Richard II: The Boy Who Would Be King

Posted on 6th February 2021

The future King Richard II was born in Bordeaux on 6 January 1367. He was the son of the Black Prince, the heroic victor of Crecy and Poitiers, the grandson of King Edward III, and the direct descendant of the formidable Longshanks, King Edward I. Much was expected of the young Richard.

When his father, the Black Prince, died after a long illness on 8 June 1376, Richard became heir to the throne, but he was just nine years of age and the prospect of a child as King left many with feelings of unease and trepidation, that with no one able to take the helm of Monarchy dynastic squabbling and civil war would ensue.

His grandfather, the aged Edward III, had also been ill for some time and prayers were said for his survival, but they were not answered, and on 21 June 1377 he too died. There was a real fear that the young Richard’s powerful uncle John of Gaunt would now try to usurp the throne and so Richard was crowned as hastily as possible at Westminster Abbey on 16 July 1377. During the long service he fell asleep and had to be carried from the Abbey in the arms of a nobleman, as he did so the young King’s shoe fell off, for the more superstitious in attendance it was not a good omen.

Despite his Coronation for the time being at least Richard could be King in name only. The power in the land would have to lie with John of Gaunt as Regent ruling alongside the Lord Treasurer Robert Hales and the Archbishop of Canterbury Simon Sudbury.

In the decades preceding Richard’s birth England had been ravaged by the Bubonic Plague or the Black Death as it was known. This was particularly so in the years 1348 to 1350 when at least a third of the population died and the shortage of labour that resulted changed the nature of the marketplace and the conditions and wages of those workers who had been fortunate enough to survive improved significantly with many who had previously had nothing finding themselves with small fortunes to protect. Those who had previously worked as labourers in virtual servitude could now sell their labour to the highest bidder, peasants who had inherited land and small holdings from deceased relatives now began to form, a village elite.

The nobility did not take kindly to having to deal with peasants who now believed they had a stake in society and upstart labourers who demanded a fair-days pay for a fair-days work. Edward III had tried to address the issue by introducing the Statute of Labourers in 1351 that sought to peg wages to pre-plague levels but regardless of the law the labour shortage persisted, and the market dictated the terms of employment.

Fears that a child on the throne would result in political turmoil were allayed when the dynastic challenge to Richard’s reign didn’t materialise. The unpopular John of Gaunt ruled with an iron hand when he chose to do so but power for him was always a case of personal enrichment. Indeed, his love of self often allowed others on the Royal Council to exclude him from many of the important decisions. So, when resistance did come it was not to the young King’s reign but the governing class, and it emerged from an unexpected source.

In the spring of 1381, John of Gaunt introduced a new Poll Tax, a tax levied at a set rate which took no account of income. This was not the first such Poll Tax, but others had been justified on the grounds of defence of the realm and to combat the constant threat posed by the French. This Poll Tax however appeared to be nothing but straight-forward theft and those who had benefited from the Black Death were damned if they were going to have their small fortunes stolen by John of Gaunt and his cronies.

On 30 May 1381, Thomas Bampton tried to collect the Poll Tax from the people of Fobbing in Essex but led by a local man, Thomas Baker, they refused to pay, and such was the aggression displayed by the villagers towards Bampton that he was forced to flee. He later reported the incident to Robert Belknap, the Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, who decided to investigate in person.

Belknap did not travel alone but took the precaution of being accompanied by guards but upon his arrival in the area he found it in such a state of uproar that both he and his guards were taken prisoner. He was then told in no uncertain terms that not one of them would pay this iniquitous tax and was only released on condition that he vowed never to return. News of Belknap’s humiliation soon spread throughout the South-East of England and other tax resisters now emerged – the Peasants Revolt had begun.

But this was not an uprising of wild-eyed rebels but of educated men who had a plan of action and specific demands that they would take in arms to London and present to the King in person. In fact, the Peasants Revolt, as it became known, was markedly absent of peasants.

In very short order an army at least 10,000 strong had been raised and in Wat Tyler, an ex-mercenary who had recently been released from prison, they found a man to lead it. They were also encouraged by the words of the St Albans born renegade priest John Ball, who declared an end to the clergy and that no man was above any other with the exception perhaps of the King, and he asked them:

“When Adam delved and Eve span. Who was then the gentleman?”

With the promptings of the charismatic preacher to “cast off the yolk of bondage and recover your liberty” ringing in their ears they set off for London.

On their march through the countryside, they attacked the local Manor Houses that lay in their path and burned the Manorial Rolls they believed contained their tax details. They also destroyed anything they suspected might belong to John of Gaunt and hacked off the heads of anyone they thought might be informers.

The nobility was in a panic and no one knew what to do as the rebels approached London.

Sudbury, Hales, and the young King, along with his mother Joan of Kent sought sanctuary in the Tower of London while John of Gaunt fled the country altogether seeking shelter in Scotland.

The one person who remained calm throughout was Richard himself. He had agreed to meet with the rebels but for his own safety he was advised to sail down the River Thames in a barge and not travel overland. The violence of the language that was shouted at him and his entourage from the shore dissuaded him from landing and of going ahead with the meeting. Nonetheless, another meeting was set up at Mile End for a few days later.

On this second occasion he did meet with the rebels and much to their surprise consented to most of their demands, but he refused to prosecute Sudbury, Hales, and John of Gaunt. Those who were found guilty by due process of law would be punished, he said, but there would be no arbitrary arrests. Denied the vengeance they sought that night the rebels stormed London. Those soldiers who were stationed in the city terrified by the size of the rebel army opened the gates to them without a fight.

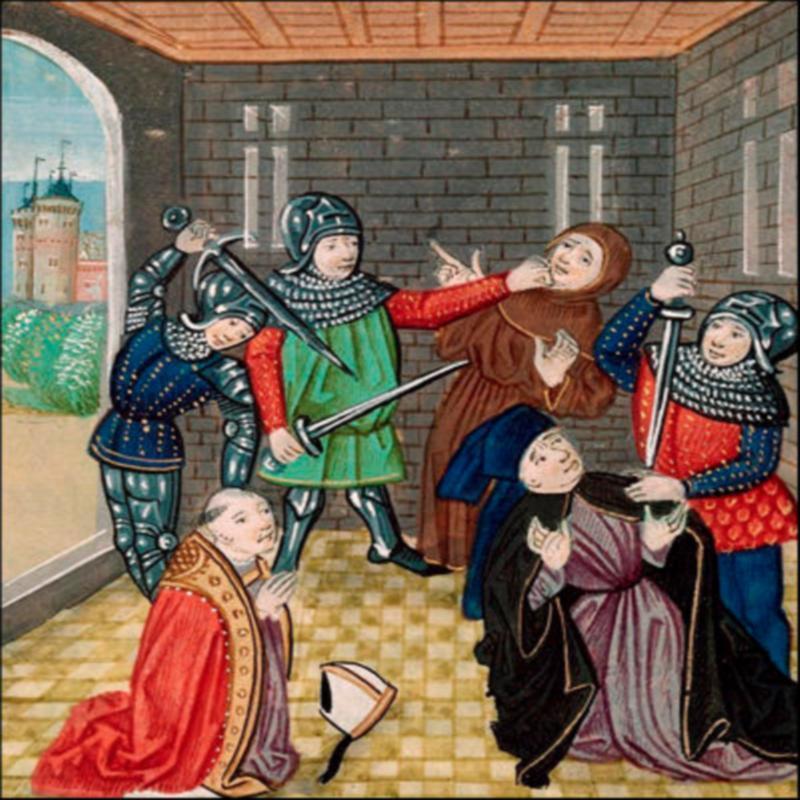

The rebels flooded in and for the first time their discipline broke down, anyone of foreign appearance was attacked and more than 150 were killed; the Savoy Palace belonging to John of Gaunt was then looted and destroyed, his wine cellar drained, and his valuable silver thrown into the River Thames while a brothel belonging to the Lord Mayor of London was burned to the ground. They then went on to capture the Tower of London where Robert Hales and Simon Sudbury were found hiding in the Chapel of St John. Despite Sudbury warning them of the interdiction of God should they be harmed they were both summarily executed with it taking seven blows to sever Sudbury’s head – the city was then set ablaze.

Richard and his mother had been ushered away to safety in the nick of time.

Despite being warned not to do so, Richard agreed to meet the rebels at Smithfield the following day.

The occasion was tense, and the massed ranks of the rebel army vastly outnumbered the small number of Knights and Attendants that the King had been able to muster. Wat Tyler confident that he had the whip-hand, and aware that Richard had already consented to their demands now approached the King and demanded confirmation of these concessions. His manner was rough and coarse, and he only reluctantly bent his knee before referring to the King as brother.

Despite Tyler’s lack of humility much to everyone’s surprise Richard once more agreed to the rebel’s demands. Tyler then dismounted from his horse and demanded a flagon of ale. Having downed the ale, he remounted and without so much as a nod of acknowledgement to the King started to ride back to his army. As he did so a young Esquire shouted that he was a thief. Tyler rounded on him aggressively but as he did so William Walworth, the Lord Mayor of London, who had taken a hard line all along, struck him in the neck with his sword. With blood gushing from his neck Tyler rode on for a while before falling to the ground. The Royal troops were upon him in an instant finishing him off.

Richard was in a precarious position, if the rebel army attacked now a massacre would ensue. A clash seemed inevitable when suddenly he rode towards the rebels shouting as he did so: “You shall have no Captain but me.”

The words had been carefully chosen to sow confusion within the rebel camp. What did they mean, was he now their leader as they had always wanted? Or was it a reassertion of Royal authority? The rebels retired, the army broke up, and they began to make their way home.

Over the next few months Richard’s many concessions were withdrawn and the rebellion crushed with its leaders rounded up and hanged.

At the age of just fourteen Richard had faced down the most serious rebellion to ever confront a reigning Monarch. Where others, including his uncle John of Gaunt had lost their nerve, he had remained strong. He had behaved like a real Plantagenet, a true heir to Longshanks. But he was still a minor and the reins of power had to be handed back.

The following year on 20 January 1382, Richard married Anne of Bohemia and though it was first and foremost a political marriage it appears that he genuinely loved his wife and was to remain faithful to her for the rest of his life. This was unusual to say the least and his not taking a mistress just fuelled the feeling that there was something not quite right about this King.

Unable to exercise power directly Richard began to gather around him a group of trusted advisers and friends who could act as a bulwark against the ambitions of John of Gaunt and others. But they had not been drawn from among the usual suspects, his Lord Chancellor Michael de la Pole was the son of a wool merchant and Simon Burley had been his tutor, whilst Robert DeVere was a childhood friend and champion of the tilts.

The nobility resented Richard’s choice of favourites, particularly as it excluded them. They were, after all, the Peers of the Realm, yet they had been removed from the King’s inner-circle.

Physically, Richard like all the Plantagenet’s cut quite a dash. He was six feet tall, with pale skin, clear blue eyes, and long blonde hair. He was certainly an intelligent man, but he could be thoughtful and thoughtless in equal measure. Sensitive to a degree his character appears to have been defined by a child-like petulance, he was prone to hysterical outbursts, and it was not unknown for him to cry, something that Plantagenet’s did not do. It was womanly behaviour and a cause for concern – some thought he lacked masculinity; others suspected him of being a homosexual.

He was also no Warrior King, rather than trawl over the plans for a new fortress he had Westminster Hall rebuilt. He was an enthusiastic patron of the arts, and the Royal Court took on a sumptuous character never before known. He had numerous paintings commissioned that depicted him in the presence of saints, those coming into his presence were expected to bow and bend their knee and he insisted for the first time that he should be addressed as Majesty. Courtiers were also expected to behave with civility even at mealtimes and were now expected to eat their food with a spoon or a fork, and he introduced the pocket handkerchief into England which soon became the must have fashion accessory.

This was not the Plantagenet way, they built fortresses and waged wars of conquest, Richard instead made peace with France. Those military campaigns he did embark upon he did so half-heartedly – where was the loot, where was the plunder. How was a Knight to get rich in Richard’s England?

In 1386, fearing that there was a plot against him John of Gaunt left England for Spain. This afforded Richard the opportunity to assert himself. It had also come at a time when the threat of a French invasion appeared imminent, and Richard demanded taxation at an unprecedented level to meet the danger. But when in October 1386, Michael de la Pole in his capacity as Lord Chancellor approached Parliament for its consent, they instead demanded his resignation. Richard was furious and said that he would not dismiss so much as a scullion from his kitchen at Parliaments request. But reminded that he was still officially a minor and was required to rule through his Council he reluctantly had to yield to their demands. But he was determined to fight back.

He set out on a tour of the Shires around London trying to drum up support for his position and secured a ruling from the Chief Justice Robert Tresilian that Parliament’s conduct had been both unlawful and treasonable. Upon his return to London however he was greeted by the Duke of Arundel, the Duke of Gloucester, and the Earl of Warwick who presented him with a writ for the arrest of De la Pole, Burley, DeVere, and Robert Tresilian on charges of ‘Abusing the King’s Youth.’

Richard raised a small army under the command of Robert DeVere in defiance of Parliament and his Council but in December 1387 it was easily defeated at the Battle of Radcot Bridge and though De la Pole and DeVere escaped in time Burley, Tresilian and others were arrested and executed.

Richard had been unable to resist the so-called ‘Merciless Parliament’ of February 1388 and from now on the country would be run by the Lords Appellant – Gloucester, Arundel, Warwick, Derby, and Nottingham. Richard responded to this by going into a long sulk refusing to attend Council meetings or to grant audiences to the Lords Appellant, instead he could often be found sitting alone in silence wearing his crown. This has led some to believe since that he may have been a manic-depressive.

On 3 May 1389, Richard at last came of age and was able to rule in his own right. John of Gaunt had also since returned from his self-imposed exile in Spain and with their differences patched up, Richard allowed himself to be guided by his uncle.

For the next eight years he ruled with moderation keeping the Lords Appellant in their positions of power and influence but unknown to them, he still harboured desires for revenge and when his beloved Queen Anne died of the plague on 7 June 1394, his one last restraining influence was removed. The only other that could have influenced events was John of Gaunt, but he was old and ailing and often forced to take to his bed.

Richard struck in July 1397, when the Lords Appellant Gloucester, Arundel, and Warwick were arrested and charged with treason.

IIn September, Arundel was put on trial for his life and took refuge in a previous pardon that had been granted by the King. Richard now revoked his pardon and in the furious row that followed Arundel spoke plainly to the King accusing him of being a breaker of oaths. It made little difference, and Arundel was executed. Richard then ordered the murder of the Duke of Gloucester who was smothered in his bed while under lock and key in Calais. The Earl of Warwick was also sentenced to death, but Richard later relented and exiled him for life instead.

He now set about persecuting those who had supported the Lords Appellant in the Shires. Officials were removed from their posts, others were imprisoned, and massive fines were levied.

Richard had little interest in recourse to the law and few formal charges were ever brought. He had ceased to be a King and had become a Tyrant and he now promoted his friends at will and surrounded himself with yes men. Only one threat now remained to his rule, the House of Lancaster in the form of John of Gaunt’s son, Henry Bolingbroke.

Richard was childless and people now looked towards Bolingbroke or the Earl of March for the succession. But the Earl of March appeared disinterested and was anyway thought to be too close to Richard.

In December 1387, Bolingbroke reported to the King that Sir Thomas Mowbray was spreading rumours that he had been close to the Lords Appellant and that to have been so treasonable and liable to Royal retribution. For a Peer of the Realm to accuse another Peer of the Realm of treason was a treasonable offence itself. Mowbray denied the claims and a fight broke out. As they were obviously so eager to come to blows, Richard ordered that they should decide the issue by combat -they would fight one another, and the victor would be vindicated in the Eyes of God.

Preparations were made for the combat and there was great excitement at Court and beyond for this fight to the death. But just as the two men were about to enter the arena Richard suddenly declared the contest void. He would decide the issue, he announced. Sir Thomas Mowbray was exiled for life and Bolingbroke for ten years.

Richard was determined that the son of his overbearing uncle would not succeed him. When John of Gaunt at last died on 3 February 1399, Richard took the opportunity to disinherit Bolingbroke, appropriate his land and estates, and change his ten-year exile to life.

Richard’s actions sent a shiver down the spine of the nobility. If he could do this to the richest and most powerful family in England, then he could do it to anyone.

Richard, confident that he had at last disposed of his enemies now chose to embark upon a military campaign in Ireland to enhance his reputation as a Warrior King; but Richard was no military commander and he had taken too few troops to obtain the objectives he had set himself, and there was little plunder to be had. All he achieved was to alienate even further the few supporters he had remaining.

At the end of June 1399, Bolingbroke, who was never going to simply accept the ruin of his family, landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire with a handful of followers. News of his arrival saw the nobility of England flock to his Standard.

Upon hearing the news Richard rushed back to England only to find that many of those Knights who had accompanied him on his campaign in Ireland now deserted to Bolingbroke, and he appeared to lose his nerve as a sense of fatalism overtook him. Instead of trying to rally support he disguised himself as a priest and with a couple of trusted retainers fled across country telling anyone who would listen to him of the traitors in their midst, and as ever blaming someone else for his troubles.

But Richard had nowhere to run to. Holed up in Flint Castle and with no one willing to come to his assistance on 19 August he surrendered himself to Bolingbroke.

What to do with the King posed a problem for Bolingbroke who did not want to be seen as having usurped the throne. So, Richard would have to be persuaded to relinquish it, and be seen to have done so. Three times he was asked to abdicate and three times he refused.

Bolingbroke was forced to enter a negotiation, laced liberally with threats, before Richard bowed to the inevitable. He agreed to abdicate the throne in favour of Bolingbroke and take the title Richard of Bordeaux, instead. Despite the agreement however, Bolingbroke knew that as long as Richard lived, he could never be secure on the throne. There were those who would never accept his right to succeed and of course the ever-capricious Richard could never entirely be trusted - as long as he lived Bolingbroke’s crown would be in peril.

Following his abdication Richard was transferred from the Tower of London to Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire where he was starved to death, a method of execution which ensured there were no marks on the body and that it could then be put on public display thereby quashing any rumours that he might still be alive and proving also that no harm had come to him during his captivity.

After all, killing a King set a dangerous precedent and when his death was announced on 14 February 1400, it was to great public mourning, much of it orchestrated by the new regime.

Despite his best efforts, Henry Bolingbroke’s reign as King Henry IV was to be blighted by rebellion and attempts at assassination. It appeared that there was no one he could truly trust and he suffered terribly from insomnia plagued as he was by bad conscience; usurping the throne and murdering his own cousin the King appointed by God never lay easily with him.

Following his death, his son Henry V had Richard’s remains disinterred and reburied at Westminster Abbey. If this was an attempt to reconcile the various wings of the Plantagenet family it failed, the divide would become a chasm and result in the thirty year dynastic struggle between the Houses of Lancaster and York we now know as The Wars of the Roses.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Monarchy

Share this post: