Somme Battle: The First Day

Posted on 26th January 2021

Now God be thanked who has matched us with this hour and caught our youth and wakened us from sleeping.

(Rupert Brooke)

Britain’s small professional army which had been trained for home defence and to police its Empire never intended to engage in a major European War. Yet in August 1914 along with Reservists and Territorials it would form the British Expeditionary Force to France. Despite being dismissed by the Kaiser as that contemptible little army it had during the bitter struggles of 1915 proved its worth, but its manpower resources were never sufficient to the task that confronted it.

By 1916 its ranks were so diminished that what remained of the ‘Old Contemptibles’ would be absorbed into and form the core of a new volunteer ‘Citizen Army.'

The Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener knew the British Army was in no position to engage in a major conflict and had immediately called for 100,000 volunteers to supplement the regular forces. His appeal was to produce the iconic image of a stern Kitchener staring out from a poster, pointing his finger, and demanding Your Country Needs You!

In the first flush of patriotic fervour the response to Kitchener’s call to arms far outstripped expectations as the prospect of fighting for King and Country, the lure of adventure and the opportunity to escape the grinding poverty that blighted so many lives proved irresistible.

The recruitment campaign was everywhere to be seen on billboards, on the sides of buses and trams, in railway stations and shops as large rallies were held in every major town and city. Those attending sporting events were called upon to join the colours, Boer War veterans addressed working men’s clubs, priests called for volunteers from the pulpit and if all this failed to stir the blood then there was always the fear of being perceived a coward by the fairer sex.

The recruitment campaign received a further boost with Lord Kitchener’s promise that those who enlisted together would serve together. This propaganda coup that would prove such a battlefield tragedy saw the emergence of the so-called Pals Battalions. Units such as the Public Schools Battalion, the Stockbrokers Battalion, the Artists Battalion, the Glasgow Tramways Battalion, the Warehousemen and Clerks Battalion, the London Cyclists, the Salford and Accrington Pals and many others were formed. Of the 1,000 or so Volunteer Units raised in the first two years of the war some 70% could be described as Pals Battalions with entire football teams, factories, fishing fleets, and even the households of the great landed estates enlisting. There was to no lack of enthusiasm for taking the King’s shilling.

In the first month of the war alone 500,000 men enlisted in the ranks with many more rejected on health grounds and even after the passing of the Military Service Act in January 1916, and the introduction of conscription of the 6 million British men who served in World War One more than 50% volunteered to do so. This was Kitchener’s Volunteer Citizen Army, enthusiastic, inexperienced, and still only partially trained it would bear the brunt of the fighting on the Somme.

The British Commander on the Western Front since December 1915 had been General Sir Douglas Haig, a lifetime soldier who had great confidence in his men but even so doubted the preparedness of this new Volunteer Army to undertake major operations as early as August 1916 as was planned. Now it had been brought forward a month those doubts were brought into even greater focus. He expressed his concerns to Kitchener who asserted that the offensive must go ahead regardless - the pressure on the French at Verdun determined that it must.

The offensive in Picardy had originally been intended as a predominantly French affair with British support but a renewed German assault at Verdun in late May meant that the French could spare only 5 Divisions and so would take responsibility only for the southern end of the line adjacent to the River Somme. So, it would fall upon the British with 14 Divisions to advance across the open farmland to the north with 66,000 men in the first wave.

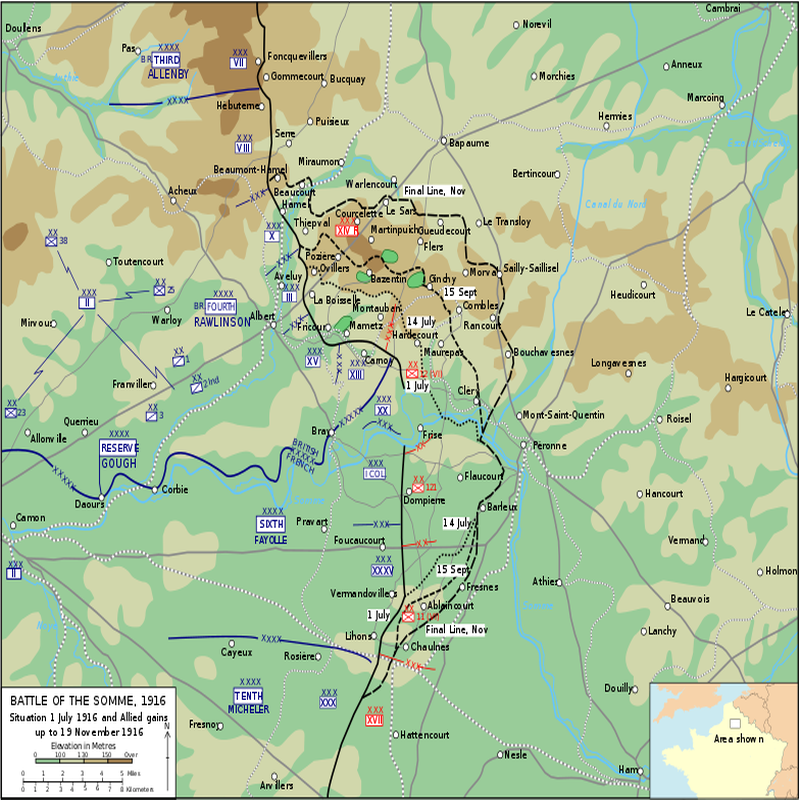

Their objective was a series of fortified villages beyond the German front-line trenches - Pozieres, Montauban, Mametz, Fricourt, La Boiselle, Ovilliers, Thiepval, Beaumont Hamel, Serre, and Gommecourt. These villages they planned to take on the first day of the attack leaving the way clear for the cavalry held in reserve to advance down the old Roman Road and take the town of Bapaume sweeping up the remnants of the German Army as they went. The British would then push onto the German second-line defences already weakened by the heavy and sustained bombardment that would have preceded their advance.

The responsibility for the offensive would fall to the 400,000 men of the Fourth Army under the command of General Sir Henry Rawlinson, a Boer War veteran who had previously served as a Staff Officer in the Sudan but had never before commanded such a large army.

A cautious man by nature he disagreed with General Haig over the objectives of the offensive believing them to be too ambitious and preferring a more piecemeal approach, but he did not depart from the plan and expressed his confidence in its success.

On 24 June, 1,537 British and 100 French guns opened fire on the German first and second line trenches. The bombardment, the most intensive ever known was so ferocious that on a clear day the thunder of the guns could be heard as far away as London and few who witnessed it believed anything could survive under such a hail of shells.

It was a view shared by General Rawlinson who reassured Haig and others that nothing could exist at the conclusion of the bombardment in the area covered by it. But unlike the British trenches that were often little more than narrow slits in the ground designed as advanced lookout posts or assembly points for attack the Germans determined to hold onto French territory captured early in the war had constructed their front-line for defence with reinforced concrete bunkers dug deep into the hard chalk terrain sometimes as much as 30 feet beneath ground, and these bunkers were to prove almost impervious to a bombardment that for all its sound and fury terrified more than it killed and destroyed.

There were also too few heavy guns and far too many shrapnel shells effective against attacking formations but worse than useless against fixed positions or for cutting barbed wire. Also, up to 30% of the shells failed to detonate on impact. Indeed, the Germans were later to put up signs mocking the British - would you like us to return your unexploded shells?

The bombardment that had seen a field gun for every 20 yards of front fire some 1.7 million shells at a rate of more than 3 a second and was intended to cut the barbed wire, destroy the German fortifications, and eliminate their artillery had failed to achieve any of its objectives. But for those Germans subjected to it, it had been hell. Trapped underground for the entirety of the bombardment, short of food and water, unable to sleep, terrified as their shelters shook and the earth trembled beneath them, with nerves shredded and driven mad by the constant roar of the guns and the shrill whistle of the shells as they passed overhead before thundering into the ground, they nonetheless endured it in relative if uncomfortable safety.

Dawn on the 1 July was a warm morning with barely a cloud in the sky above to interrupt the glare of the sun as a thin mist hung low over no-man’s-land. As they tucked into their breakfast of bacon, biscuits, jam, tea, and a tot of rum the British Tommy was eager to do his bit at last, but they were also apprehensive for despite reassurances of the advance being a walk-over many of them on their march to the front had seen the mass-graves which had been dug in preparation for the casualties to come, and the few hundred yards that separated the opposing front-lines in many places now seemed an awful long way. But then had they not been told time-and-time again that there would be no Germans, that they would encounter only dead bodies.

No one could know for sure, and the to-and-fro of the banter laced with a soldiers black humour would often be followed by long periods of silence as they waited for their Officers, some barely out of school, to check their watches, blow their whistles, and order them over-the-top. Still confidence remained high, and few Officers doubted the spirit of their men and their willingness to make the sacrifices required for victory. Lieutenant Roland Ingle of the 7th Lincolnshire Regiment wrote in his diary the night before the offensive was due to begin:

The men who are going to be knocked out in the push, there must be many, should not be looked upon with pity because going forward with resolution and braced muscles puts a man in a mood to despise consequences. He means to dish out more than he gets and a man used to sports takes things even in the great chance of life and death as part of the game.

Lieutenant Ingle’s words summed up the public-school spirit that infused so many of those young Officers leading their men into battle for the first time, and also like so many of them he would be killed in the opening moments of the attack.

Corporal Arthur Hubbard of the London Scottish writing home to his parents on 29 June adopted a more sanguine tone:

I hope we will be successful on Saturday morning, 1 July, at dawn when you are all asleep, in driving the Huns out of their positions and without any bad luck to myself. I have to go over with the first batch. I should be in my glory if the news came through to cease firing and pack up. I can imagine how everything looks at home, and the garden, as you say, must almost be at its best.

Arthur Hubbard would survive the Somme but was to suffer from shellshock and be repatriated back to England where he would later take his own life.

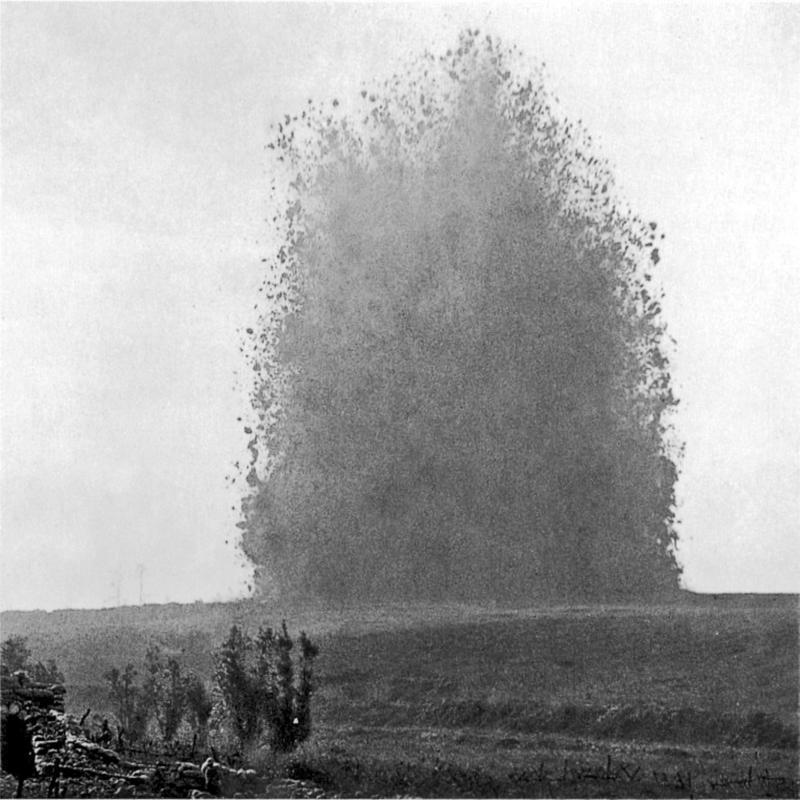

Intended to kill and confuse the enemy and provide cover for the advancing troops at 07.28 two minutes before the assault was due to begin, ten mines which had been dug beneath the German front-line trenches were to be detonated.

But the Corps Commander in the Beaumont-Hamel sector had made the arbitrary decision to detonate the Hawthorn Redoubt Mine ten minutes early so that the official war cameraman could capture it on film. He did so but at the cost of revealing to the Germans what was about to come and bringing down a retaliatory artillery barrage on the trenches from which his own troops were about to advance.

There had also been a serious breach of security the previous day when a Staff Officer of the Tyneside Scottish had radioed a good luck message to the troops revealing the day and time of the attack. The message had been intercepted by a German listening post and they now knew when the assault would begin and that mines were to be detonated. They would be ready.

At 07.30 as the debris and smoke from the exploded mines began to clear the whistles were blown and with bayonets fixed, carrying 70 lbs of kit, and ordered to walk at a steady pace in line two or three yards apart, the men scrambled over-the-top and into no-man’s-land.

At the same time emerging from the claustrophobic subterranean existence of their bunkers blinking in the glare of the sun the Germans were only too relieved that the bombardment was over and some in their enthusiasm to get at the Tommy who had made their life hell exposed themselves to danger by mounting the parapet to fire at the advancing British.

A German soldier described the scene:

At 7.30 am the hurricane of shells ceased as suddenly as it had begun, our men clambered up the steep shafts. A series of extended lines of infantry were seen moving forward from the British trenches. They moved at a steady pace as if not expecting to find anything alive in our trenches.

The bizarre serenity of those opening moments of the attack with their vivid recollections of birdsong and strolling in the warm sunlight as if along the by-ways of home were quickly shattered by the familiar rat-tat-tat of the machine gun and the booming of the German artillery as the British advanced in close order across no-man’s-land and into a hail of shot and shell. Men began to fall by the dozen as those who advanced far enough were horrified to discover that the German barbed wire had not been cut and the implements, they had been provided with were incapable of doing so. Entangled on the wire men waited for the bullets that would inevitably kill them, others sought shelter where there was none.

Attacking on the northern flank of the British line toward Serre were the Accrington Pals, part of the East Lancashire Regiment who advanced into a murderous storm of machine gun fire and grenades that saw them decimated losing 584 of 720 men, most cut-down within twenty minutes of zero hour and less than 100 yards into no-man’s-land.

A mile to the south of Serre at Beaumont-Hamel the Lancashire Fusiliers who the previous night had crept from their trenches and taken shelter in a sunken lane only some 100 yards or so from the German front-line were already under intense shell and sniper fire long before the attack began. Despite the sunken lane already appearing more like a dressing station than an embarkation point they twice tried to cover the short distance to the German trenches but were forced back with many falling just yards from the sunken lane.

Their Commanding Officer radioed his willingness to try again but the attack was cancelled by Headquarters. They had suffered 387 casualties, more than half of them killed.

The Newfoundland Regiment, a volunteer unit recruited from that small colony off the coast of Canada, did not participate in the First Wave and were waiting in their reserve trench a mile to the rear when they received the order to advance and recapture the crater that had resulted from the premature detonation of the Hawthorn Redoubt Mine and had since been occupied by German machine-gunners. Unlike the British Regulars of the Essex Regiment who were meant to accompany them the inexperienced Newfoundlanders did not use the crowded communication trench to reach the front-line but instead emerged from their positions and into open farmland. The only figures moving in no-man’s-land and huddling together as if for protection they made an easy target, and all 26 Officers were either killed or wounded as were 658 of the 726 men under their command a casualty rate of 91%. Their Divisional Commander in his official report wrote:

It was a magnificent display of discipline and valour and it failed of success because dead men can advance no further.

At Fricourt, the Green Howards had been ordered to remain in position and not participate in the First Wave but at 07.45 Major Ralph Kent in command of C Company took it upon himself to lead it forward and 103 of 140 men were cut down before they had advanced 50 yards. Major Kent who survived the attack excused his actions saying there were times when it was an Officers responsibility to anticipate events, if not it would seem its consequences.

Incorporated into the Northumberland Fusiliers the Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish were Pals Battalions recruited in the North-East of England many of whom were miners who had walked up to 15 miles from remote pit villages in their enthusiasm to enlist, and just as Lord Kitchener had promised they would serve together, fight together, and if necessary, die together.

The Tyneside Irish, with the Tyneside Scottish in close support, were ordered to advance towards the village of La Boiselle at the same time as the main attack but from the reserve trenches a mile further back.

Marching across high ground and clearly visible on the horizon they came under fire long before they reached their own front-line and with catastrophic results. Of the 3,000 men of both Battalions combined 2,909 were to be killed or wounded with fewer than 50 able to report for duty the next day.

At the northernmost tip of the line a diversionary attack was made on the village of Gommecourt intended to draw Germans reserves away from the main focus of the offensive farther south, but the fighting was no less fierce for that, and here at least their appeared to have been some initial success. The Staffordshire Regiment along with elements of the London Division including the Queen Victoria Rifles and Westminster Rifles were able not only to capture the German front-line trenches but also parts of their second-line defences as well. The Germans were swift to counterattack however and the inability of other Units to break through and lend support despite repeated attempts to do so left the defenders exposed to assault from three sides. The desperation of the fighting was conveyed in the message sent by Major Charles Dickens of the Kensington Regiment:

I have, as far as I can find, only 13 men left besides myself. Trenches unrecognisable. Quite impossible to hold. Bombardment fearful. I am the only Officer left. Please send instructions.

The assault at Gommecourt failed in its objective of forcing the Germans to call upon reserves that were urgently needed elsewhere and by nightfall they had been forced to withdraw from the gains they had made.

In the centre of the line the Salford Pals were charged with capturing the heavily defended village of Thiepval and the high ground surrounding it. They successfully stormed the German front-line trench but moving onto Thiepval they were mercilessly cut down by more than 30 strategically positioned machine guns. Of the 674 Salford Pals who attacked Thiepval, 470 became casualties.

Just to their north the Ulster Regiment had succeeded in capturing the Schwaben Redoubt but after many hours of savage and often hand-to-hand fighting they had been forced to withdraw leaving behind more than 700 dead and wounded.

And when the summons in our ears was shrill, unshaken in our trust we rose and then flung but a backward glance and carefree still went strongly forth to do the work of men.

So wrote Lieutenant William Noel Hodgson, 9th Devonshire Regiment, killed in action, 1 July 1916.

Captain Duncan Martin of the East Devonshire Regiment, an artist and geometry teacher in civilian life had returned to England prior to the offensive with something on his mind, a German machine gun positioned beneath a stone crucifix in a cemetery near the village of Mametz he was convinced would reap havoc with his Battalion in any advance and he made a plasticine model of the area to prove it. Upon his return to the front-line he showed this model to his Superiors explaining the mathematical inevitability of what he was suggesting. He was told not to speak of his findings and reminded that the bombardment was guaranteed to remove any such obstacles. On 1 July, Captain Martin was killed by the German machine gun positioned under the crucifix in the cemetery at Mametz.

Despite the death of Captain Martin and most of the other Officers in his Battalion the attack by the Devonshire's at Mansell Copse was to prove one of the few successes of the day, and the resting place of those killed is still located there where an inscription made on a stone cross read: The Devonshire's held this trench - the Devonshire's hold it still.

One of the most famous incidents on that bloody first day occurred at the southern end of the Allied line between the villages of Mametz and Montauban.

Captain Wilfred Nevill of the Yorkshire Regiment attached to the 8th Battalion East Surreys purchased two footballs, some would later remember four, on which he wrote Great European Cup Final: East Surreys v Bavarians, and No Referee for the men to pass among themselves as they advanced across no-man’s-land even offering a prize to the first man who could kick it all the way to the German front-line trenches.

This wasn’t mere bravado on the part of Nevill, or an example of that arrogance for which the English are supposedly disposed, but an attempt by him to provide his men with something familiar to ease the tress and distract them from the prospect of imminent death. There were other examples where the order to go over-the-top was signalled by the kicking of a football into no-man’s-land.

But it was Captain Nevill’s coolness under fire that caught the imagination of the British public and for a time at least his name became synonymous with the virtues of courage, duty, and sacrifice that was so evidently on display that July day. The London Illustrated News devoted pages of its publication to the heroism of Nevill and the Surreys while the Daily Mail’s resident poet, Touchstone, commemorated the event in verse:

On through the hail of slaughter

Where gallant comrades fall,

Where blood is poured like water

They drive the trickling ball.

The fear of death before them

Is but an empty name;

True to the land that bore them

The Surreys played the game.

But Wilfred Nevill would not live to enjoy his brief moment in the public eye. Instead, he was last seen apparently sharing a joke with his men and smoking a cigarette - his body was later recovered just yards from the German front-line.

Already astonished at the sight of British Officers leading their men into the attack wearing monocles and carrying what appeared to be walking sticks the Germans reproduced the illustrations of the Surreys not as examples of heroism but of English absurdity and of their callous attitude toward the lives of their men.

But it was this southern sector of the Somme Battlefield that was to see the only tangible Allied success of the day with the British and the French capturing all their first day objectives including the villages of Mametz and Montauban. General Walter Congreve, spying the seemingly little defended open and rolling countryside beyond sensed a breakthrough and urgently wired General Rawlinson with a request for reinforcements to exploit the situation. But the cavalry did not come, instead they were stood down at 3.30 that afternoon, and Congreve received the order to remain where he was.

The one great opportunity of the day had been lost.

The 1 July 1916 had been the bloodiest day in British military history with 57,474 casualties - 19,247 men killed, including 60% of Officers, most in the first hour, and 31,231 wounded many of whom would die over the following few days.

The French who had participated in the only success of the day suffered far fewer casualties - 5,240 with 1,537 men killed.

The Germans had lost 6,226 with 1,912 killed during the preliminary bombardment but some 10,000 of their troops also remained unaccounted for with a great many of these likely to have been blown to smithereens in the explosions caused by the detonation of the mines.

Despite the heavy loss of life and failure to achieve the expected breakthrough Field Marshal Haig and General Rawlinson deemed the attack a success, so much so that the offensive was to continue for a further four months, only ending with the onset of winter.

By its conclusion 95,746 British and Commonwealth soldiers would be dead along with 50,756 of their French Allies for a combined casualty figure of 623,907 killed and wounded.

The Germans also suffered heavy losses, around 450,000 men, mainly as a result of their Commander-in-Chief Erich von Falkenhayn’s demand that no ground be conceded except over a mountain of corpses and their subsequent determination to immediately counterattack wherever possible.

Still, General Haig was to claim a victory if not a decisive one, the Germans had been forced to abandon their assault on Verdun and the British had proven that they could sustain the pressure of a major offensive even if they had advanced barely six miles. His belief in the strategy of attrition and wearing the enemy down gained credence when the Germans abandoned the Somme battlefield in March 1917 and withdrew 30 miles to the more formidable defences of the Hindenburg Line.

All of the gains made at the Somme during four months of bitter struggle, few as they were, would be lost on the first day of the German spring offensive of 1918. But it would be 1 July 1916, that would become etched into the collective British consciousness much as the evacuation from Dunkirk would 24 years later, and not just for its toll in blood and lives but the death that day of the Pals Battalion. The cynical war weariness to which all armies engaged in prolonged struggle invariably succumb replaced the spirit of optimism that had so infused those who had voluntarily embarked upon a joint enterprise of hazardous but heroic endeavour. What had been two years in the making had taken just ten hours to destroy.

Postscript:

Nine Victoria Crosses were awarded for valour beyond the call of duty on 1 July:

Eric Norman Frankland Bell (Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers)

Geoffrey St George Shillington Cather (Royal Irish Fusiliers)

John Lesley Green (RAMC Sherwood Foresters)

Stewart Walter Loudon-Shand (Alexandra, Princess of Wales Own, Yorkshire Regiment)

William Frederick McFadzean (Royal Irish Rifles)

Robert Quigg (Royal Irish Rifles)

Walter Potter Ritchie (Seaforth Highlanders)

George Sanders (West Yorkshire Regiment)

James Youll Turnbull (Highland Light Infantry)

Notable participants of the Somme Battle:

Harold MacMillan (Prime Minister wounded)

Anthony Eden (Prime Minister)

Adolf Hitler (German Chancellor wounded)

Otto Frank (Father of Anne Frank)

JRR Tolkien (Author)

Wyndham Lewis (Author)

H.H Munro - Saki (Author KIA)

Robert Graves (Author)

George Butterworth (Composer KIA)

Arnold Ridley (Actor-wounded)

John Laurie (Actor-Invalided)

Siegfried Sassoon (Poet)

A.A Milne (Author invalided)

Raymond Asquith (Son of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith KIA)

Ernst Junger (Author)

Blaise Cendrars (Author-wounded)

The youngest British soldier to die on the Somme was Albert Barker of the East Yorkshire Regiment, aged 16.

The oldest British soldier to die on the Somme was Lieutenant Henry Webber of the South Lancashire Regiment, aged 68.

The Thiepval Memorial commemorates the names of 72,195 British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in action on the Somme between 1 July and 18 November 1916, whose bodies were never recovered.

Share this post: