Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima

Posted on 20th September 2021

On the morning of 19 February 1945, men of the United States Marine Corps landed on the small island of Iwo Jima, an eerie place of hard basalt and volcanic ash 750 miles south-east of mainland Japan which as part of the Home Islands defensive perimeter had become a honeycomb of tunnels, underground lairs, and deeply entrenched gun emplacements.

It was a flat and almost featureless island except for Mount Suribachi at its southern end which 528 feet at its highest elevation dominated all around it. From here the Japanese could observe everything and so it became an early target for U.S Forces.

Iwo Jima would, however, prove a tough nut to crack and the fight for its possession would become another of those bloody slogs that marked out the war in the Pacific from other campaigns. It would also provide one of the most iconic and enduring images in the history of warfare.

On 23 February, just four days into the battle a daring raid by 40 men of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment led by Lt Harold Schrier reached the summit of Mount Suribachi where at 10.20 am he along with Sergeant Oliver Hansen and Sergeant Ernest Thomas among others raised the Stars and Stripes. They did so to the cheers of those Marines already on the island and a cacophony of wailing sirens from the ships moored offshore.

But it was a symbolic not a practical triumph, a tactical rather than a strategic success for the Japanese had not yet been cleared from the slopes of Mount Suribachi and the area was far from secure.

Even so, the drama of the moment could not be denied but although there were photographers present at the flag raising, they had not captured it in quite the right way while the flag itself was also too small. It would have to done again and so it was not the men who first raised the flag on Iwo Jima who were to be lionised in the press, immortalised on the silver screen and or cast in bronze at the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery. It was not their image that would circulate around the world.

The flag used wasn’t clearly visible from every part of the island, and it was in any case rumoured that the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal witnessing events had been so fired up with patriotic zeal that he not only agreed to the flag being replaced with a larger one but wished to keep the original as a souvenir.

The Commanding Officer present Colonel Chandler Johnson ordered a more suitable flag be found and one was quickly retrieved from a destroyer moored offshore. Taken to the summit of Mount Suribachi the new flag replaced the old as the process of raising it was replayed.

It was a big deal when the Stars and Stripes had first been seen dominating the skyline of the yet to be conquered island fortress, it had been of profound significance, this was merely a cosmetic exercise, a tidying up or so it seemed; but war as brutal and savage as it is, is also accompanied by a nobility of glory that cannot be denied. In this symbolism plays a pivotal role.

As the second flag was being raised it was captured in the lens of Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal who was standing nearby. The image that emerged was so striking it has been rumoured ever since that the event was staged, something he always denied: “Out of the corner of my eye, I had seen the men start the flag up. I swung my camera around and shot the scene. That’s how the picture was taken.”

It soon became clear that Rosenthal had captured a moment that would echo down the ages for it was more, much more, than the mere depiction of weary and bedraggled troops engaged in a morale boosting exercise, the flag was a symbol of liberation planted firmly upon the soil of the oppressor, it was liberty triumphant and tyranny vanquished, it was the reason they were fighting; and as the image which appeared in the American newspapers over the next few days circulated more widely the world sat up and took notice. But while Rosenthal would be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his endeavour three of the men who had raised the flag, U.S Marines Harlan Block, Michael Strank, and Franklin Sousley would soon after be killed in action.

The surviving members of the flag raising team identified as U.S Marines Rene Gagnon, Ira Hayes, and Navy Corpsman John Bradley were ordered back to the United States where hailed as heroes and feted by the great and the good they were to help with the War Bonds Drive.

Upon their return to America, Rene Gagnon, who had been instrumental in finding a replacement flag but had arrived fairly late at its actual raising and so could not be absolutely certain who was present, misidentified one of those who appeared in the photo as Hank Hansen who had indeed helped raise the original flag, rather than Harlan Block. It was a genuine mistake but one that greatly angered Ira Hayes who disliked Gagnon and did not trust his motives. When he reported the mistake to the military authorities however, he was told to remain silent on the issue as the names had already been released to the public. When he confronted Gagnon hoping to elicit his support in correcting the error his apparent indifference only angered him further.

Differences in character alone would have perhaps been enough to engender a degree of antagonism but it may have been made worse by a broken promise from Gagnon not to reveal Hayes as one of the men who had raised the flag, though under pressure he would have had little choice but to do so. Regardless, it did little to cement a bond of trust between the two men.

No doubt Hayes was genuine in his desire that due credit be given to those who deserved it but there is little doubt that his personal animosity towards Gagnon also played a role.

But in the midst of war people care little for minutiae preferring instead the broad narrative sweep and to the American people the survivors of the flag raising on Mount Suribachi, the men in the picture, were everything their country epitomised and stood for, and they wanted to join in and celebrate their heroism.

On 20 April, to great fanfare Gagnon, Hayes and Bradley met with the recently installed President Truman at the White House before being sent on a carefully orchestrated whistle-stop tour of the country to raise morale and more importantly sell war bonds making public appearances aplenty, shaking hands, signing autographs, and giving speeches.

They even re-staged the flag-raising first for the cameras in Washington DC on 9th May and later in sold out football stadiums along with a papier-mâché mountain accompanied by dramatic music, flashing lights, and fake explosions. Doing so did not always sit easily with them but men are different, and they respond to the same things in different ways. Rene Gagnon appeared to enjoy himself while, John Bradley quietly went about his business. Ira Hayes on the other hand, found all the adulation hard to bear.

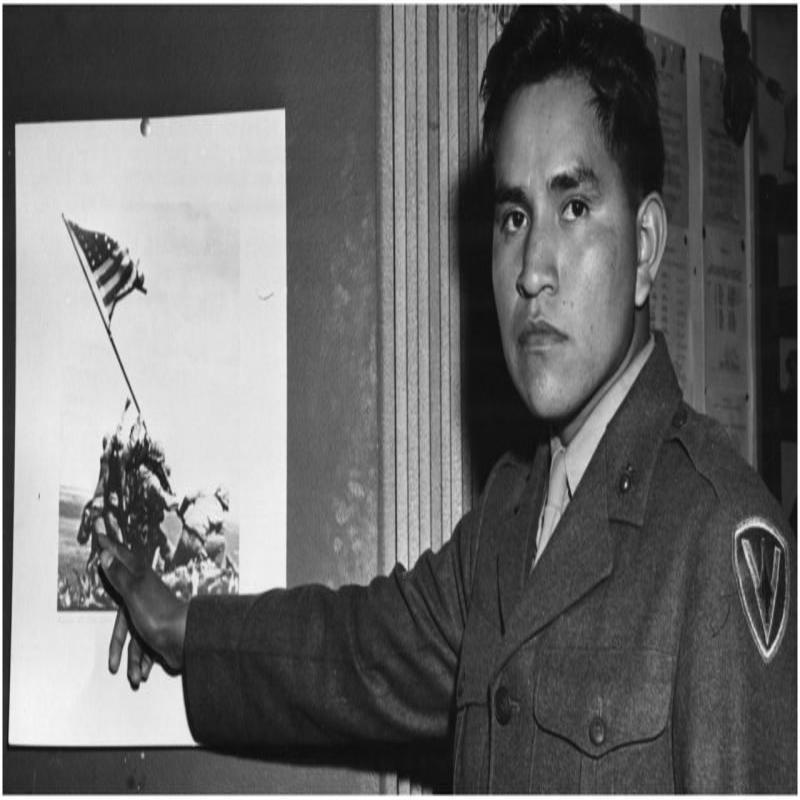

Ira Hayes was a Pima Indian raised on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona who upon volunteering to fight had been told by a Tribal Elder to be a noble warrior and he was proud of his service as a United States Marine, for him that was enough, and he struggled to understand why he should be singled out for praise having merely raised a flag where others had died. He had just been in the right place at the right time that was all. He found the attention intrusive, the praise undeserved, and the cheers rang hollow when he thought of those still fighting; “I was sick I guess. I was about to crack up thinking about all my good buddies. They were better men than me and they’re not coming back, much less going to the White House like me.”

He turned to drink to assuage his sense of guilt or at least deaden the pain, but it did neither instead becoming such a problem that in late May it saw him removed from the tour and returned to his unit.

Although he may not have considered himself a hero he could still not accept that Harlan Block had been misidentified in the photo as Hank Hansen and remained determined to rectify the matter if only for the sake of his family, and so following his discharge from the Marines in 1946 he journeyed the thousand miles or more from his Reservation to the Block parents’ home in Texas to inform them that it was indeed their son in the photo. They were able to use the information he provided to get their son’s participation recognised.

His time away from home did him good in more ways than one for as he complained: “I kept getting hundreds of letters. And people would drive through the Reservation, walk up to me and ask, are you the Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima.”

In the meantime, his addiction to alcohol worsened and it was only with great reluctance that he attended the dedication of the Iwo Jima Memorial on 10 November 1954, at which President Eisenhower and leading members of the military would be present. It was further evidence if any were needed, that the flag raising was part of his life now, that it had become folklore, and that it could only be ignored at best but never avoided.

Pictured sitting uncomfortably between Bradley and Gagnon he appeared bored by the proceedings and following a brief, somewhat faltering conversation with Vice- President Richard Nixon he declined to attend the reception held in their honour and left.

On the morning of 24 January 1955, barely two months after his last public appearance, Ira Hayes was found dead on a patch of frosted waste ground near his home. It seemed that he had collapsed and died of exposure after a night of heavy drinking. He was just 32 years of age.

Ira Hayes had never reconciled himself to his fame or indeed his good fortune. As he remarked: “How could I feel like a hero when only 5 men in my platoon of 45 survived, when only 27 men in my company of 250, managed to escape death or injury.”

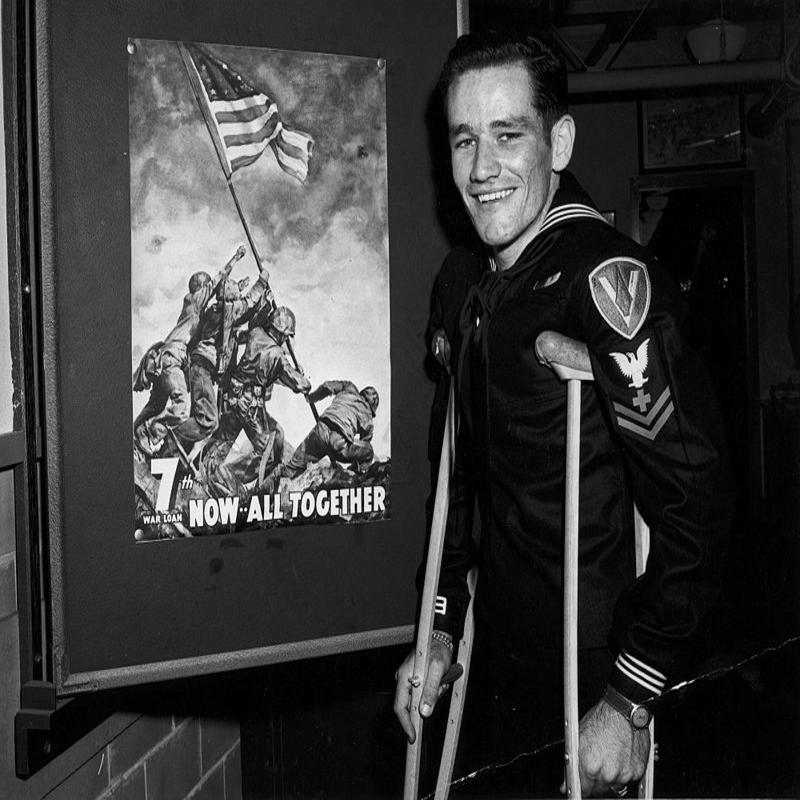

Rene Gagnon, an extrovert by nature appeared to have far less of a problem adapting to circumstances and was appreciative of the opportunity to be withdrawn from the front-line and returned home to visit the White House and be lauded and applauded wherever he went. This was no bad thing but as he was soon to discover celebrity whether borne of trivia or matters of some substance is fickle at best and often fleeting.

He had been buoyed during the War Bonds Tour by all the thanks he had received, promises of assistance should he ever require it, a level of interest from girls that he had never previously known, and the many job offers that came his way. It seemed that he would be well set once the war was over. But it is an eternal truth of conflict that upon its conclusion the first reaction is to flee from its reality and to leave its horrors behind, remembrance comes only later.

The immediate post-war years were to prove tough, the promises made to him weren’t kept, the job offers never materialised. He did in the end find work (if not of the type he had been led to expect) married and raised a family. There is some dispute as to whether he in the end became embittered about the whole affair or thought it better to let sleeping dogs lie but as the years passed, he became less inclined to talk about it. He may have done so in time, but the reminiscences of an old man were to be denied him. Rene Gagnon dropped dead of a heart attack on 12 October 1979, aged 54.

The third surviving member of the flag raising team, Navy Corpsman John Bradley, hadn’t been in the photograph at all, though this was only verified following a Marine Corps investigation in 2016. He had helped raise the original flag and was present at the raising of the second but as a spectator not a participant. The actual final member of the party misidentified as Bradley was Corporal Harold Schultz who died in 1985 long before his presence was formally acknowledged.

A quiet and reserved man Bradley had proven himself a devoted and brave sailor who had been decorated many times and now he saw it as his duty to promote the War Bonds Drive as one of the flag raisers. After all, if the War Department said he was in that photo, then he was in it even if he knew he wasn’t. But it would seem unfair to attach any blame here for none of the participants benefited much from their fleeting brush with fame.

It is likely that both John Bradley and Ira Hayes were suffering from some degree of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder which cannot be entirely ruled out for Rene Gagnon either. In the case of Bradley, he was haunted all his life by the fate of his best friend Ralph Ignatowski who had been captured by the Japanese and brutally tortured to death; the thought that had he been there for his friend it may not have happened never left him.

Having married and raised a large family he also became a successful businessman and respected member of the community in his hometown of Antigo, Wisconsin. His exploits were well known but he nonetheless declined to speak of his wartime experiences despite repeated requests to do so, which was perhaps understandable.

Navy Corpsman John Bradley died on 11th January 1990, aged 70, following a stroke.

The image of the Stars and Stripes being raised atop Mount Suribachi has a resonance that endures, perhaps it always will; but those who were its inspiration were flesh and blood infused with the spirit of humanity that for all its flaws and torments make such things possible.

Share this post: