Queen Henrietta Maria

Posted on 9th February 2021

Charles Stuart married Princess Henrietta Maria of France by proxy on 1 May 1625, just weeks after he ascended to the throne of England. He was 25 years old, she just 15 and a Catholic.

In staunchly Protestant England this posed a problem, but it could have been worse, for she was not his first choice. He had originally intended to woo the Spanish Infanta but his somewhat ham-fisted attempts at courtship among which included dressing up in disguise, scaling walls in the dead of night, and trying to break into the Royal Apartments came to nothing when the Spanish demanded he convert to Catholicism before any betrothal could even be contemplated. This he would never do and so he would remain the frustrated bachelor for a little longer (though in hindsight it could perhaps be seen as politically wise not to have seduced a royal scion of his country’s archenemy). So, Henrietta Maria whom he had met briefly before, was very much acquired on the rebound. Even so, their union would barely be less controversial or any more popular for that.

Young though she was Henrietta Maria was no wall flower who would allow herself to be bullied or cajoled into remaining silent or concealing her true faith; rather she would flaunt it, and not long after their formal marriage ceremony in July 1626, she and her entourage very publicly visited Tyburn to pray for the souls of the many Catholic martyrs who had been executed there. She also brought with her a 40 strong retinue of priests, ladies-in-waiting and sundry court officials all of whom were French and Catholic. None of this was lost on the largely Puritan populace of London who would regularly subject her processions through the city to catcalls and jeers something she actually seemed to enjoy and would respond to accordingly. Charles was less amused, he did not like the doubt being cast upon his own faith for he was a devout Anglican, or upon his role as Head of the Church of England. He was also aware that French influence was causing resentment at Court. Finally, his patience tested beyond endurance while the Queen remained her retinue would be sent back to France but taking a firm hand with his wife did not make the newly-weds any more compatible, however. He was a reserved man, courteous and polite who kept his own council and chose his words carefully. Henrietta Maria by contrast was loud, outspoken, and flirtatious – it was not a match made in heaven.

She had after all been raised in the French Court, always less formal than it English counterpart, and a certain latitude in behaviour was often granted to those who had been exposed to it even so, the wife’s role, whether she be a Queen or not, was to be the devoted and compliant help-mate of her husband and to venture far beyond the boundaries set was unacceptable. Her domain was that of the household and the children. She was not expected to speak out of turn and certainly not on matters that did not concern her such as politics and the affairs of state. Henrietta Maria did both and often.

The young couple rowed regularly and often within the earshot of others. Indeed, for much of the time they were barely on speaking terms and Charles spent more time in the company of his father’s former lover George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham than he did his wife prompting rumours that a similar relationship had developed between them; rumours that Henrietta Maria, who loathed Buckingham, was not shy of repeating. In his turn, Charles let it be known that he could not bear to be in his wife’s presence, but all this was to change, when on 23 August, 1628, Buckingham was assassinated. He had long been a divisive figure, the cause of friction not only at the Royal Court but also between the King and his Parliament. Now without Buckingham to advise him Charles took the momentous decision to dissolve Parliament and govern without it.

As a man who demanded loyalty from his subjects Charles now found that in troubled times there were few people, he could either trust or rely upon. It resulted in a closeness developing between him and his Queen that had previously been absent - and when it came to loyalty she would not disappoint.

On 29 May 1630, she gave birth to a son and heir and their relationship began to blossom. Five further children would follow. In love with his Queen at last Charles would now seek to sell her to his people who were not.

Charles I, like his father before him was in no doubt that all earthly power emanated from a heavenly source and that he as King was the recipient of it. It was important then, that his subjects be made aware of this also and so at a time when art was propaganda, he was determined to utilise it to its full effect; but whereas in Catholic Europe art was used to empathise the Greater Glory of God in Protestant England it would raise up his Divinely Appointed Representative on Earth. It would inspire not just obedience to the Stuart Monarchy but the sense of awe in those blessed by its presence.

Like the future Queen Victoria who guided by her husband Prince Albert would use the new technology of photography to create the image of the Royal Family as respectable and bourgeois, Charles I would use art, or more specifically portraiture to enhance the power of His Majesty and to glamourise the person of his Queen.

The raw material the artist had to work with was not promising the King barely 5’4” tall was thin and drawn with a softness of skin and a delicacy of appearance that it was difficult to hide. But if Charles was no Warrior King, then his Queen was even less a Helen of Troy. Her niece Sophia of Hanover seeing her aunt for the first time described how: “the beautiful portraits of Van Dyck had given me such a fine idea of all the ladies of England I was surprised to see that the Queen, who I had seen as beautiful and lean, was a woman well past her prime. Her arms were long and thin, her shoulders uneven, and some of her teeth were coming out of her mouth like tusks. She did, however, have pretty eyes, nose, and a good complexion.”

Any such difficulties that might have presented themselves, however, would be overcome.

But not all were willing to be seduced by the Stuart re-branding and the distaste of many in England for their Catholic Queen remained. Particularly violent in their condemnation was staunchly Protestant London and none more so than the Puritan lawyer William Prynne who in late 1632 published his Histrionmatrix, a denunciation of all public entertainments but in particular the stage: “It hath evermore been the notorious badge of prostituted strumpets and the lewdest harlots, to ramble abroad to plays, to playhouses; whither no chaste or sober girls or women, but only branded whores and infamous adulteresses did usually in ancient times.”

It was a barely veiled attack upon the Queen whose love of the theatre was well known and soon after was to perform in a production of William Montagu’s The Shepherd’s Paradise. It was not the first time he had accused the Queen of being a whore and he would pay a heavy price for it. After an extended period under lock and key in the Tower of London he appeared before the Star Chamber where he was ordered to pay a £5,000 fine and sentenced to life imprisonment and to have his ears cropped and his cheeks branded with an ‘S’ for Seditious and an ‘L’ for Libeller. On the orders of Parliament, he was released from prison in 1640.

It appeared to any outside observer during the period of the King’s personal rule that all was set fair; the country was at peace, it was prosperous, and the opposition had been silenced but rarely are old disputes so easily put to bed and when the King required money, he needed Parliament to provide it and they in their turn would demand their outstanding concerns were addressed.

In the meantime, the glorification of the Stuart Dynasty continued apace but while the image of them as God’s representatives on earth so unwaveringly depicted in the work of Van Dyck, Rubens, and others may have remained untarnished the reality was very different. Charles was in a fight with his own Parliament over who governed and with the many among its ranks, who while believing he should reign demanded that he should not rule. His attempt to quash the opposition by arresting its leading members (a policy strongly advocated for by the Queen) ended in farce when they escaped the House of Commons by boat while he sat disconsolately in the Speaker’s Chair impotent and humiliated.

It had been a risky move on his part, and many believed it had been Henrietta Maria who had forced it upon him.

Her isolation from much of the Royal Court had seen her develop a close relationship with Lucy Hay, Countess of Carlisle, and that unaware of her sympathy for the Puritan cause or that she was a former lover of John Pym the primary target of the King’s arrest warrant had spoken openly of the King’s plan with her. It was she who revealed the intended assault upon Parliament to her cousin the Earl of Essex, future Commander of the Parliamentary Army. Forewarned, Pym and the others had fled by boat down the Thames.

Now with London in tumult and his authority much diminished Charles, concerned for the safety of his family, chose to abandon his capital - his absence and the power vacuum that resulted only made conflict more inevitable.

In August 1642, as the King raised his Standard in Nottingham thereby declaring war upon a Parliament, he was ill-equipped to fight Henrietta Maria was already in the Netherlands using the Crown Jewels as collateral to raise money and purchase arms. She did so to great effect but the materiel she acquired was only job half done and delivery of that materiel would be fraught with danger.

Her first attempt was abandoned when caught in a fierce storm her ship was almost shipwrecked and all aboard drowned. Undeterred she would try again this with greater success although her tiny armada was pursued all the way to the port of Bridlington by enemy warships which then proceeded to bombard the harbour while her ships were being unloaded. Indeed, so severe was the bombardment they were forced to flee to nearby woods, though she would return briefly to retrieve her pet dog which they had left behind in their haste to escape.

It was typical Henrietta Maria who always appeared to be more excited by than fearful of war, a war in which she would stand unflinchingly alongside her husband displaying the loyalty the King demanded but so often didn’t receive for it was a conflict where changing sides, often more than once, was commonplace and none more so than among the nobility.

Travelling in convoy across hostile territory the Queen safely delivered her cargo of arms, supplies, and a number of volunteer soldiers recruited in the Low Countries to the King’s capital at Oxford entering the city to much fanfare and celebratory cannon fire. Here she would remain for most of the next two years making life in the over-crowded and disease ridden city more tolerable for the King by overseeing the resumption of Court life and ensuring that the niceties of Monarchy were maintained.

By the spring of 1644 the tide of the war had turned against the Royalists, and it was decided that Henrietta Maria should leave Oxford with the younger children (the Princes would remain with the King) for her own and their safety. Charles accompanied her as far as Abingdon before a tearful farewell saw her depart under armed escort for the West Country and a ship to the Continent. It was the last time they would ever see each other.

Whether in France or the Netherlands Henrietta Maria continued to work assiduously on the King’s behalf using all her powers of persuasion, and making promises she could not hope to keep, to purchase weapons and supplies for a cause she must have known was doomed with most of the war materiel procured either captured at sea or intercepted and seized on the overland journey to Oxford. At the same time the volunteer troops promised by the many Princes and Dukes who graced her presence with fine words and brave intentions never materialised.

On 14 June 1645, the main Royalist Field Army was too all-intents-and-purposes destroyed at the Battle of Naseby and in the ensuing rout the King’s Baggage Train overrun and his court papers and private correspondence captured. While the former revealed a duplicitous nature and attempts to persuade the Irish Catholic Confederation to send troops in his support the latter, especially his reference to her as ‘Dear Heart’, expressed a slavish devotion to his Queen, both sentimental and mawkish, that only confirmed the view widely held by his enemies that she was a familiar of the devil who had cast her evil eye upon and bewitched him. The letters when published were to prove a great propaganda coup for the King’s enemies.

The Civil War was as good as lost to the King in the aftermath of Naseby, but it would take time to seal the victory, there were still pockets of resistance and stoutly defended Royalist strongholds to overcome. One of these of course was the King’s capital at Oxford which had already been under siege for some time. Charles had intended to break the siege with the help of an army recruited in Ireland but his negotiations, with the Catholic Church in particular, had broken down - it left him bereft of options.

With all hope of relief gone in the early hours of the 27 April 1646 with nothing to guide them but a solitary lantern and the campfires of the enemy King Charles I of England dressed in the clothes of a common servant and with his hair cut short, accompanied by his priest and a faithful retainer, fled the city. His hope was to find a ship that would take him to France but when this proved impossible rather than prostrate himself before his own Parliament, he surrendered to the Scottish Covenanter Army.

If Charles believed he would find solace among those from the country of his birth, he was soon disabused of it as after lengthy negotiations they handed him over to the English Parliament upon payment of £100,000 prompting the King to remark sardonically that he had been bartered rather cheaply.

Henrietta Maria did not take kindly to the endless barrage of bad news from England, she did not possess the quiet stoicism of her husband, and instead displayed an anger bordering on the hysterical denouncing all those who had ever opposed the King as traitors while being unsparing with those who put their own welfare before that of their Monarch. But as infuriated as she was, she never gave up hope.

Now a supplicant in the hands of a Parliament he had once sought to confront Charles discussed with its leading members, Oliver Cromwell prominent among them, the terms whereby he could be restored to the throne. This he did this with scant sincerity however, for he was already in secret negotiations with his former Scottish adversaries to resume the war in return for the establishment of Presbyterian Church governance the length and breadth of the British Isles. In this he was encouraged by Henrietta Maria who had by now established a Court-in-Exile just outside Paris where joined by the heir to the throne she remained a powerful figure.

With little enthusiasm for a renewal of hostilities in the country beyond the more fanatical elements any hope of success lay with the Scots Army and so when it fell to defeat at the Battle of Preston in August 1648 resistance elsewhere quickly crumbled. The King’s gamble had failed and no longer the reluctant guest of his Parliament but a prisoner of the New Model Army he was in the hands of powerful men who were quite literally willing to wield the axe if required to preserve their hard-won victory.

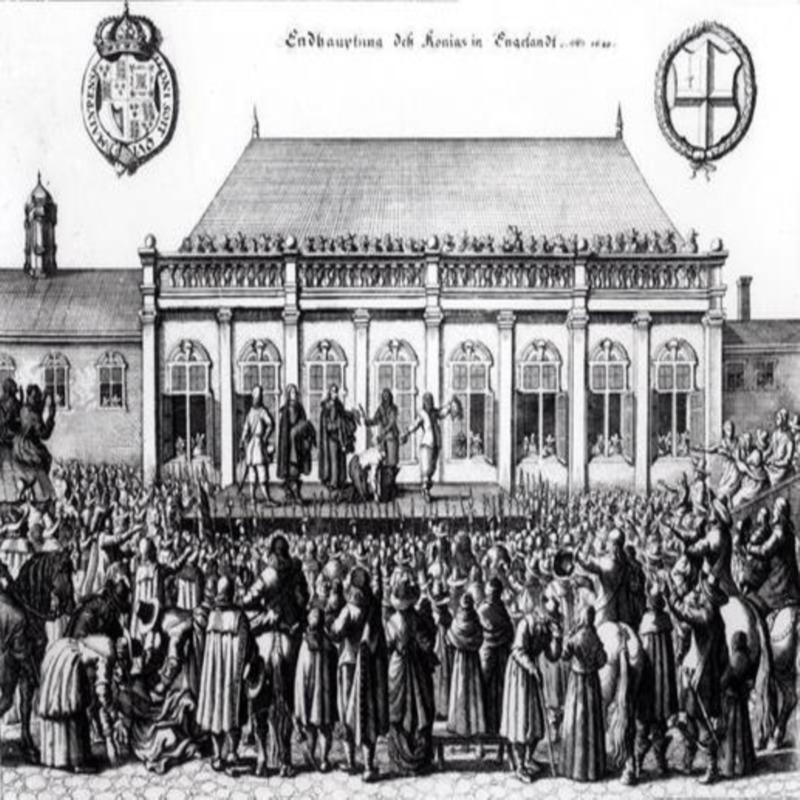

King Charles I was executed on 30 January 1649, in front of the Banqueting House in Whitehall that had earlier been decorated by the artist Rubens to the greater glory of his reign and that of the Stuart Monarchy he represented. That he died well believing to the end in the Divine Providence of his rule while bequeathing the Crown to his son did little to alleviate Henrietta Maria’s grief as she succumbed to depression and a long period of deep mourning.

With the King’s demise Henrietta Maria’s influence began to wane and she was no longer able to control a fractious Court-in- Exile whose members increasingly sought to cast blame for their predicament upon each other; that responsibility now fell to her eldest son Charles who could unite them in his desire to reverse the decision of earlier wars and reclaim the throne that vacant left England naked before God and prey to the vicissitudes of providential misfortune.

Henrietta Maria supported her son’s attempts to regain the throne while fretting continuously over his safety particularly during the disastrous campaign of 1651 that saw him put to flight and reduced to hiding in the hollowed-out trunk of the Boscobel Oak to evade capture before finding a ship that would take him to safety.

Marginalised and no longer listened to at the Court she had created Henrietta Maria turned her attention to raising her younger children paying particular attention to their religious education.

Everything changed when on 3 September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died. As Lord Protector he had been King in all but name, now with his passing England underwent a crisis of identity – did it wish to be a Republic or not?

Before his death Cromwell had nominated his son Richard to succeed him but with little support in the country ‘Tumbledown Dick’ as he was derisively known was forced to stand down after just 256 days at the helm. A power vacuum now existed at the heart of government, but it was one that General George Monck for one, was willing to fill. A former Royalist who had changed sides during the Civil War and become one of Cromwell’s most loyal supporters Monck had no desire to seize power for himself but with Parliament having proven itself unfit to rule without instruction on more than one occasion he was not willing to see it plunge the country once more into chaos and bloodshed. On behalf of Parliament, with or without their permission, his representatives opened negotiations with those of Charles II for the terms by which the Stuart’s could be restored to the throne. Concessions made by both parties saw Charles depart the Netherlands for England arriving in London on 29 May 1660, to a rapturous reception. After eleven years in exile, he had been restored to the throne that had been so brutally torn from his father’s grasp.

Henrietta Maria was delighted by the Restoration but disappointed her son had signed the Declaration of Breda that had accompanied it. He had pledged in the Declaration not to seek vengeance upon those who had deposed his father and apart from the Regicides, those who had signed the King’s Death Warrant, he would be as good as his word; but with so many of them already dead or having fled the country she saw the persecution of the remaining Regicides alone as scant justice.

She nonetheless returned to England in October 1660, to very little fanfare with far fewer following her procession through the streets of London than would once have been the case. Indeed, so dismissive was the diarist Samuel Pepys of her return he remarked upon how few bonfires had been lit in her honour and described her as: “a very plain little old woman, and nothing more in her presence or in any respect or garb than any ordinary woman.”

She had intended to remain in England in honour of her husband and to support her son, but England was a country that had brought her only pain, a cursed country that she had long ago fallen out of love with; a visceral dislike made worse when her son Henry, Duke of Gloucester died of smallpox to be followed only a few months later by her youngest daughter, Mary.

Under a cloud of melancholia brought on by the isolation of a Court she no longer recognised in 1665 Henrietta Maria returned to France where she could be comforted by the presence of friends and commit more time to her religious devotions. Her mental health improved as a result and there were fleeting glimpses of her old ebullience, but she could not deny the ravages of time and her physical condition continued to decline.

On 10 September 1669 suffering from a bronchial condition, she simply couldn’t shake off she died, aged 59.

During her years as Queen, she had never secured the affection of her people or even the respect of her peers, but she had won the love of a King, a King who she served faithfully until the end and at great personal risk to herself. It was something for which she received little credit but over time some vindication, perhaps.

Her later years were consumed by the desire to see her eldest sons convert to the Catholic faith: James did so publicly just prior to her death, Charles as King was more circumspect and only converted on his deathbed. Yet even this victory for Henrietta Maria would prove a pyrrhic one for when James succeeded his brother as King it was his Catholicism that would prove his downfall and herald the end of the Stuart Dynasty.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart, Women

Share this post: