Retreat from Kabul

Posted on 14th April 2021

The rugged and inhospitable landscape of Afghanistan served as the backdrop to the global ambitions of two great Imperial powers, Britain and Russia. For the British it was a weak point, a means by which foreign powers could gain access into an India that was fast becoming the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire. For the Russians it offered the opportunity to undermine the British and supplant them as the dominant power in the region - so they duelled with one another in what became known as the “Great Game.”

Affairs on the Indian sub-Continent were run by the East India Company as a private fiefdom on behalf of the British Government and so rapid had been their conquest of the region that they were felt by many to be militarily omnipotent, but they feared the increasing Russian influence in Afghanistan and their encroachment into India through the Khyber Pass.

In March 1839 the British Governor Lord Auckland dispatched an army to Afghanistan with the aim of achieving what we would refer to now as regime change. He was determined to replace the pro-Russian Ameer of Kabul, Dost Mohammed with the less hostile Shah Shujar.

The Afghans were a tribal people often pitted one against the other and considered little better than bandits. Few believed that they could resist the might of a disciplined British Army and as such a degree of hubris dominated the planning of the operation with little consideration given to what a military campaign to Afghanistan might entail. Consequently, the army was under strength, inadequately equipped, and poorly led.

It was also not a good time to begin the incursion with the weather still inclement and the snows not yet thawed; it was cold, debilitating and exhausting with the journey from Kandahar to Kabul particularly perilous as the column was frequently fired at from the surrounding hills by Afghan tribesmen. Upon reaching Kabul however, everything went to plan with Dost Mohammed fleeing without a fight and Shah Shujar installed as the new Ameer.

It appeared that the operation had been a complete success and the Viceroy Sir William McNaughten was privately delighted to discover that the Afghans were more than happy to be bribed into compliance with British demands. Where corruption was seen to fail the British could always use their military muscle.

For the first eighteen months everything continued according to plan but an element of complacency had set in as the British began to settle into a lifestyle that was not dissimilar to the one, they lived in India itself. The Officers invited their families to join them, a racecourse was built and Christian places of worship began to spring up around the capital. But Shah Shujar’s remit did not run much outside the confines of Kabul itself and in the countryside there was a growing resentment to the presence of the foreigner and the imposing of their ways and their religion upon them. But on the surface at least things appeared calm.

The extreme heat of the summer months and the ferocious Afghan winter ensured that the British troops remained in barracks for much of the time and as a result they appeared to have little inkling of the intensity of hatred that was developing towards them. Indeed, such was the complacency that during the summer months Sir William McNaughten and Shah Shujar departed Kabul altogether for the gentler climate of Jellalabad.

With the arrival of spring the British supply columns once again began travelling through the Khyber Pass but this time they came under repeated attack from Ghizali tribesmen and so in the summer of 1840 the decision was made to appoint Major-General William George Elphinstone as British Military Commander in Afghanistan.

General Elphinstone, who was already sixty years old, lame and in poor health had last seen combat at the Battle of Waterloo 25 years earlier; he was weak, muddled in his thinking, indecisive, and totally unfit to command an army but then no one really thought he would have much to do.

The British throughout 1840 and 1841 seemed oblivious to the trouble that was brewing and never did comprehend the deep opprobrium in which they were held. Elphinstone in particular, seemed not to have any grasp of the situation or any understanding of the kind of people he was dealing with.

He had under his command 4,500 British and 3,850 Indian troops, a force totally inadequate to the task of subduing or controlling a country the size of Afghanistan. He also had the responsibility of protecting up to 12,000 civilians – wives, mistresses, children, camp followers, and collaborators.

The British in Kabul had effectively bought the support of Afghan leaders with money and lavish gifts but now the East India Company weary of the expense ceased providing the funds required by McNaughten to continue doing so. It appeared to surprise the British that without payment the Afghans felt no obligation to remain loyal and they were shocked to find their presence unwelcome especially when abused leaving Church or physically attacked when riding out. McNaughten dismissed such incidences as rare and trivial declaring that the Afghans would always grumble a little when their palms weren’t being greased.

But tensions in Kabul reached boiling point when a mob attacked the home of the British Representative Sir Alexander Burnes murdering him and all his staff. The British were shocked at the level of violence and expected Elphinstone to respond accordingly but other than express his horror at the deed he did nothing. Later that same day Akbar Khan, the son of the deposed Dost Mohammed, sensing Elphinstone’s indecisiveness announced that he would drive the foreigner from Afghan soil. Even now, Elphinstone failed to take decisive action.

On 23 December 1841, Sir William McNaughten and several of his Afghan allies were lured to a house for a discussion with tribal elders. He had been advised not to attend as his bodyguard had failed to turn up, but he felt he had a good relationship with these people and had little to fear but upon their arrival he and the others were surrounded, dragged from their horses, and killed.

Following the attack Akbar Khan went into hiding expecting swift retaliation from the British but when none came, he ordered his men to open fire on their cantonments from the hills surrounding Kabul. Despite the rising tensions no real effort had been made to fortify the cantonments but they did offer a semblance of security, for the time being at least.

A series of half-hearted forays into the hills to disperse the rebels were easily repulsed and Elphinstone now decided that his best option was to try and negotiate his way out of an increasingly difficult situation.

He informed Akbar Khan that he would be willing to evacuate all British troops and Europeans from Kabul and withdraw to India in return for a guarantee of safe passage. Akbar Khan agreed but only if the British left their artillery behind along with several Officers to serve as hostages against their return. Elphinstone consented to these demands.

On 6 January 1842, amid a snowstorm the British Column, 16,500 strong, marched out of Kabul. Their destination was the garrison town of Jalalabad some 90 miles away.

The Column was attacked almost from the moment it left the comparative safety of the cantonments and was to advance only six miles on the first day. The Column also had no tents, and they were unable to shelter from the freezing cold and people soon began to die of hypothermia. Fearing the worst some had already taken their, own lives.

As soon as the march resumed the following morning the attacks began again. Brigadier Shelton, in command of the rearguard led a series of counterattacks in the hope of buying time for the Column but it made little difference. When the Column reached the village of Boothak, Akbar Khan agreed to meet with Elphinstone to discuss the problems it was encountering.

Akbar Khan was emollient and apologised for the attacks declaring they were the result of a few rebels who would soon be brought under control, but he also said that the anger of his people was such he needed more to placate them. He reassured the General all attacks would cease if only certain conditions were met. First he extorted a large sum of money and then insisted that the British Officers and their wives must give themselves up as hostages, and that the garrisons at Jalalabad and Kandahar must also withdraw back to India.

Elphinstone agreed to the terms set out but it was only with great difficulty that the women could be convinced to surrender themselves to Akbar Khan’s care and with good cause for although the British women were kept safe their Indian servants and the wives of Indian Subalterns he had killed.

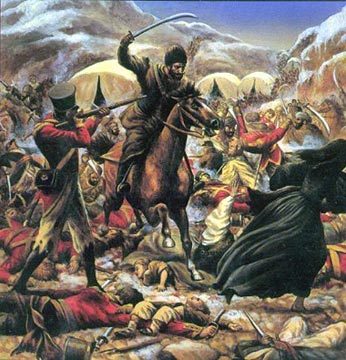

But there was to be no end to the attacks and when the Column reached a narrow gorge known as the Khoord Cabul Pass the Afghan tribesmen rained down a hail of fire from the heights that dominated it on either side. Caught in a deadly crossfire more than 3,000 were left in the gorge with those not already dead being finished off with swords and knives.

On the night of 11 January, Akbar Khan sent emissaries to persuade General Elphinstone and his Second-in-Command Brigadier Shelton to surrender themselves up as hostages. If they did so it would be the final guarantor of safe conduct. Both Elphinstone and Shelton knew by now that Akbar Khan’s word stood for nothing but by giving themselves up, they hoped to save their own skins. It was an unforgivable betrayal and the poisoned chalice of command now fell to Brigadier Thomas John Anquetil, who did his best in impossible circumstances.

Later that night the troops leading the Column found their passage blocked by a barricade of entangled thorn bushes. Surrounded by Ghizali tribesmen the British troops charged again and again to try and force a way through, but they found it an impenetrable obstruction. In desperation, Anquetil personally led an advance by British and Indian troops he hoped would lure the tribesmen away from the Column but with barely 200 exhausted and half-starved men there was little hope of success. After some initial progress the British were ambushed in the Jagdalak Pass and Anquetil was killed.

The Afghans now descended on what remained of the undefended Column and the final massacre of mostly women, children and elderly servants began.

Those troops who had survived the ambush in the Jagdalak Pass now made a last stand at Gandamark where early on the morning of 13 January in driving snow 20 Officers and 48 men of the 44th Regiment of Foot formed an impromptu square atop a small hillock. The Afghan tribesmen tried to persuade them to surrender but having learned their lesson they fought on to the end. At the last moment six mounted Officers did manage to break out but of these five were quickly cut down.

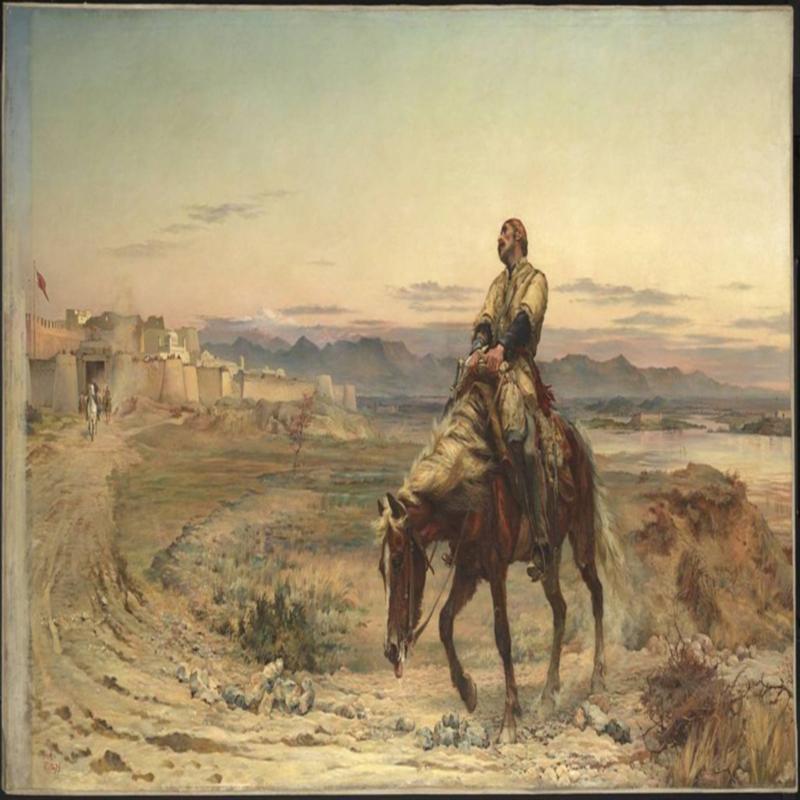

As night descended upon that grim day the garrison at Jalalabad which had been awaiting the arrival of the Column saw a lone bedraggled man on an exhausted horse. The lone rider was the Army Surgeon Dr William Brydon. When he was asked “Where is the Column?” he replied, “I am the Column.”

Dr Brydon was the sole survivor of the 16,500 men, women, and children, who had set off from Kabul just 7 days earlier. Not long after being informed of the disaster Lord Auckland had a stroke; General Elphinstone was to survive events only a few months dying in captivity of disease in April 1842, the same month that Shah Shujar was assassinated.

In the autumn of 1842, a British Army of Retribution invaded Afghanistan and upon reaching Kabul they rescued 32 Officers, 50 men, 21 children and 12 women. Those Indian troops who had survived initially were hunted down and either killed or sold into slavery.

Once the hostages had been released the British proceeded to raise Kabul to the ground, but they did not remain in Afghanistan.

Akbar Khan, the victor of the First Anglo-Afghan War died less than a year later, probably murdered by his father Dost Mohammed who with the British vanquished and his rivals all dead was restored as Ameer.

The annihilation of a British Army by Afghan tribesmen damaged their reputation for invincibility and was to have serious consequences acting as a spur to rebellion in the Indian Mutiny fifteen years later.

Share this post: