Sir Roger Casement and the Black Diaries

Posted on 30th June 2021

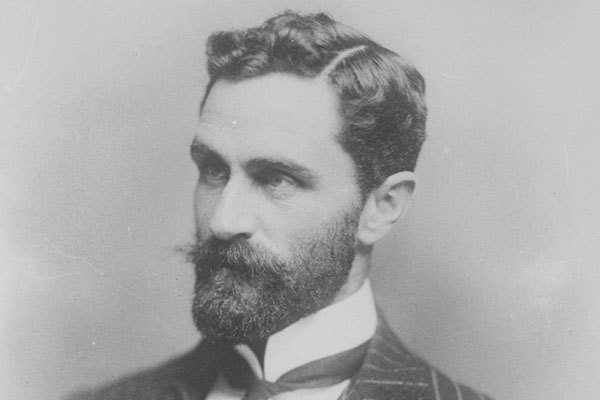

For more than thirty years Roger Casement was known as a sober, diligent, hard-working representative of the British Government admired throughout the world for his humanitarian work on behalf of the poor and dispossessed in South America and on the African Continent. Upon his retirement he received a knighthood, numerous other awards, and it seemed he could look forward to a golden sunset. Just four years later he was hanged for treason.

Roger David Casement was born in Sandycove, Dublin, on 1 September 1864 to a father who was a Captain in the British Army and always short of money, and a mother who had him secretly baptised a Catholic against his father's wishes.

When Roger was nine years old his mother died, and he was sent to Ulster to be raised by his Protestant relatives. He attended school in Ballymena where by all accounts he was a good student but his education was cut short when he left at the age of sixteen to take up a clerical position in the Liverpool shipping company, Elder Dexter. His work for them took him to the Congo Free State with whom the company had strong commercial ties.

His work in the Congo, which went way beyond his remit of merely tying up deals for his employers, impressed a great many people and in 1882 he joined the British Foreign Office very soon becoming one of their most distinguished diplomats. He was appointed British Consul in Mozambique from 1895-98 and in Angola from 1898-1900.

In 1901 he was sent back to Boma in the Congo where he was commissioned to conduct a study of the human rights abuses that were reportedly taking place there.

At the time the diamond rich Congo was the personal fiefdom of King Leopold I of Belgium but Casement's subsequent report highlighting the appalling exploitation of labour and the terrible atrocities that were being committed against the native population was so scathing in its summing up that it caused outrage throughout the world and forced the Belgian Parliament to act. The Congo was removed from Leopold's control and in future it was to be run by the Government itself.

In 1906 Casement was appointed British Consul-General in Rio de Janiero where he immediately launched an inquiry into the mistreatment of the Putumayo Indians in Peru. His work led to there being a number of arrests and a general improvement in conditions.

Upon his return to England, he worked for the anti-Slavery Society and it was for this along with his other humanitarian endeavours and time as a dedicated public servant that he was knighted by King George V in 1911. The following year he retired from the Diplomatic Service on the grounds of ill-health.

Casement had always been a firm supporter of Irish Home Rule and as a young man he had campaigned for the Irish Nationalist leader Charles Stuart Parnell, but he later suppressed any public advocacy of it for the sake of his career.

During the early months of 1914, Ireland descended into chaos as the argument over Home Rule saw both Catholic and Protestant form militias in the expectation of civil war. To diffuse the situation, it seemed that the British Government would at last have to act and a Home Rule Bill was in the advanced stages of completion when the Great War broke out and it was peremptorily shelved for the duration.

Yet again, the Home Rule issue had been brushed aside by events and the sense of betrayal particularly among more moderate nationalists was great and many now began to look beyond Home Rule to outright independence. Casement, a fervent Home Ruler was bitterly disappointed.

Still, war or no war Ireland remained a divided country. The Six Counties that formed Ulster in the north were predominantly Protestant and opposed to any weakening of the Union with Britain and even in the south of the country which was almost entirely Catholic enthusiasm for the nationalist cause was far from universal and during the First World War 150,000 Irishmen were to volunteer to fight for Britain, most of them Catholic. Even so, nationalism was on the rise and those who did support it were dedicated and determined.

In retirement Casement was busier than ever helping organise the Irish Volunteers, the armed nationalist response to the formation of the Protestant paramilitary Ulster Volunteers.

In July 1914 he travelled to the United States to raise money for the nationalist cause and when war broke out immediately contacted the German Ambassador to try and elicit their support for Irish independence. The Germans were certainly interested in the possibility of opening up a second front against the British but didn’t want to become directly involved. Nonetheless, in October he sailed for Germany.

Despite Casement's best efforts the Germans remained non-committal, they would support an Irish uprising but not with troops and a German Army would only land on the shores of Ireland at the invitation of a friendly Government. They did however make a public declaration of support.

In the meantime, he busied himself with trying to raise an Irish Brigade from among British prisoners-of-war, but this proved to a dismal failure. Despite the failure to make good on his promise to recruit Irishmen for the cause Casement continued to harangue the German Government until in April 1916 they agreed to provide him with 20,000 rifles, 10 machine guns and ammunition. Considering how hard he had worked it didn’t amount to much. A little later he learned of the planned Easter Rising.

Because of his reputation as a pillar of the British establishment he was not entirely trusted by the leadership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B) who often kept him in the dark as to their plans.

He believed that the rising was premature, foolhardy and doomed to failure and he was desperate to get back to Ireland and convince them to cancel it at least until a time when a German victory appeared likely, or they could rally sufficient support internationally particularly in the United States.

The arms he had been promised were hastily loaded onto the merchantmen Libau while Casement himself would travel on the submarine U.19.

The Libau was intercepted off the coast of Ireland by the British destroyer Bluebell and the arms were never landed. Casement however had already been put ashore in the early hours of 21 April at Banna Strand in County Kerry.

Weak through ill-health he could not walk far and had to hole up nearby, but he had been seen and it was not long before his presence was reported to the local police, and he was arrested.

Because of his high-profile he was quickly transferred to London and imprisoned in the Tower of London where, following the crushing of the Easter Rising that he had so vehemently opposed he was charged with espionage and treason.

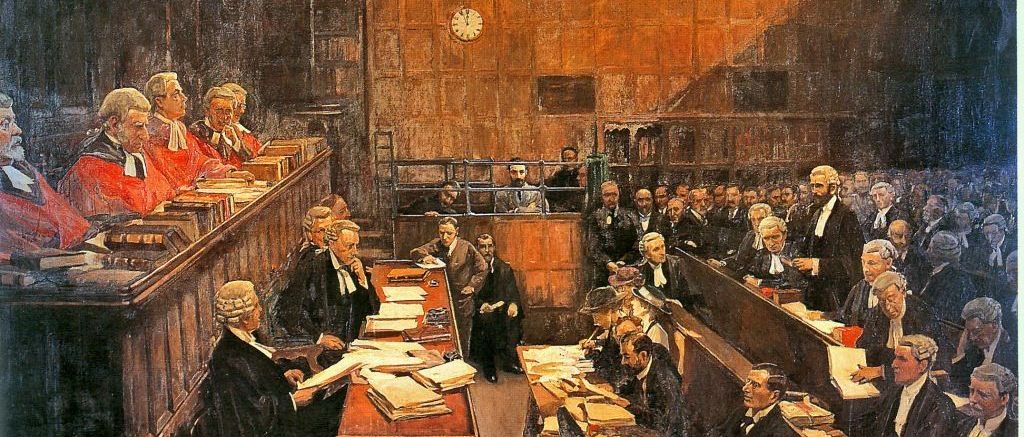

His subsequent trial caused a sensation and split public opinion: to some Sir Roger Casement was a Knight of the Realm, a renowned humanitarian and the good face of Empire; to others he was the worst kind of traitor, a man who had reaped all the benefits that his country could offer him only to betray it at a time of war.

Casement’s prosecution was not as clear cut as it at first appeared. The crime of which he was accused had been committed abroad outside British jurisdiction so he had to be tried under a treason statute dating back to 1351.Casement’s defence was that as an Irishman he could not be justly tried in an English Court at all.

Arcane legal arguments aside his guilt it seemed was never in doubt and on 26 June 1916, the jury took little time to find him guilty, before sentencing was passed Casement was permitted to address the Court: “What is the fundamental charter of an Englishman’s liberty? That he shall be tried by his peers. With all respect, I assert that this court to me, an Irishman is a foreign court – this jury is for me, an Irishman, not a jury of my peers.

It is patently obvious to every man of conscience that I have an indefeasible right, if tried at all under this statute of high treason, to be tried in Ireland, before an Irish court, and an Irish jury.”

His words were widely viewed as being disingenuous at best and hypocritical at worse.

Casement immediately appealed the death sentence and a campaign for clemency now began that was supported by the Catholic Church and writers such as H.G Wells, George Bernard Shaw and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Even the King indicated that he approved of clemency. The novelist Joseph Conrad who had a son serving on the Western front thought otherwise however and said so - Casement should hang for his treason.

The campaign for clemency appeared to be gaining momentum and those in the Military who wanted to make an example of Casement feared that his sentence would be commuted to life imprisonment or perhaps even house arrest or release under licence. In response, Reginald "Blinker" Hall, the Chief of British Naval Intelligence began to circulate to prominent people extracts from what soon became known as the Black Diaries. These appeared to show that Casement was a promiscuous homosexual who had diligently recorded his many sexual encounters with young men. The diaries were heavily coded but even so the tenet of them appeared clear:

“Sunday 4 December. Very hot - looking out window saw Ignacio waiting. Joy. Off with him to Tirotero and Camera. Bathed and talked and back at 11.00 gave 4/-.

“At 5.30 Cayamarca Policeman till 7 at Bella Vista and again at 10.30 passeando and long walk. Tall Inca type and brown."

“Left Carlton and to London. Greek boy fled”.

Entries such as these were numerous, and they shocked a socially conservative Britain where homosexuality was still illegal and punishable by imprisonment and hard labour. To many they verged on the pornographic.

The existence of the Black Diaries soon became public knowledge and opinion which had been divided if not as to his guilt, then as to the most suitable form of punishment began to turn against him. Many of those who had previously campaigned so hard for clemency were no longer willing to speak up on his behalf. They could forgive his treason but not his homosexuality, nor the way he chose to satisfy his yearning.

It was suggested by some that the Diaries were fake or had been tampered with to put Casement in the worst possible light, but few people were any longer willing to listen.

Sir Roger Casement had been condemned not just as a traitor to his country but as a sexual predator, who preyed on young men to satisfy his sordid sexual desires even paying for his sodomy - the evidence of his sleaze written in his own hand.

Stripped of his knighthood plain Roger Casement was hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August 1916.

In 1965, Roger Casement’s remains were repatriated to Ireland and given a State Funeral attended by the President Eamon de Valera, a veteran of the 1916 Easter Uprising that he had been so desperate to forestall.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: