Richard the Lionheart

Posted on 24th February 2021

His statue stands proudly on guard outside the Houses of Parliament in Westminster as England’s Great Warrior King, yet he spoke only French, spent just six months of his reign in the country, taxed its people to perdition and complained constantly about the weather.

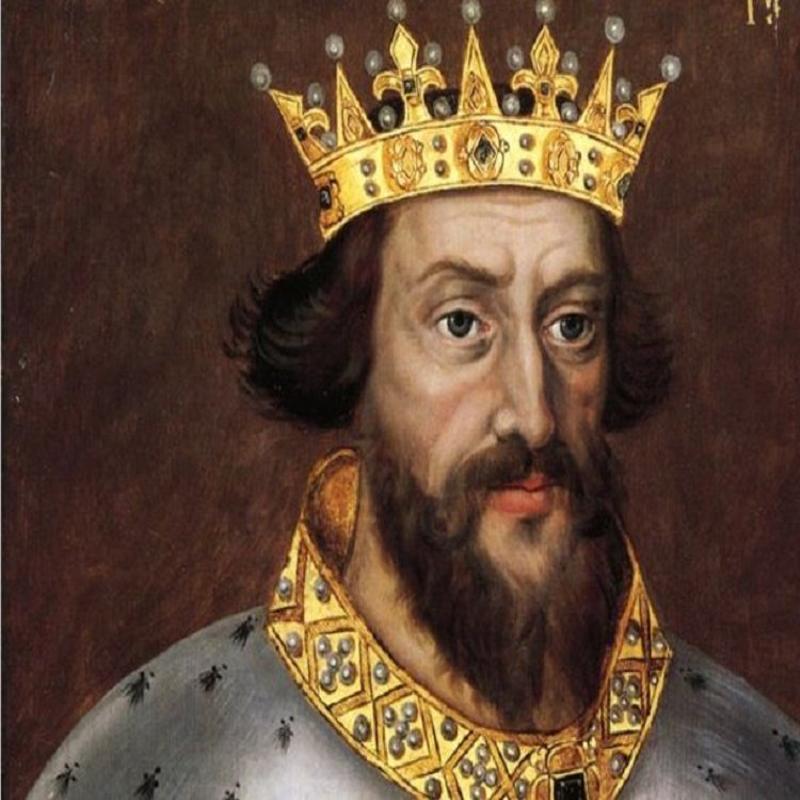

Richard Plantagenet who was born at Beaufort Palace near Oxford on 8 September 1157, was the third son of Henry II the Angevin King of England and Duke of Normandy and his formidable wife Eleanor of Aquitaine and his early life was more like the initiation into a Mafia Clan than it was a Royal Household.

Like all of Henry’s sons, Richard was raised to be not only competitive but also to have a well-refined sense of his status and nobility. He was to grow up to be the most physically impressive of the children at well over six feet tall with long golden-red hair, pale skin and piercing blue eyes. He was also the most restless, the most aggressive and the most ruthless. Indeed, he was in character the most like his father not that a shared temperament and mutual loathing would guarantee a good relationship.

In fact, Henry encouraged his children to squabble and argue among themselves and readily set one against the other in a deliberate attempt to divide and rule. In later life this was to come back to haunt him as it did little to curtail his son’s ever-increasing ambitions or increase their devotion to his person. It was also an environment in which the young Richard thrived.

Henry was always aware of the threat to his dominions posed by his neighbour the French King Louis VII with whom he had a fractious relationship readily exploited by his own family but even so, it was never as fractious as the relationship he had with his wife.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was eleven years Henry’s senior and a woman of the world who had already been divorced once, borne two children and been on a Crusade even before she ever met Henry. She was born in 1122, the daughter of William X, Duke of Aquitaine, the most powerful Duchy in France whose riches and glittering Court were the envy of Europe. On 9 April 1137, William died and his only surviving child, the already much-admired 15-year-old Eleanor, inherited the Duchy. As a consequence, she immediately became a most sought-after commodity.

As the kidnapping and rape of an heiress was known to be the easiest way for any impecunious young nobleman to acquire a Dukedom, William before his death had made provision for Eleanor to become the ward of Louis VI of France bequeathing Aquitaine to his care until she married; and the King was determined that when she did the groom would be his eldest son, also named Louis.

Eleanor was high-spirited, opinionated, and outspoken, all the things that were not expected of a woman, and it was said that she had the wit and intelligence that was the match of any man She also had a sense of adventure and was known to dress in male attire and ride the countryside unaccompanied on horseback. Indeed, her unwillingness to conform both exasperated and drove those who were her guardians to distraction.

On 25 June 1137, Eleanor married the French Dauphin Louis in Bordeaux, just fifteen days later following the death of the older Louis she was Queen of France.

The now King Louis VII quickly became besotted with the independent, free-spirited Eleanor so unlike any other woman he had ever met but the feeling wasn’t mutual. Louis was a deeply religious and pious man and whereas Eleanor was willing to commit to her religious devotions she wasn’t prepared to allow them to govern her life. Despite the distance between them Eleanor was to provide Louis with two daughters, Constance and Alix, but no son and male heir.

Taken aside by the Cistercian Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux she was told in no uncertain terms that not only was she indecorous but that she had been cursed by God for her wilful behaviour and constant meddling in matters that were not her concern. She broke down in tears and vowed to mend her ways, but they were crocodile tears for Eleanor never for a moment believed that she was to blame for the lack of male issue and she continued as before to dominate a French Court that was always more in awe of her than it ever was of its King.

In June 1147, Louis, partly in atonement for previous sins and in fulfilment of his religious duty, set off on Crusade. Eleanor insisted upon accompanying him and in her capacity as Duchess of Aquitaine leading her own troops. She even had her many ladies-in-waiting dressed as men-at-arms.

The Second Crusade wasn’t a success, however. Louis was no military commander and the Crusade was to become bogged down in a series of petty squabbles and pointless marches. Eleanor as much out of boredom as anything was to have an affair with the handsome and dashing Raymond of Antioch. It was to be a very public affair that Eleanor took little pains to hide and it was made all the more humiliating for Louis by the fact that Raymond was Eleanor’s uncle.

The Second Crusade had been a miserable failure and was ruinously expensive for the French Treasury and Eleanor was blamed by many for its lack of success. It was said that she had almost led them into a catastrophic defeat in which the King had barely escaped with his life due to her meddling in military affairs, her refusal to commit her troops to battle and her ridiculously long baggage train that she insisted on taking everywhere with her and could not be adequately protected.

In April 1149, Louis decided to return to France. By now he and Eleanor were barely on speaking terms, and they sailed for home on separate ships. By the time they arrived back in France their marriage was to all intents-and-purposes over.

Though Eleanor unquestionably enjoyed being Queen she was far from satisfied with the subordinate and compliant role that had been assigned her and was made frustrated and angry by the fact that every time she tried to assert herself it was considered an affront to her womanhood. She also found her husband physically unattractive, not that this was a requirement for a happy marriage but the rancour between the two only grew. She was tired of his puppy-eyed, child-like adoration of her and frequently chastised him for being less than a man while he bemoaned his ill-fortune in being in love with an unchaste woman. She insisted upon a divorce but Louis, despite their estrangement remained besotted with his wife and was reluctant to grant her one, his advisers less so. They wanted rid of her. As far as they were concerned, she meddled in politics, argued in public with the King and opposed many of his appointments. Louis did little to rein her in making him appear not only weak but vulnerable.

The marriage was dissolved at the Council of Beaugency in March 1152 during which Eleanor curtly informed those who were deciding upon the divorce that the lack of male issue was no fault of hers and that living with Louis was like living with a monk.

The pretext for the divorce was that as cousins they were so closely related that it constituted consanguinity and was therefore illegal. The truth was that she had failed to produce a male heir and her affair with Raymond had caused an irreconcilable rift between the couple. Louis was devastated but few in the French Court were sorry to see her go.

Single again, Eleanor once more became vulnerable to kidnap and on one occasion had to flee in the dead of night in her shift merely to avoid one particularly ambitious and amorous nobleman. The most effective remedy to this problem was marriage and Eleanor wasn’t slow in securing one. She took the initiative writing directly to the recently anointed Henry, Duke of Normandy and soon to be King Henry II of England, offering her hand. Despite her reputation as a scarlet woman, she had a significant supporter in Henry’s mother, the equally formidable Matilda. She knew that her young son would need support and impressed on him the need for a strong Queen. Henry, who had briefly met Eleanor on a previous occasion and had been struck by her beauty agreed and so on 18 May 1152, just four weeks after her marriage to Louis had been formally dissolved, they married. She had done so with what appeared unseemly haste and without consulting or seeking the blessing of Louis which went against the protocol of the day. Henry, on his part had ignored the advice of his father, an ex-lover of Eleanor’s, given many years before that he should never have anything to do with that woman.

Contrary to most people’s expectations the union between the worldly 30-year-old Eleanor and the inexperienced and naive 19 year old Henry was to be a love match. He was a tour de force, always on the move hunting, hawking, and whoring; a powerfully built bundle of energy with cropped red hair, ruddy complexion and eyes that glowered when angry. It was said that he had an agility of limb that was second to none. After years spent in the company of the pious and guilt-obsessed Louis it was difficult for Eleanor not to be drawn to Henry. Likewise, Henry quickly became enamoured with his beautiful and all-knowing wife.

She was taller than her husband, graceful and elegant and always expensively clothed and heavily bejewelled. It was said she used makeup to enhance her beauty and perfumes to seduce her admirers. Offspring it seemed was inevitable once “he had set his lustful eyes on her and she her unchaste ones on him.” Eleanor was to provide Henry with eight children proving that her fecundity and her relationship with God had never been an issue.

Their mutual adoration for one another was not to last and over the next decade their relationship began to sour as Henry a notorious philanderer began to look for his sexual gratification elsewhere. Also, and unlike Louis, he was not willing to tolerate Eleanor’s meddling in Affairs of State. Constantly harangued and brought to book by the two powerful and assertive women in his life Henry spent less and less time at the Royal Court.

Eleanor out of a sense of jealousy, revenge, and unfulfilled ambition used his frequent absences to turn their children against him. Her favoured weapon was the handsome, intelligent, physically imposing and extremely ambitious Richard. He had inherited his father’s boundless energy and military prowess, but he was very much his mother’s son.

In 1170, Henry fell seriously ill, but he had already made plans to divide his domains between his three eldest sons. Fearing that his death was imminent he now implemented them. His eldest son, also named Henry, he had crowned King of England; his second son Geoffrey received Brittany, while the thirteen-year-old Richard became Duke of Aquitaine. The King however would retain overall control and he both demanded and expected his son’s obedience.

Henry had ceded his son’s land and titles but no real power and by doing so had left them frustrated and resentful. In March 1173, angered that his father had granted his younger brother John three powerful castles in England without consulting him (he was after all King of England) and encouraged by his mother the younger Henry rebelled against his father.

Eleanor, by now living apart from Henry in Poitiers likewise encouraged her other son’s Geoffrey and Richard to join the rebellion.

Henry was now at war with his children and moreover they had allied themselves with his old enemy Louis VII. It was a serious threat to his reign, and it took all of Henry’s experience and military prowess to crush it.

He was to admonish his children for their treachery and for allying themselves with his enemy Louis VII but only verbally. In truth, he yielded to many of their demands and sought reconciliation with them not wanting to endanger the dynasty and the future of the Angevin Empire. His attitude and behaviour towards his wife Eleanor were very different, however. He was fully aware of her part in the revolt and on 7 July 1174 he sailed with her to England where upon their arrival he had her imprisoned in Winchester Castle where she was to remain for the next sixteen years. Though she would be released from her incarceration to spend Christmas with her family and sometimes on other festive occasions she now rarely saw her children, but she corresponded with them regularly constantly chiding them to oppose their father. Those rare moments she had with her children she spent mostly with Richard where she encouraged him to seek his inheritance, militarily if necessary.

For the past ten years Henry’s favourite mistress had been Rosamunde Clifford, a woman renowned for her beauty who was by all accounts the opposite in personality to Eleanor being sweet natured, compliant in all things and undemanding. Henry appreciated her simplicity and she had replaced Eleanor in his affections and was to bear him several illegitimate children.

Eleanor’s attitude towards Rosamunde is not known but it can be imagined, particularly as Henry flaunted his affair in the hope of goading Eleanor into asking for a divorce but she would not rise to the bait. When Rosamunde died suddenly and mysteriously in 1176, Eleanor was suspected of having been involved in administering the poison that likely killed her.

Henry was devastated by Rosamunde Clifford’s death but if Eleanor thought that her rival’s demise would serve to bring them closer together then she was mistaken. He merely sought solace in the arms of another lover.

In 1182, Henry’s children began squabbling among themselves once more over who should have what and the younger Henry frustrated by any lack of real power despite being titular King of England was jealous of Richard as were the other brothers who now conspired against him.

By 1183, the dispute had turned into outright war when Geoffrey and John combined with the young Henry to attack Richard’s dominions in Aquitaine. For a time an exasperated Henry stood aside from the conflict but when they also allied with the new French King Philippe Augustus, fearing that he might lose the most cherished of his Kingdoms he fought alongside Richard to put an end to it; but bringing the war to a conclusion was easier said than done but on 11 June 1183, it was brought to an abrupt halt by the death of the younger Henry of dysentery and the need to secure the future of the Angevin Empire.

In an angry and disputatious meeting with his sons, Henry declared that Richard would have to cede Aquitaine to John and take instead the Throne of England. This Richard was reluctant to do. He knew full well how little power the younger Henry really had in England which in any case was a God-forsaken and miserable place. He had always felt that he held his beloved Aquitaine in the name of his mother not his father and he wasn’t about to give it up to his idiot brother John. In the end it was only Henry’s threat to disinherit him and Eleanor’s personal intervention that persuaded him to do so.

Henry was well-aware that Richard was his mother’s favourite and that she was his confidante and as such he could not be trusted. Yet of all his sons Richard was the most like his father, he was energetic, brave, skilled in war and politically astute. Henry knew full well that the future of the dynasty and his Empire lay with Richard but could not bring himself, to accept the fact and so what affection he had he heaped on John, the most deceitful, duplicitous, and incompetent of all his sons but the only one that Henry believed he had kept from his mother’s invidious grasp and influence.

Henry and Richard were to remain constantly at loggerheads but when Geoffrey despite being warned not to participate in such frivolous and dangerous activities by his father was trampled to death by his horse at a joust, Richard became heir to the Angevin Empire, though Henry refused to formally acknowledge him as such. Instead, he appeared to favour the twenty-three-year-old John giving him ever greater responsibility and promoting him outrageously beyond his abilities.

Eleanor had been telling Richard for some time that his father might overlook him for the succession in favour of his younger brother, John. Richard, who had little but contempt for John, found this difficult to believe but such was the degree of enmity between him and his father that anything seemed possible. As a result, Richard became ever closer to Henry’s rival Philippe Augustus of France. So close in fact they were to become lovers.

By early 1188 news of the fall of Jerusalem to the Saracens had reached Europe. Fired up with religious zeal Richard and Philippe Augustus responded to the call by Pope Celestine III to recapture Jerusalem for Christ by declaring that they would go on Crusade. Henry, not one to be outdone by his son, declared that he too would go on Crusade. It was nothing but bluster, he was old and sick and had no real intention of going anywhere but he knew by his declaration he could deny Richard the funds he required to do so. Once again Henry and Richard were in conflict and by late 1188 their squabble had become war.

This time Richard in alliance with Philippe Augustus was triumphant and Henry was forced to formally pronounce Richard his heir though he privately told him that he would have vengeance - but it wasn’t to be. On 6 July 1189, Henry fell seriously ill and as he lay dying, he asked to be told the names of those who had betrayed him. When he was informed that one of the conspirators had been John it was said that it broke his heart.

The only one of his children who attended his deathbed was his illegitimate son Geoffrey by Rosamunde Clifford, whom he had made Archbishop of York. With his dying breath he told him: “My legitimate sons, they are the real bastards.”

Richard spent little time mourning the death of his father.

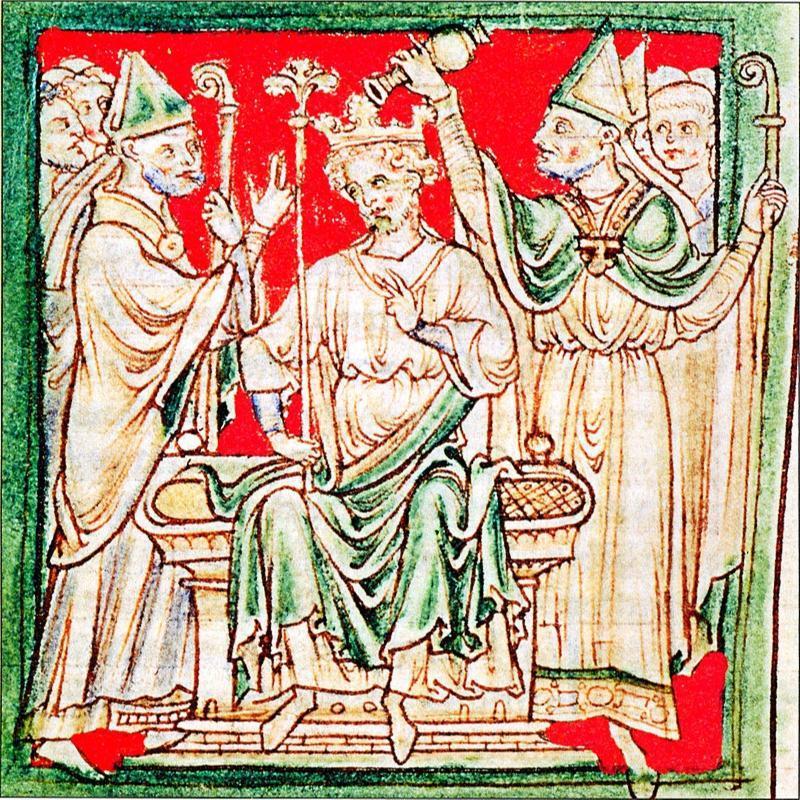

On 20 July he inherited the Dukedoms of Aquitaine and Normandy and on 3 September 1189 he was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey. One of the first things he did was to order the release of his mother from her confinement.

Rumours had spread prior to Richard’s Coronation that he was an aggressively anti-Jewish. It wasn’t in fact true, but some took the opportunity to attack Jews, beating, robbing, and in some cases killing them. The violence soon spread to attacks upon the Jewish community itself. Richard ordered the attacks to cease and executed those responsible for the more egregious violence. He also issued an edict forbidding any further attacks, but it was little enforced, and the attacks continued. It was an unfortunate and ill-omened start to his reign but in truth he was little interested in England, “a miserable country, cold and wet,” as he regularly referred to it. But it had its uses as he was to discover.

Now in control of his Kingdom, Richard was eager to embark upon the Crusade he had vowed to undertake to re-capture Jerusalem for Christ. Though he and Philippe Augustus had been lovers for some time it did not mean they trusted one another and both feared that the other would seek to usurp their Kingdom in their absence and this was in part the reason why they decided to both take the Cross and travel to the Holy Land together.

Equipping and transporting a Crusader Army was an expensive business and taxes had to be raised to pay for it which was never a popular move for a newly crowned Monarch and so the burden fell upon England always the least loved of Richards’s dominions. Indeed, he more than once expressed the view that he would sell London if he could only find a buyer.

In the end Richard was only able to raise an army of some 8,000 men and a fleet of 100 or so ships. It was hardly a force that was likely to provide the mighty Saladin with too many sleepless nights.

Despite the meagreness of the force assembled by Richard and indeed Philip Augustus, the Third Crusade was in fact a massive undertaking with the bulk of the Crusader Army provided by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, a fearsome warrior and the most powerful Monarch in Europe who had raised 20,000 knights and as many as 70,000 infantry.

Barbarossa had made good time on his march towards the Holy Land and had already defeated a Muslim Turkish Army at the Battle of Iconium in Anatolia when on 10 June he reached the Saleph River. He had previously been delayed and had fallen behind the advance guard of his army. Always insistent upon being at the head of his troops he was impatient to catch up. Seeing that the only bridge was log-jammed with soldiers and baggage he plunged his horse into the fast-flowing river determined to make his own way across, but the flow was too strong, swiftly carried him off and the 68 year old Emperor weighed down by his armour drowned.

The death of Frederick Barbarossa left his army dismayed and it quickly broke up with most returning home and only some 5,000 continuing their journey to the Holy Land. They determined to take the emperor with them however, preserving the body in vinegar before later boiling the flesh from his bones.

Richard sailed from England in July 1190, to link up with the forces of Philip Augustus but before making for the Holy Land he had a number of outstanding issues to settle. In September he arrived in Sicily.

The King of Sicily was Tancred of Lecce who had seized the throne following the death of William II. Soon after he arrested and imprisoned William’s, widow Joan who was Richard’s sister. This was an insult and Richard demanded her release and that her substantial inheritance be returned to her. If Tancred refused, he would facilitate both by force.

He did indeed refuse and in retaliation Richard captured and looted the town of Messina. Tancred continued to resist for a time but only to save face. He released Joan in March 1191, and came to an agreement whereby he delivered 20,000 ounces of gold in compensation for Joan’s incarceration. He also agreed to accept Richard’s nephew as his heir and to marry him to one his daughters with a substantial dowry.

It was an early triumph for Richard but while in Sicily despite sharing the same bed he fell out with Philip Augustus. Their relationship wasn’t helped by the fact that Richard had rejected Philip’s sister Alys breaking off their betrothal in favour of his mother’s preferred choice, Berengaria of Navarre. He also suspected that his erstwhile lover was conspiring against him, and he wasn’t wrong.

Neither Richard nor Philip appeared to be in any rush to get to the Holy Land remaining in Sicily for six months before at last embarking again in April 1191. The fleet however was dispersed by severe storms with some of the ships being shipwrecked and their crew’s taken prisoner by the self-proclaimed King of Cyprus, Isaac Comnenus. He had arrived on the island six years earlier with a small Byzantine Army and simply taken it for himself to use as his personal fiefdom. Now he demanded from Richard, who had diverted to the island to secure the prisoner’s release, a ransom.

When Richard discovered that one of those Comnenus intended to sell like chattel was his future wife Berengaria he demanded her immediate release. The sight of an angry Richard was enough to cow most men and a terrified Comnenus was no different. He released Berengaria in haste and without further ado, but it made little difference to Richard’s desire to avenge the insult.

Comnenus had been a harsh ruler cruel in his punishments who lacked both legitimacy and popular support and when it came to a conflict with Richard, he found few who were willing to take up arms in his defence. It wasn’t long before the whole of Cyprus was in Richard’s hands. Comnenus emerged from hiding to surrender himself to Richard on the promise that he would neither be put in chains nor cast into a dungeon indefinitely. Richard felt no obligation to honour his word to such a man and so he did both. Richard then sold Cyprus to the Order of the Knights Templar.

On 12 May 1191, in the town of Limassol, Richard married Berengaria of Navarre. It was a political union and not one driven by affection, but it suited both parties very well and delighted Eleanor as the marriage secured the southern border of Aquitaine. It was not a particularly happy marriage with the couple rarely seeing one another and they were to remain childless, but Richard had married well and increased his wealth substantially. On 4 June, he set sail for the Holy Land.

Richard’s swift and decisive action on Cyprus only served to enhance his standing as a great and ruthless warrior and those in the Holy Land both Muslim and Christian aware of his reputation awaited his arrival with trepidation.

Earlier in 1186, Guy de Lusignan had become King of Jerusalem as a result of his marriage to the recently deceased Baldwin V’s sister, Sibylla. The deeply unpopular Guy was determined to assert his authority and unite the fractious Kingdom under his personal rule. The most effective way of doing this was to provoke war with the common enemy – the Saracens.

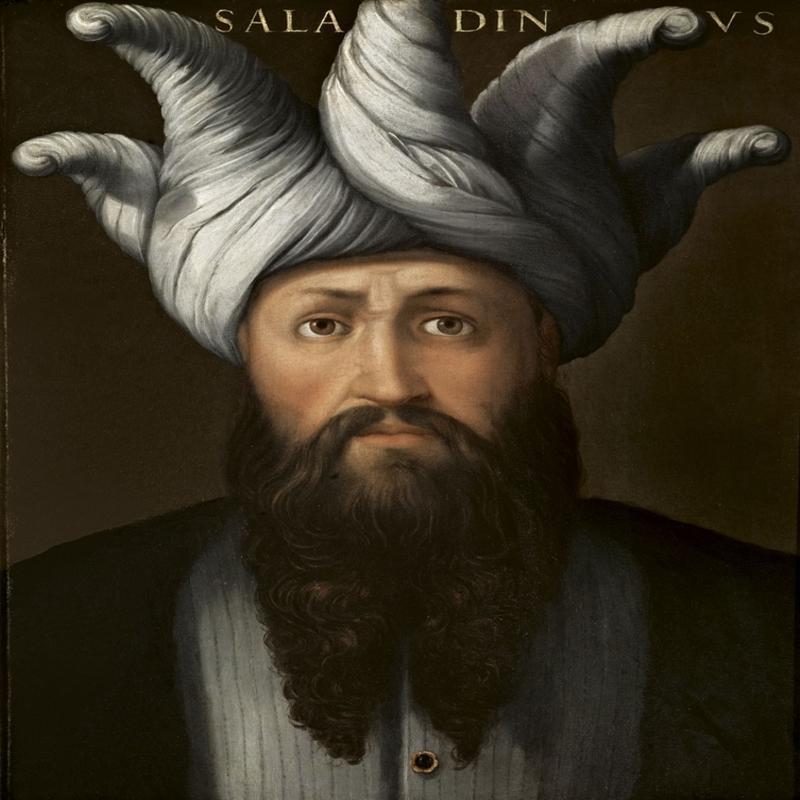

The Muslim lands that surrounded the Christian Outremer Kingdom had recently been unified under the charismatic Emir of Egypt and Syria, Salah ad-Din, better known to us as Saladin.

Guy authorised the arrogant and brutal Raynald de Chatillon to attack and pillage the caravan’s bringing spices, silks and jewels from the East and to terrorise the local Muslim populations. In the meantime, he continued to encourage the zealots among the religious orders to demand war until the cry of God Wills It became almost deafening.

The casus belli was to be the capture and subsequent death of Saladin’s sister at the hands of Raynald, and though he denied any part in her murder the rumour soon began to spread that not only had he killed her but that he had defiled and raped her before doing so. This was an insult that Saladin could not ignore and the conflict that Guy had so desperately sought was now inevitable.

It was to end disastrously when on 4 July 1187, lured into the baking hot desert by Saladin the Crusader Army went down to a catastrophic defeat at the Horns of Hattin. In the aftermath of the battle both Guy and Raynald were taken prisoner where Saladin sparing the life of the King personally slit the throat of Raynald. Following the victory at Hattin, Saladin took his time to re-group before sweeping on towards Jerusalem.

The city had been left in the control of Balian of Ibeln and despite the fact almost all the Christian knights had been killed in the slaughter at Hattin and he had little with which to defend the city he refused to surrender it and instead held out for a negotiated settlement. After an unsuccessful attempt to storm its walls, Saladin agreed.

Unlike the massacre that had occurred when Jerusalem had fallen to the Crusaders eighty years earlier on 3 October, those Christians who could afford to buy themselves out of slavery were permitted to leave the city unmolested.

It was a great personal triumph for Saladin, and he now set about eliminating the Christian presence in the Holy Land and one by one the Crusader strongholds fell to his army with most surrendering without a fight until only the port of Tyre still held out. Here Saladin was to be thwarted by the heroic defence of the city led by Conrad de Montferrat.

Not taking Tyre was a serious setback for Saladin for it left the Christians a foothold in the Holy Land and a place of disembarkation for any future Crusader Army. Indeed, Conrad de Montferrat even had the audacity to take his small army and besiege the Muslim held port of Acre.

Richard arrived at Acre on 8 June 1191, and immediately set about taking control of military operations much to the chagrin of Conrad and those others present, and this despite being sick for much of the time and having to be carried around on a stretcher.

The arrival of Richard and Philip Augustus saw Saladin withdraw his army. The dispirited defenders of Acre now negotiated the surrender of the city to Conrad to avoid a massacre and more than 2,700 Muslims were thrown into dungeons to await ransom.

The standards and banners of the various Crusader leaders now flew triumphantly from the walls of Acre but beneath the veneer of success they were already falling out among themselves. Richard argued violently with King Leopold of Austria over who was of superior rank and this arrogance in seizing Cyprus without consulting anyone else. Following the row Richard ordered his troops to throw Leopold’s standard into the moat. In a state of high dudgeon Leopold left Acre immediately. It was an event that was to have serious implications for the future.

Leopold’s departure was followed soon after by Philip Augustus who found Crusading too great a hardship and feigning illness, he set sail for Europe no doubt greedily eyeing Richard’s French dominions as he did so. There love affair had long since soured in large part due to Richard’s guilt regarding his homosexuality and he had more than once done penance for what he perceived as the sin of sodomy. Roger of Howden, an English diplomat who accompanied Richard on the Crusade and later recalled his experiences wrote of how a hermit had told Richard:

“Be thou mindful of the destruction of Sodom and abstain from what is unlawful and sinful, and that Richard having received absolution returned to his wife whom he had a long time not known, and putting away all illicit intercourse, he remained constant to his wife and the two became flesh.”

Richard agreed to release the Muslim captives held at Acre in return for a ransom of 200,000 bezants and the quid-pro-quo release of 1,500 Christian prisoners, but he also made any agreement conditional on the return of the One True Cross captured at the Battle of Hattin. Saladin was indifferent to the payment of any ransom and the release of the prisoners, but he understood the symbolic value of the One True Cross and had no intention of returning it. The negotiations dragged on with no prospect of any deal being done, Richard, eager to begin his Crusade in earnest lost patience and in a fit of temper ordered the hostages executed. Bound and dragged from the dungeons in small groups they were hacked to death, the killing took two full days.

Saladin’s prestige had been seriously damaged by the loss of Acre for though he had made good on his promise to re-capture Jerusalem he had also vowed to rid the Holy Land of the Infidel and in this he had failed. Now the Christian Infidel had been reinforced and had a formidable new leader. Saladin’s apparent abandonment of the Muslims held at Acre to their fate only did his reputation further harm. His unification of disparate Islam had been a remarkable achievement but sustaining it relied upon continuing success and almost immediately the criticism began.

Despite the fact that little remained of the Outremer Kingdom in the Holy Land other than the port cities of Tyre and Acre and the thin strip of shoreline that joined them, the political ambitions of those Christian knights still present remained undimmed.

Guy de Lusignan had been released from captivity by Saladin in 1188. This wasn’t an entirely magnanimous act on his part for he knew full well that Guy was a divisive figure who would not willingly relinquish power and that the Franks had more competent leaders they could turn to in his absence. The Christian camp was thrown into even greater confusion when Queen Sybilla died in July 1190 and Guy, whose authority had derived from his marriage, was forced to step aside for the new Queen of Jerusalem, Sybilla’s half-sister Isabella.

Many ambitious noblemen now vied for her hand in marriage, but it was to be Conrad de Montferrat she wed in November 1190. He was now King of Jerusalem but refused to be crowned as such until he had the full support of the nobility many of whom remained allied to Guy de Lusignan. This was the confused political situation that Richard encountered upon his arrival in the Holy Land, and he was quick to exploit it.

As he had been born in Poitou and owned lands in both Normandy and Anjou, Guy was a vassal of Richard’s and so he opted to support his claim to the throne. He was also a man he thought he could manipulate. However, on 26 April 1192, a Council of Barons formally elected Conrad de Montferrat as King of Jerusalem. Seeing that the tide of opinion was against him Richard abandoned Guy compensating him with the Island of Cyprus, even though he had already sold it to the Knights Templar.

Two days after he had been confirmed in his role as King of Jerusalem but before he could be crowned Conrad was assassinated almost certainly on the orders of Richard who now found himself the most powerful man in the Crusader Kingdom.

In August 1191, Richard had resumed the Crusade by leading his army towards Jaffa, a port he had to capture to protect his lines of communication before advancing on Jerusalem.

Richard had learned the lessons of Hattin and avoided leading his army inland instead choosing to march them along the coastline. His left-flank was therefore protected by the sea and his troops could be cooled by the sea-breeze and re-supplied by the fleet that sailed offshore. He also rested his troops regularly to prevent heat exhaustion.

From the outset of their advance the Crusader Column was constantly harassed by the mounted archers of Saladin’s army. They would appear without warning, unleash a volley of arrows, and then disappear again just as swiftly as they had come. At night they raided the Crusader camp but Richard who had earned a healthy respect for the fighting qualities of the Saracens in a series of earlier minor engagements maintained the discipline of his troops and refused to allow them to pursue their attackers.

Saladin had hoped to lure the Crusader’s into breaking ranks but had been unable to do so, he had also tried to stymie their advance by adopting a scorched earth policy destroying all shelter, crops, and livestock in their path and poisoning the wells but Richard’s fleet sailing offshore had made this strategy largely ineffective. Wary of Richard’s abilities as a soldier Saladin was reluctant to commit his army to an all-out assault but it was becoming increasingly evident that he had little choice. If so, then it would be at a place of his choosing.

At Arsuf on 7 September 1191, Saladin ordered his army to attack in force what he perceived to be weak spots in the enemy’s dispositions hoping to split the Crusader column into small sections that he could then eliminate in detail. Richard likewise understood the necessity of keeping his army intact against a numerically superior and more mobile enemy.

For hours the Franks laboured in the scorching sun and intense heat of the desert terrain to resist the Saracen onslaught. Their heavy armour so painful to wear in the conditions was proving its worth against the constant rain of arrows and other missiles. Nevertheless, the pressure was intense especially against the Knights Hospitaller to the rear of the column.

Somehow in the frenetic fighting Richard had managed to keep his English and Norman knights relatively uninvolved with the aim of counterattacking when the Saracens began to show signs of exhaustion and the ferocity of their assault began to wane though as the casualties began to mount especially among the horses some began to doubt his capacity to do so. At last, late in the afternoon he ordered the advance.

The Saracens for so long on the offensive were shocked at the ferocity of the attack and began to waver and flee the field. Saladin managed to briefly rally his troops even entering the fray himself but as the Frankish advance continued to gain momentum they were once more forced into flight.

Saladin’s Army managed to extricate itself from Arsuf relatively intact, but casualties were high with as many as 7,000 men killed. Richard had lost only around 700 men and it was said that in the immediate aftermath of the battle he “pursued the Turks with a singular ferocity” so violent and merciless that it was not readily forgotten.

The real impact of Arsuf was that it dented Saladin’s reputation as the invincible warrior and more importantly made him doubt that he could defeat Richard in battle. He now abandoned those fortresses remaining in Richard’s path and withdrew to Jerusalem.

Saladin doubted that if attacked he could successfully defend Jerusalem or even hold out long enough to be relieved by reinforcements from Egypt. He was advised to withdraw and abandon the city and that once having done so he could seek to lure the Crusader army from Jerusalem and destroy it in the desert as he had done at Hattin, but Saladin knew that his prestige in the Muslim world rested on his reputation as the man who had re-captured the Holy City for Islam. He could not abandon Jerusalem and he would defend it at all costs.

By late November 1191, Richard’s army was camped just six miles from Jerusalem. Some among the Franks, particularly the French contingent, wanted to continue the advance and assault the city at once but the conditions were against them. The weather had turned, storms were frequent, the temperature at night was freezing almost beyond endurance and the heaviest rainfall seen in years had turned the ground into a quagmire.

Richard was unconvinced that any attack could succeed without at least a preliminary siege and bombardment of Jerusalem’s walls, but he had no siege engines. Also, he had been advised by those knights who had been in the Holy Land for many years that even if he did take the city, he had neither the manpower nor the resources to hold it, and many of his troops were effectively pilgrims who had no intention of remaining in Jerusalem once they had prayed in the holy places. Much to the dismay of many, Richard decided to withdraw six miles further back to the town of Beit Nuba.

Unknown to Richard, Saladin’s own position was becoming weaker with the passing of every day for much like the Crusader army that opposed him his own was a coalition of forces and their morale low more and more were simply taking up their weapons and leaving.

Had Richard assaulted Jerusalem the likelihood was that Muslim resistance would have crumbled but instead he withdrew even further from the city to fortify the town of Ascalon while sending emissaries to negotiate the return of the Holy Cross and the peaceful handover of Jerusalem. Saladin who had no real intention of doing either was shrewd enough to at least show a willingness to do so. He sent his brother al-Adil to negotiate on his behalf, and to play for time.

Richard, the great Christian warrior and al-Adil the cultured man of Islam formed a relationship that surprised many. They dined together were seen to enjoy each other’s company. Indeed, so friendly were they that despite the negotiations getting nowhere Richard was prepared to offer his sister Joan’s hand in marriage to al-Adil, telling him that they could rule Jerusalem together. This wasn’t entirely an act of generosity on Richard’s part for he knew full well that al-Adil was an ambitious man, and he was hoping to cause a rift between him and Saladin.

When Richard informed Joan of his intentions however, she refused to comply telling him that she would never convert to Islam and marry a Muslim. A furious Richard raged and screamed at Joan but to no avail and she refused even to meet with him. Informed of Joan’s intransigence al-Adil likewise refused to convert to Christianity. It is uncertain whether he informed Saladin of these events before or after the agreement had fallen through.

During the negotiations Richard and Saladin had exchanged many letters where the cordiality and mutual respect between the two men was evident. Upon learning that Richard was ill with fever Saladin sent him a parcel of medicines, fresh fruit, and sherbet. Again, discovering that Richard’s favourite horse had died he sent him a fine Arabian steed as a replacement; but whereas the English King felt flattered by all the attention others within the Crusader Camp doubted Saladin’s good intentions and resented al-Adil’s presence. They feared that Richard was being seduced by the Emir’s erudite brother and that the comforts of Islam were sapping his Christian zeal and warrior spirit.

Despite the good relations that had been established between the two camps there seemed to be little prospect of a negotiated settlement and Richard withdrew back to Acre.

With little or no prospect of a positive conclusion to the negotiations Richard dealt with the outstanding issue of his de facto leadership of the Crusader cause following the assassination of Conrad de Montferrat; but no sooner had this been decided that he received bad news from England – his brother John was trying to wrest control of the country from their mother, Eleanor. The news was made even worse by the rumour that he was doing so in alliance with Philip Augustus.

Richard now had a dilemma – he had made a holy vow to return Jerusalem to God and had failed to do so but if he remained in the Holy Land there was every chance that he would lose his dominions at home. Fearing that Richard was about to depart his personal Chaplain pleaded with him to remain: “Pray consider deeply in your heart how God has honoured and magnified you in countless triumphs and successes. If you desert Jerusalem it will be the same as if you had left it to be destroyed by its enemies.”

Richard would make one more attempt to wrest the Holy City from the Saracens grasp.

In the meantime, Saladin, who had seen his grip on power weaken as a result of his failure to defeat Richard, doubted that he could any longer depend upon the support of many of his Emirs. He sought re-assurance but when he called for them in Council to pledge to defend Jerusalem with their lives he was greeted by silence. Regardless of this Saladin would remain but fearing the Crusader’s return many people now began to flee the city.

In late June 1192, Richard marched upon Jerusalem once more but distracted elsewhere and dreading the prospect of a long siege that could drag into another atrocious winter it seemed, to many in his army that he did so without conviction.

As usual Saladin’s mounted archers harassed the Crusader column on its long march, but he declined to confront Richard keeping the bulk of his army within the walls of the Holy City. Nevertheless, with the city’s defences not what they had once been and with morale in his army low he feared the worst.

As Richard’s army closed in on Jerusalem dissent arose within its ranks; some, the Burgundian contingent in particular, wanted to assault the city at once, others wanted to besiege it and await reinforcements and re-supply, while some others still, suggested that Richard detach a part of his army to attack Saladin’s Egyptian territories forcing him to divert his army from Jerusalem for its defence. Richard remained uncertain what to do.

This most valiant and decisive of Christian warriors appeared perplexed, harangued from all sides he waited and did nothing. It has been suggested that his procrastination was the result of guilt at his homosexuality, that having committed a mortal sin in the eyes of God he could not then be the man who returned Jerusalem to Christendom, and he said as much declaring he would fight in any attack upon the city but he would not lead it.

There was not a man however who did not pale beside Richard and no one else dared lead the army as long as he remained present. In late July he ordered the army to begin a partial withdrawal and it was said that as he surveyed and monitored his retreating troops from the high ground that surrounded Jerusalem, he came within sight of the city for the first time and that covering his eyes with his cloak he turned away saying, “I will not look upon that I cannot capture.”

On 27 July, whilst Richard dithered in a tactical masterstroke Saladin ordered his army to attack the port of Jaffa. If it fell it would disrupt Richard’s lines of communication and endanger his path of retreat. Saladin knew he would have to try and defend it and expected him to withdraw his army even further from Jerusalem to do so.

Richard was indeed quick to react but against expectations he did not take his entire army with him, but instead boarded ships bound for Jaffa with just 50 knights and around 1,000 men. Arriving off the coast of Jaffa he was shocked to see Muslim flags fluttering above its walls and initially believed that he was too late and that the city had already fallen but he was soon informed that the Citadel was still holding out.

On 3 October 1192, Richard departed Acre bound for England a disappointed man for despite the fact he had re-established a Christian presence in the Holy Land that had been on the verge of extinction he had failed in his vow to return Jerusalem to God. Likewise, Saladin could take little satisfaction from the turn of events. The fact that Jerusalem remained in Muslim hands was seen more as a miracle and a Blessing from Allah than it was any achievement on his part. His failure to defeat Richard in battle and vanquish the Infidel entirely from the Holy Land as he had promised undermined his authority and irretrievably damaged his reputation.

Despite the failure of the Third Crusade, Richard left Acre as the great Christian Warrior Couer de Lion - Lionheart.

He was more now powerful than he had ever been, but this only created enmity and jealousy among his rivals of whom he had many.

On 4 March 1193, less than six months after Richard’s departure an exhausted and disillusioned Saladin died of a fever in Damascus. His epic clash with Richard was to make him a hero in the West as a model of chivalry but in the Muslim world he had ruled he was soon forgotten.

Richard’s return journey to Europe was blighted by storms and bad weather. More than once he was almost lost at sea until finally the ship, he was sailing on was forced to beach near Venice. This was in territory that belonged to his old enemy Leopold, Duke of Austria, whom he had so offended during his time in Acre. Aware of this Richard and his handful of followers discarded their chain mail for peasant clothes but such was his bearing that few could be in any doubt he was a man of the highest rank. His attempt at disguise failed and Richard and his men were arrested and handed over to Leopold who could not believe his good fortune, not only was he able to humiliate his old enemy but also sell him onto the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI for a goodly sum of money.

The arrest and detention of a Crusader, a Holy Warrior of Christ, was illegal and Pope Celestine III excommunicated both Leopold and Henry as a result but the prospect of reward outweighed heavenly opprobrium.

Richard was imprisoned in Trifels Castle, but it was not a harsh confinement, and neither was he cowed by the experience telling Henry to his face: “I am born of a rank that recognises no superior but God.” He would not be released however until a ransom was paid, and it was to be a heavy one. Henry demanded 150,000 marks or 65,000 pounds of silver, the equivalent of two and a half times England’s annual revenue. In the meantime, Richard’s brother John and his new friend Philip Augustus offered Henry 80,000 marks just to keep him locked up.

John did everything he could to impede the raising of the ransom but his mother Eleanor, still Regent of England in Richard’s absence worked tirelessly on his behalf, but she was saddened by events lamenting mournfully:

“Pitiful and pitied by no one, why have I come to this detestable old age, who was ruler of two Kingdoms, mother of two Kings? My guts torn from me, my family is carried off and removed from me. The young King and the Count of Brittany sleep in dust, and their most unhappy mother is compelled to be irremediably tormented by the memory of the dead. Two sons remain to my solace, who survive to punish me, miserable and condemned. King Richard is held in chains. His brother, John, depletes his Kingdom with iron and sword and lays it waste with fire. In all things the Lord has turned cruel to and attacked me with the harshness of his hand.”

Despite her evident despair Eleanor had maintained her grip on England resisting John’s best efforts to wrest it from her. This was in part due to the fact she had the respect of the nobility who distrusted her duplicitous and mercurial son; but mostly they feared Richard’s return.

Eleanor effectively asset-stripped England and taxed it dry to raise the ransom and secure her son’s release. In normal circumstances taxation was a sensitive issue that required careful consideration before being imposed upon a reluctant people, but such was the unpopularity of John on this occasion there was little resistance. On 4 February 1194, Richard was released from his confinement and Philip Augustus hastily penned a letter to John in England:

“Look to yourself, the devil is loose.”

John soon found that there were few willing to rally to his cause and he had little choice but to surrender himself to Richard’s mercy. Brought before the King and fearing the worst he fell to his knees and cowered at his feet with tears in his eyes. Richard taking him by the shoulders raised him up and said: “There is no need to fear little brother, you are but a child.” He was in fact twenty-seven years old but then Richard’s condescending attitude towards his brother was nothing new and in any case he had no son of his own and no other heir apart from his nephew Arthur of Brittany who was still a boy.

Richard had no fear of his dribbling fool of a brother so John received no punishment just a stern warning as to his future behaviour; of more concern to him was the recovery of territories in Normandy lost to his old paramour Philip Augustus.

In 1196, he presided over the construction of his great Castle at Gaillard which was to become his obsession but war was never too distant to distract him and by early 1199 he was in Limousin besieging the Castle of Chalus-Chabrol.

In the early evening of 25 March, Richard decided to inspect the siege works but even though he had witnessed his troops come under a rain of missiles from those defending the Castle ramparts in an act of bravado he refused to don chainmail. He was an obvious target for any audacious bowman but shrugged off the many pot-shots aimed in his direction until that is one hit him in the shoulder. Carried to his tent an over-hasty attempt to remove the bolt was botched and it wasn’t long before the wound turned septic.

On 11 April 1199, aged 44, Richard the Lionheart, King of England, Duke of Normandy and Anjou, died. At his bedside was his mother, Eleanor, who had been his greatest support throughout his life.

Richard had not been a good King of England and little of benefit can be gleaned from his ten-year reign other than the motto Dieu et Droit (God and my Right) which the British Royal Family continue to use to this day.

He was instead a great warrior and a legend in his own lifetime; yet one like Attila the Hun who retired from the Gates of Rome when the city lay prostrate before him; is best remembered now for turning his face from Jerusalem at the very moment she seemed about to fall into his hands.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: