Siege of Vienna (1529): The Devil let Loose

Posted on 8th March 2021

The schismatic religious reformer Martin Luther wrote: “This be assured that the Turk is the Devil’s most evil fury.”

On 29 August 1526, the Kingdom of Hungary went down to disastrous defeat at the Battle of Mohacs to the forces of the Ottoman Caliphate under Suleiman the Magnificent. Its King was killed, more than half its territory lost and the Hapsburg Monarchy was put on the defensive.

Islam was on the march at a time when Christendom was increasingly at war with itself.

Suleiman the Magnificent had succeeded Selim I as Sultan in September 1520, aged just 25, and his reign of 46 years would usher in a period of unprecedented power and Imperial expansion – it was to be the Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire.

A scholarly man and a political reformer he was also a warrior who often took command of his own armies in the field as they annexed much of the Middle East, the Balkans, North Africa and came to dominate the shipping lanes and trade routes of the Eastern Mediterranean. He was also a man of limitless ambition who sought to conquer Rome just as the Franks had earlier captured Jerusalem – and the gateway to Rome was Vienna.

Following his victory at Mohacs and having consolidated his power in Eastern Hungary, Suleiman declared Jihad or Holy War on the Infidel and in particular the Hapsburg Empire. It was opportunistic on his part to say the very least for he knew full well that the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V could expect no help from Catholic France and its King Francis I, with whom he had recently been at war and was for a time his captive. He was also heavily engaged in trying to suppress insurgent Protestantism and its continuing spread.

Throughout March and April 1529, Suleiman mustered a vast army in Bulgaria, some 150,000 men, and though he would accompany it he appointed the Grand Vizier Pargal Ibrahim Pasha to command in his name. But the campaign that began in early May was beset with problems and dogged by ill-fortune from the outset.

Disease had already broken out in the Ottoman Camp long before they departed and the spring rains that are common in the Balkans were uncharacteristically heavy and persistent causing rivers to overflow and turning what roads there were into quagmires. Most of the heavy guns that could neither be extricated from or moved in the boggy terrain had to be abandoned and many of the pack animals, in particular the camels, died of the cold or suffocated in the mud while men wet-through, exhausted and malnourished sickened and fell by the wayside.

In advance of the main army Ibrahim Pasha had despatched his Sipahi horsemen, expert archers who could ride at pace and shoot arrows simultaneously to reconnoitre the terrain and in doing so they killed a great many people; but the worst atrocities were committed by the Akinci, irregular cavalry no less expert in the use of the bow but with the mace and the axe as their preferred weapons of choice for close-quarter combat. They would arrive at any destination a few days in advance of the army to sow terror and subdue the countryside around Vienna.

The Akinci who served for plunder and were permitted to keep what they stole would rape the women and children they seized before selling them on to the slavers who would accompany them. The men they captured would be decapitated and their heads stuck on poles to be deposited around the countryside in an act designed to spread terror and fear.

Peter Stern, a Court Official who was present throughout the siege described their behaviour: “People were butchered in their thousands with babies slit from their mother’s womb and cast aside or impaled. Maidens were violated until they died. May the Almighty have mercy on their souls, and may the murders committed by these cruel bloodhounds not go un-avenged.”

Stories of Muslim brutality were not just Christian propaganda one of Suleiman’s secretaries also kept a diary during the campaign and wrote: “Our warriors forcing their way into a farmstead and sounding the Muslim battle cry drew their sabres and cut down all, the Infidel. They seized the girls and boys and secured much booty. This too is further proof of the grace of Allah.”

The Akinci had the desired effect and those forewarned of the Ottoman advance abandoned their homes and goods and fled to the city.

The leading Hapsburg Official in Vienna, Wilhelm von Roggendorf hastily organised the city’s defences but with few troops, only 400 more men had volunteered to serve in the Militia, there was little he could do. He prayed for reinforcement, if it did not materialise then the city would fall.

As both King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V was hard-pressed. Not only did he have to guard against a France that sought to be the leading power in Europe and was willing to make alliances with the enemies of Christendom to achieve its end. He also had to contain the fall-out from the Reformation and try to wield some control over the fractious German Princes. Now he had to contend with the threat from the East. He could neither spare the time to be at Vienna in person nor could he commit his army to its defence - but he would reinforce its garrison. He despatched some 3,000 Spanish Arquebusiers and 14,000 Landsknecht mercenaries to be deployed to the city. They arrived in the nick of time but now behind its high walls and with a garrison of 21,000 men Vienna at least had a chance of survival.

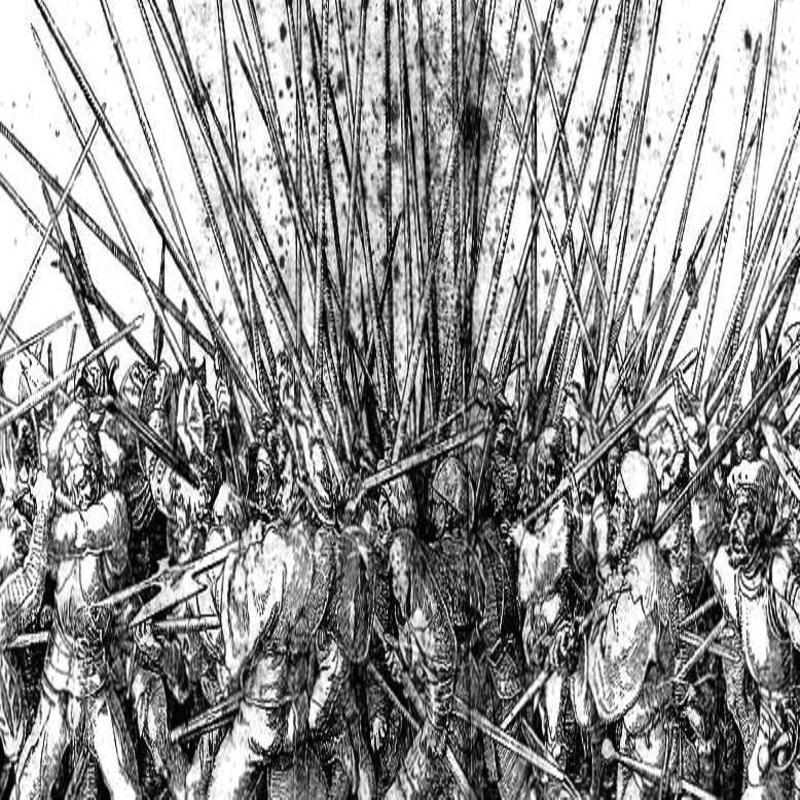

Although they were mercenary soldiers recruited mostly from Alsace, the Rhineland and the Tyrol who owed no loyalty except to their purse the Landsknecht were disciplined, professional and some of the finest troops in Europe. They were much sought after, and they knew it. Arrogant and thuggish they lived life with a swagger and were often as feared by the populations they were there to defend as they were the enemy. They dressed flamboyantly, wore the latest armour and liked to flout social convention. Their codpiece for example, was designed in the shape of an erect penis to indicate their virility. But they were no show ponies they could fight even if their willingness to do so was driven by the size of the prize and booty on offer. To ensure their loyalty Vienna melted down its treasure to produce gold and silver coin.

They fought in formation mostly as pikemen but were also armed with the Zweihander, a sword with a blade 6 ft long, and were expert in wielding the halberd. One-in-four of them would be a musketeer or arquebusier, and they were trained to make the best use of fortifications.

By late September 1529, the Ottoman Army stood before the walls of Vienna and its encampment made for an impressive sight, but this only served to conceal a multitude of problems for although its march west had been virtually unopposed the weather had barely improved ensuring that much of their baggage would be lost en-route leaving them short of supplies. Also, around a third of the men were sick from disease and too ill to fight. They also had a great many cavalry not suited to siege warfare and few if any heavy guns which only weakened their position even further.

Suleiman knew he could not sustain a prolonged siege and so needed a quick victory. He also wanted Vienna’s riches for himself and was aware that if its defenders resisted and he was forced to storm the city then according to Islamic Martial Law he would have to grant three days of pillage and plunder.

Having arrayed his army in a manner that displayed its strength Suleiman sent three unharmed prisoners to Vienna with his demands:

“To the Commander and the other inhabitants of the fortress of Vienna let it be known, that if you become Muslims nothing will happen to you, but if you offer resistance then by Allah, the most sublime, your city will be reduced to ashes and young and old slaughtered.”

Suleiman felt sure that the mere sight of his army would be enough to intimidate the garrison into surrender, but his troops had already done him a disservice. The brutality of the Akinci had guaranteed that no promises of fair treatment would be believed, and the people were not just terrorised but desperate not to fall into Turkish hands.

When Nicholas of Salm chose to not even respond to the Sultan’s demands let alone indicate a willingness to negotiate he met little resistance.

Without heavy siege guns there was little prospect of Vienna’s defences being breached in a hurry, but Ibrahim Pasha reassured Suleiman that mines placed beneath its walls would soon bring them down leaving those cowering behind them defenceless against overwhelming odds.

As the Turks busied themselves digging trenches so the sappers would have a place of cover from which to work the rain returned and it did not cease for two whole days. As long as it rained Vienna was safe for no sooner were the trenches dug than they filled up with water.

The incessant rain was scuppering Ibrahim Pasha’s best laid plans. Not only were the sappers spending more time bailing out their trenches than digging tunnels the black gunpowder awaiting detonation became soaked and useless. The Ottoman Camp was despondent: “It is a bitter cold day and night, and impossible to describe how much rain fell.”

The small cannon the Ottomans had brought with them, designed to fire not at the walls but over them and into the city, were also rendered ineffective by the quagmire as the citizens of Vienna tore up the hard cobbled streets allowing the cannon balls to simply land and sink into the mud.

When the rains at last ceased and the ground dried the tunnelling resumed just as the defenders knew it would and so as the sun rose on 3 October, some 2,000 Landsknecht attacked the Turkish trenches to find the explosives. They failed to do so but they did return with a prisoner who was immediately ‘put to the question.’

The Viennese had little time to waste, and the torture was thorough and brutal. It was not long before he revealed what he knew: “When he was put to the question the man finally admitted that charges had been placed to the left and the right of the Carinthian Gate. No one had any previous knowledge of this. When our troops were informed they filled basins with water and placed guards.”

What the hapless prisoner had revealed was not detailed enough to launch another assault but with the basins strategically positioned ripples would appear on the surface of the water telling them where the digging was taking place. The longer the Ottomans had to wait before they could detonate their mines the greater became the likelihood of their detection, and so it had proved.

Having discovered where the Turks were tunnelling on 6 October, Nicholas von Salm ordered the Landsknecht to sally forth once more and 8,000 men swords drawn attacked where the sappers were digging cutting down many before Turkish troops could come to their support. But at the end of a bloody encounter which in the confined space of the trenches saw swords abandoned for knives and clubs they failed to locate the tunnels or seize the gunpowder.

The final assault began early on 14 October, as a misty squall shrouded the city and snow began to fall. Amid the blowing of horns and the shouts of the attackers could be heard the thunder of guns but despite the rich rewards on offer to those who captured the city there was more sound than fury.

Despite the fighting lasting over two hours and evermore troops being funnelled into the attack more insults were exchanged than blows struck. Peter Stern described the final moments of the siege: “The enemy mounted a fierce (last assault) but the storm soon abated. Enemy losses amounted to about 350 dead. On our side just one Hispanic was shot and numerous wounded – Praise the Lord!”

Muslim fighting spirit had been broken and that night they began to abandon their camp.

The defenders of Vienna had suffered around 4,500 casualties during the siege, the Ottomans some 15,000 but they were to lose many more during a retreat that soon turned into a nightmare.

As they began their march east the rain fell harder than ever, and the temperature dropped even further. With pack animals few and far between baggage and supplies had to be abandoned, wagons unable to move in the mud would remain stranded and with swollen rivers to cross the booty that weighed them down had to be left behind. Many froze to death or drowned, others died of starvation and disease.

In one of the last entries in his diary the man who was a Secretary to the Court of Suleiman the Magnificent wrote: “It rained incessantly from dawn to dusk, some of the soldiers lost their entire equipment in the endless deluge and many men along with their horses sank and drowned in the mire. The suffering was indescribable.”

Suleiman’s ambition was not dimmed by his humiliation before the Gates of Vienna, and he held onto his vision of conquering the West but it wasn’t to be distracted as he was by his on-going conflict with the Shia Muslim Safavid Dynasty in Persia for dominance in the East. Neither would Charles V again be taken unawares maintaining a formidable military presence in Bohemia thereafter.

As for the Landsknecht their reputation soared after the siege, but it was a fame that would not be enjoyed by their Commander Count Nicholas of Salm who injured during the last days of the fighting would die in May 1530, of his wounds.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, War

Share this post: