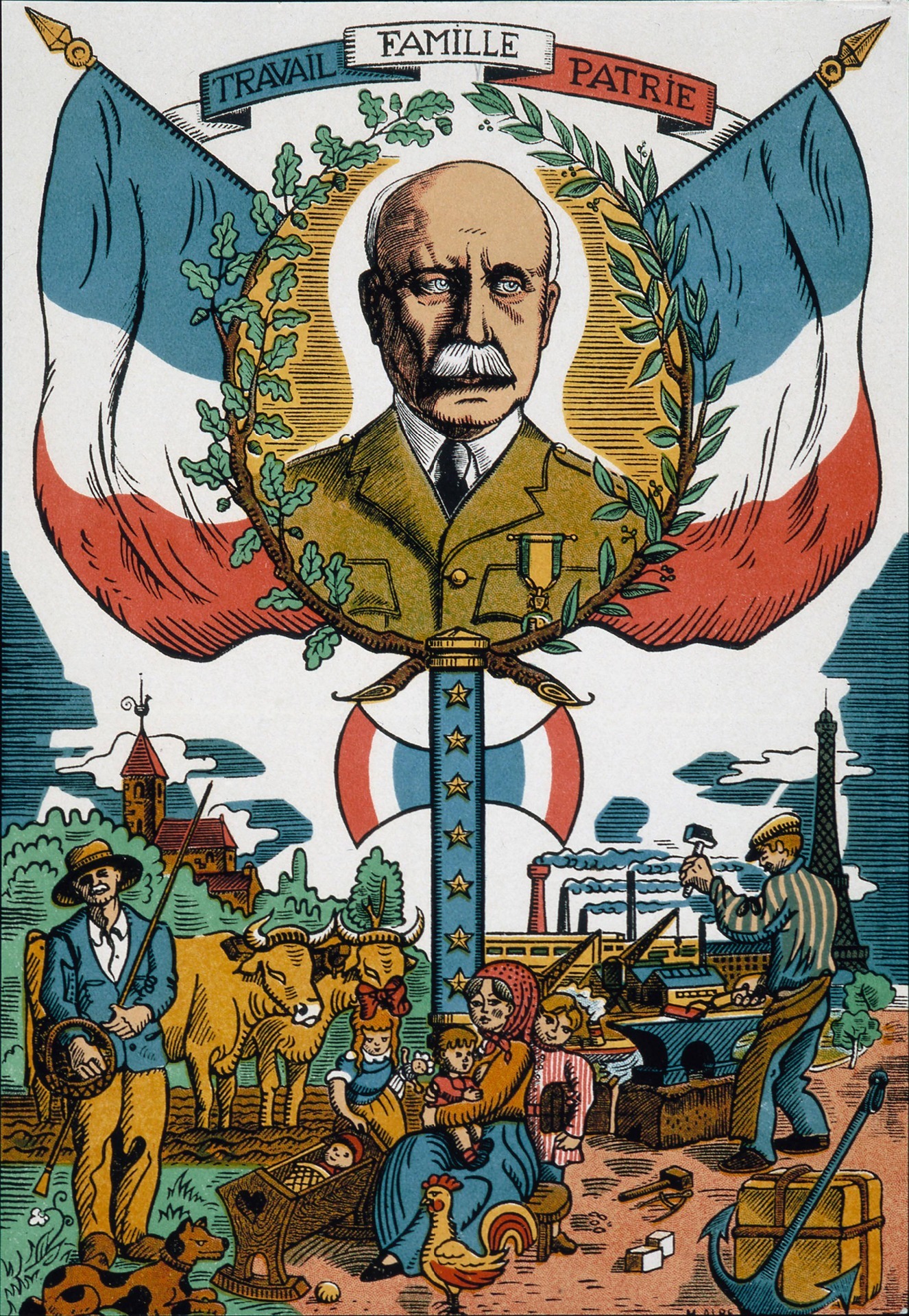

On 1 July, the French Government moved to the Spa town of Vichy and nine days later the 84-year-old Petain was appointed Head of State with full powers. He immediately set about putting France right, as he saw it.

He had long blamed the Third Republic for the corruption and moral decay that had blighted French society. The Liberal Republicanism and the socialism it spawned had been responsible for the dilution of the French fighting spirit. So France would no longer be a Republic but a State while liberal values and secularism were disavowed in favour of an authoritarian Catholic social hierarchy.

The rallying cry of the Revolution, Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite was now replaced with Travail, Famille, Patrie - Work, Family and Fatherland. The very idea of the equality of man was dismissed as an absurdity. The National Conservative Revolution was underway.

Those Civil Servants who were known to harbour Republican sympathies were dismissed from their posts and their replacements made to swear an oath of allegiance to the new regime. The Catholic Church was raised in status and expected to take a more active role in society, all criticism of Nazi Germany was forbidden, and a massive campaign of propaganda was undertaken to persuade people of the benefits of the new Old France.

On 24 October 1940, Petain had a secret meeting with Adolf Hitler at Montoire. He had been reluctant to do so but had been persuaded to attend by his Prime Minister, the egregious Pierre Laval.

Throughout their initial meeting he remained silent making Hitler believe he may actually be senile but when it came to having to discuss those matters at hand, he was to prove himself a tough and wily negotiator. Following his return, on 30 October, he broadcast to the Nation informing them of his meeting with Hitler and declaring "I enter today into the way of collaboration", words that continue to haunt France to this day.

The Vichy Regime did nothing to impede the Germans at any point. Indeed, many within the Government were eager to facilitate the Germans in any way they possibly could.

Prior to the outbreak of the war France had been a hotbed of fascist propaganda and Far-Right organisations such as Action Francaise and the Croix de Feu had been prominent, and responsible for much of the violence on the streets. Now many on the Far-Right believed they had carte-blanche to impose their wishes on the population as a whole. Petain did little to rein them in, if indeed he ever wanted to.

With little prompting from the Germans, he had already passed a series of anti-Semitic laws. So, when the Germans began rounding up French Jews for transportation to the Concentration Camps in August 1941, French Officials were enthusiastic participants. Many of these Jews were incarcerated in the most appalling conditions in the Velodrome at Drancy that was used as a transit camp. The Camp itself was administered by French Officials and guarded by French soldiers. Of the 75,000 French Jews who were transported to Auschwitz very few ever returned - Is this what Petain meant by collaboration?

On 11 November 1942, in response to the Allied invasion of North Africa the Germans occupied the whole of France. This was despite Petain ordering that French forces resist the Allies in all of France's colonial possessions. Initially they did so, but his Commander in North Africa, Admiral Darlan, who was assassinated not long after, ordered that they lay down their arms.

With the whole of France now occupied any pretence towards independence came to an end. Even so, the Vichy Government remained responsible for Civil Administration.

In January 1943, the Milice, a brutal Right-Wing Militia, was formed under the Command of the fascist Joseph Darnand, whom Petain was to appoint Secretary for the Maintenance of Public Order. They ruthlessly hunted down, tortured, and executed members of the Resistance. Petain was later to complain of their excesses, but he did nothing to curtail them. The Vichy Government also provided the Germans with a steady stream of forced labour, and as many as 50,000 Frenchmen were to join the SS. Indeed, the French SS Charlemagne Division was among the last troops defending Hitler's Bunker in Berlin in April 1945.

In September 1944, following the Allied invasion of Fortress Europe, the entire Vichy Cabinet was removed to Sigmaringen in Germany where they became a government-in-exile. Petain, by now 89 years of age, refused to co-operate any further. Instead, he insisted upon being allowed to return to France as a private citizen. He must have known that this would mean his being put on trial for his life, but he remained adamant. On the day of his 90th birthday he was driven across the border into France.

Arrested upon his return he was tried for treason on 25 July 1945.

Barring an opening statement when he questioned the validity of the Court to try him, he did nothing to defend himself and remained silent throughout the rest of the trial. On 15 August, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. Charles de Gaulle, the Head of the Provisional Government, and formally on Petain's Staff, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment on the grounds of his advanced old age and previous services to France.

Unlike so many of Hitler's other Quislings, Petain was no fascist who had a craving for power for its own sake, but he was a bigoted Right-Wing Reactionary who did a great deal of harm to his country and caused a great deal of pain to a great many people. He was misguided in believing that by collaborating with Hitler he could maintain the dignity of France.

He died in prison at IIe d'Yeu on 23 July 1951, aged 95 by which time he had been senile for a number of years.

At first the Government insisted that his tombstone should read "No Profession", but they later relented, and it was inscribed with "Marshal of France". His request that he be buried at the site of his greatest triumph Verdun, was denied, however.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: