Pals Battalions and the Thankful Village

Posted on 20th July 2021

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany embarking upon its first major conflict on the European Continent since the Battle of Waterloo almost a hundred years before but it did not in reality have an army with which to fight one.

The British Army was pitifully small compared to its great European rivals - France, Germany, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Regular Army had fewer than 300,000 men to provide for home defence and police an Empire less than a quarter the size of the professionally trained German Army. It could be reinforced of course by calling up the 300,000 veterans still on the Reserve List and the 100,000 strong part-time Territorial Army but the need for fresh recruits remained an urgent and immediate one.

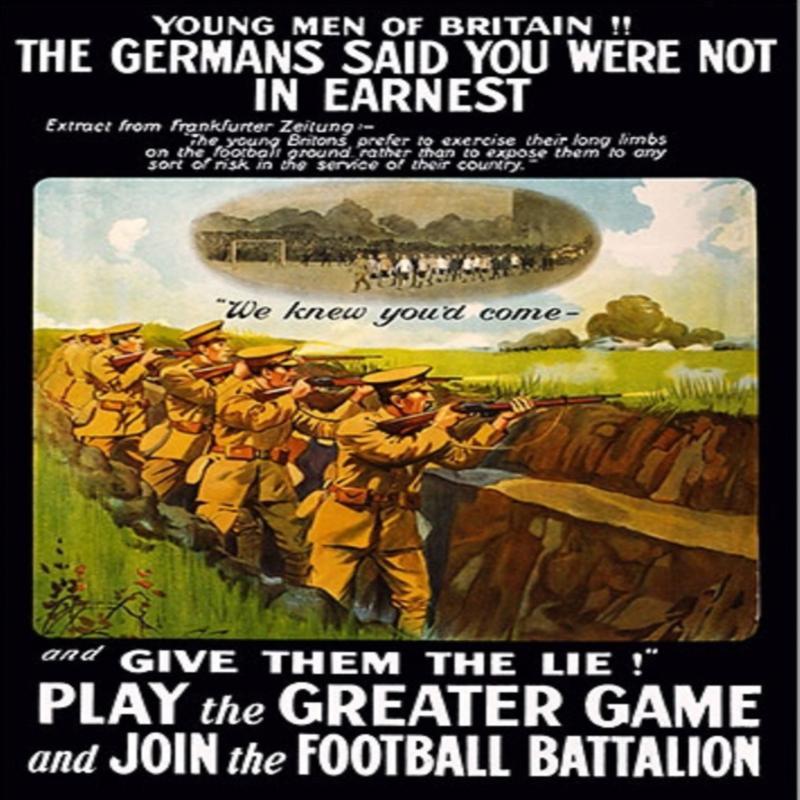

A massive recruitment drive was undertaken that saw not only the issue of the famous Kitchener Poster but the promise that those who enlisted would be able to serve alongside their friends, work colleagues or men from the same town and parish. More than Kitchener’s Poster ever did the greatest drive to recruitment was the promise of service in these soon to be known Pals Battalions.

Exploiting the enthusiasm that already existed for war the creation of Pals Battalions saw some 700,000 men volunteer for service in just two months and by the end of the year the total stood at more than a million.

Pals Battalions began to spring up all over the country; there was the Football Battalion and the Public Schools Battalion (Middlesex Regiment) the Clerk and Warehouseman’s Battalion (Manchester Regiment) the Stockbrokers Battalion (Royal Fusiliers) the Glasgow Tramways Battalion (Highland Light Infantry) and many more besides. Of the one thousand or so Battalions raised in the first two years of the conflict some 70% could be described as Pals Battalions.

As a tool for recruitment the creation of the Pals Battalions was a moment of genius, but it was to have what few at the time foresaw a devastating impact on local communities.

Few people in 1914 could have imagined the carnage of the First World War, though ironically Kitchener was one who did. He was aware that if a Pals Battalions found itself in a situation where casualties were high it would not just be the Regiment that would be decimated but the area from which the Battalion had been recruited but this was of a secondary consideration to the requirement for troops.

For the first two years of the War the brunt of the fighting was carried by the Regular Army of the British Expeditionary Force, and it wasn’t until the Battle of the Somme on 1 July, 1916, that “Kitchener’s Army” as it was known was put to the test, even though Field-Marshal Haig doubted that it was ready.

It was at the Battle of the Somme that the consequences of creating Pals Battalions first came to be bloodily exposed.

At Serre to the north of the Somme front the 700 men of the Accrington Pals lost 235 killed and 350 wounded in just twenty minutes. Such casualty figures were to be repeated elsewhere on the battlefield. The various Pals Battalions from the city of Bradford for example, were to suffer 1,700 killed and wounded in just the first hour of fighting.

For the people of these towns and the relatives of those men who were away fighting to pick up their newspaper in the morning and see page after page and name after name of young men who attended the same Church, drank in the same pub and walked the same streets who would never be returning home it was a profound shock from which it would take many decades to recover.

Such casualty figures however were to become a common feature of the war. The small village of Wadhurst with a population of just 3,200 lost 149 men killed at the Battle of Aubers. Likewise, in the small Lancashire town of Chorley 93 of the 175 men who served in the First World War never returned, and there were few parts of the British Isles that were not similarly affected.

By the end of the Great War Britain had lost close to a million men killed action but there were some places where all those who had gone to serve on the Western Front and elsewhere returned alive. Of the 16,000 parishes in England and Wales there were just 52 that lost no men killed. There were no parishes of a similar size in Scotland and Northern Ireland that were similarly unaffected.

Some of these villages had sent only one, two or three men to fight others many more and though they returned alive they were often maimed or traumatised by their experience. These villages considered themselves blessed to have all their men return but there was no war memorial by which to remember their service.

IIn 1936 the journalist Arthur Mee studying the impact of the war on local parishes referred to them as Thankful Villages and it is by this name that they have been known ever since.

Following the end of the Second World a campaign to mark the service of the men from those places where they had no war memorial saw signs posted at the entry to the village and a marker of some kind within it to indicate that they were Thankful to God for sparing them the terrible consequences of a conflict that had beset so many others.

Of the 52 villages that survived the Great War relatively unscathed 14 were to do so again in the Second World War making them Doubly Thankful Villages.

Share this post: