Queen Eleanor's Cross

Posted on 26th August 2021

Few English Kings have been more ruthless and unforgiving than Edward I, a man of steely determination and unbridled ambition, cunning, duplicitous and of whom it was said had a temper so fierce that grown men would tremble in his presence. Yet as seemingly devoid of compassion as he seemed his was not a heart made of stone and it would be broken by the death of the one person he ever truly loved, his wife - Eleanor of Castile.

Known as Longshanks for his impressive height, Edward was born on 17 June 1239 the eldest son of King Henry III whose long reign was to end in bitter dispute and war with his own Barons. Eleanor was born in Spain the daughter of King Ferdinand III of Castile and his wife Joan, Duchess of Ponthieu.

Castile was one of the most powerful Kingdoms in Europe and Henry III feared that thwarted in their attempts to expand into the Pyrenees they would turn their attentions towards his domain in Gascony, and so to secure its borders he hastily arranged for his fifteen-year-old son Edward to marry Ferdinand and Joan’s only surviving daughter the thirteen-year-old Eleanor.

It was a union that needed to serve the interests of both parties and Ferdinand believing that Gascony could serve as a bulwark against French ambitions considered it a good match, so on 1 November 1254, the young couple were married at the Monastery of Las Huelgos in Burgos.

Unlike many such arranged marriages it soon became evident that Edward and Eleanor, who were rarely seen out of each other’s company, were genuinely fond of one another and love blossomed even if the early years of their marriage were to be blighted by war.

In 1258, led by the renegade French nobleman Simon de Montford the Barons in a reassertion of Magna Carta forced the King with a furious young Edward at his side to cede power under the terms of the Provisions of Oxford to a Baronial Council and agree to the formation of a Parliament.

Six years later Henry attempted to restore his power as King by force of arms but on 14 May was defeated at the Battle of Lewes and both he and Edward were taken prisoner but following a daring horseback escape from captivity Edward was to raise an army on his father’s behalf and resume hostilities. The Second Baron’s War as it became known was concluded at the Battle of Evesham on 4 August 1265 where Simon de Montford was killed, and Henry restored to the throne unopposed.

EEdward victorious in battle was now carrying much of the burden for running the country for his aged father and at his side throughout was Eleanor who he had refused to send away during the conflict for her own safety, as was the custom.

With the country at last pacified and with his father safely restored to the throne in 1271 Edward went on Crusade and as always Eleanor accompanied him but the Ninth Crusade as it became known was not a success and Edward’s French allies after an unsuccessful campaign in North Africa quickly abandoned it.

Edward however was determined to continue to the Holy Land and arrived at the Christian capital of Acre on 7 May 1271; with only 225 knights in his retinue, it was evident that he could make little impact on a resurgent Islam but his mere presence in the Holy Land struck fear into the heart of his enemies and not long after arriving he was to be the victim of an assassination attempt.

Edward was to turn on his assailant and kill him; but during the melee, he was stabbed in the arm with the blade of a poisoned knife and it was only the swift intervention of Eleanor who knelt beside her stricken husband and sucked out the poison that probably saved him.

Despite the attempt on his life Edward was adamant that he would remain at Acre but over the next few months his condition worsened to the point where he was advised that should he stay any longer he might leave his father without an heir, and so on 24 September he made the decision to return home.

On 16 November, Edward received the news that his father had died and that he was to be King. It might never have happened had it not been for the swift reactions and timely intervention of his wife, and it was something for which he would be eternally grateful.

EEleanor of Castile was small and pretty with dark features and a pale, milky skin which Edward found particularly attractive.

With a lively personality and flirtatious in her manner the sweetness of her nature, at least in the presence of her husband, disguised a greedy eye and a steely determination. She was to prove as ruthless as the King if not in the realm of politics and war then in that of acquisition and commercial transaction. Her greed was notorious, and she was willing to both circumvent the law and issue threats to obtain what she wanted.

To deny the Queen could often result in an audience with the King, not a prospect to be taken lightly, and at a time when display was considered the true value of one’s worth it was never a good idea to flaunt your wealth in the presence of the Queen.

Edward facilitated his wife’s dabbling in the property market, her association with Jewish moneylenders, and her ruthless foreclosing on debts. He did not object to the money that found its way into the Royal Treasury and Eleanor’s willingness to undertake such work deflected the blame from Edward himself.

Eleanor was always more than the greedy harpy of reputation, she was well-read, sophisticated and her cultured ways provided a feminine silk purse to Edward’s sow’s ear of Kingship and often brutal recrimination, and she was known to temper his increasingly frequent rages and mollify his punishments.

She was also extremely pious, though never in a dour way, and established several priories but she was never charitable and refused to distribute alms to the poor at Easter as was the tradition though she was happy to let others do so on her behalf, within reason.

Edward’s Court in London apart from the occasional humorous aside by the King himself of which all present would be obliged to express their appreciation, was a place of work. In the privacy of their chambers however life between Edward and Eleanor was very different and household records show that they had a happy and playful relationship. They would tease one another with Eleanor often pretending to be angry with him and he having to pacify her anger with kisses and sweet words.

They also played games such as blind-man’s-bluff with hide-and-seek as Edward’s particular favourite. Eleanor would also often disguise herself as one of her ladies-in-waiting with Edward then having to guess which one. If he got it wrong, she would scold and mock him, much to the King’s delight.

The passionate nature of their relationship is also borne out by the twelve children she had by him, four of whom were boys, though only one, the future Edward II, lived into adulthood.

In the autumn of 1290, while Edward was deeply involved in issues regarding the succession crisis in Scotland, Eleanor came down with a fever and the procession of the Royal Court to Lincoln had to be abandoned as her condition rapidly worsened. Weak and fatigued she was forced to take to her bed, and it soon became apparent that she would not survive.

Having earlier taken confession, Eleanor died on 28 November 1290 with the distraught and tearful Edward at her bedside.

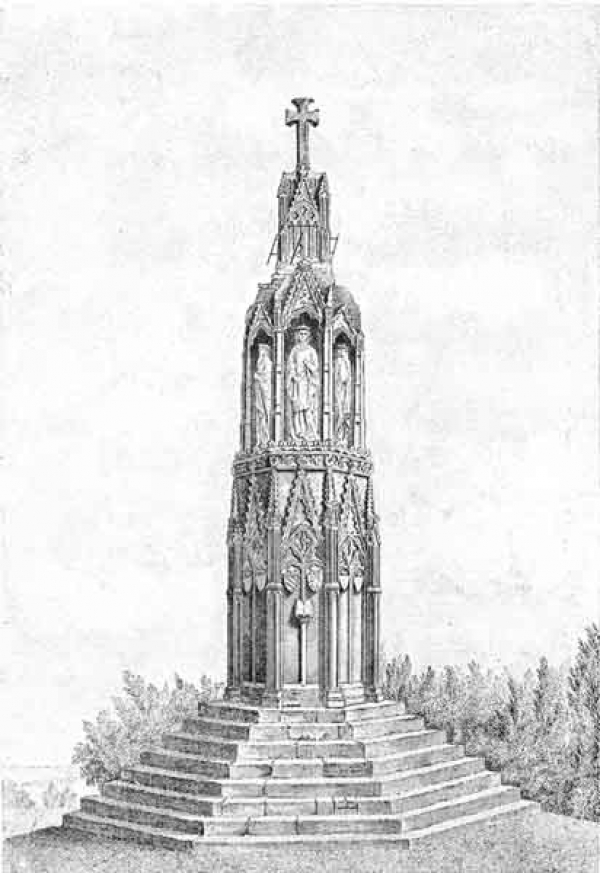

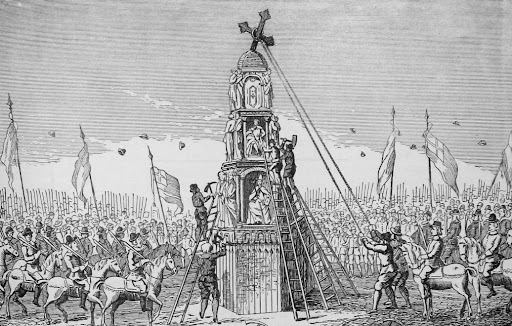

In mourning for his Queen and wife of 36 years Edward walked the return journey to London and at every stop made along the way he ordered that a statue be built to her memory and in in her honour. These statues would be surmounted with a huge cross that would serve both as a symbol of his grief and of the people’s loss. No person would be excused passing the statue without stopping to say a prayer for the repose of Queen Eleanor’s soul.

If they had not appreciated her in life, then they would be made to do so in death.

The grief stricken Edward stayed overnight at local abbeys to be closer to God at this difficult time and the monks were obliged to chant prayers throughout his tenure to ensure her swift passage through purgatory.

Meanwhile, Eleanor’s body was returned to London where on 17 December it was buried with great solemnity in Westminster Abbey.

On the anniversary of her burial Edward ordered that 49 monks each carrying a single candle, one for every years of Eleanor’s life, walk the streets of London at night to remind the people of her passing. In January 1291, Edward wrote to the Abbot of Cluny of his despair at the loss of his beloved Queen Eleanor: “Whom living we so deeply cherished, and whom dead we cannot cease to love”.

Edward did not to remarry for nine years following Eleanor’s death, an unprecedented period of time when alliances were forged through marriage and a King could never have enough sons. When his new wife, Marguerite of France, gave birth to a daughter she was named Eleanor, and not after her mother as was the custom.

Edward I, died on 7 July 1307 at Carlisle, aged 68, while on yet another campaign against the Scots. Before he died and fearing the outcome should his son ever have to face the formidable Robert the Bruce on the field of battle, he ordered that the flesh be boiled from his body so that his bones could be carried at the head of his army.

His instructions were ignored but in this final analysis he was to be proved right.

The passion of Edward’s and Eleanor’s relationship had produced not another Longshanks but a weak homosexual whose vanity, public flaunting of his sexuality and neglect of his own wife very nearly presaged the end of the Plantagenet Dynasty.

The statues that marked the stopover points of the Royal Courts funeral procession from Lincoln to London were erected in - Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, West Cheap and Charing.

As symbols of monarchy many of the statues were targeted for destruction by Roundhead forces during the Civil War and only three of them remain today and none of these are intact or have the huge crosses that once surmounted them. The best preserved is in the town of Northampton. Still, they remain potent memorials to a King’s love for his Queen.

The tombs of Eleanor of Castile and Edward I lie near one another in Westminster Abbey. On Eleanor’s tomb exquisitely carved by Thomas of Leighton Buzzard is the simple inscription: “Here lies Eleanor, sometime Queen of England, Wife of King Edward son of King Henry, and daughter of the King of Spain and Duchess of Ponthieu, on whose soul God have pity in His mercy”.

On Edward’s tomb are inscribed the words: “Edwardus Primus, Hic Est Malleus Scotorum”.

Here lies the Hammer of the Scots.

Share this post: