The Birkenhead Drill

Posted on 29th March 2022

To take your chance in the thick of a rush, with firing all about,

Is nothing so bad when you cover to ‘and, an’ leave and likin’ to shout;

But to stand an’ be still to the Birken’ead drill is a damn tough bullet to chew,

An’ they done it the Jollies – ‘Er Majesty’s Jollies – soldier an’ sailor too!

Their work was done when it ‘adn’t begun; they was younger nor me an’ you;

Their choice it was plain between drownin’ in ‘eaps an being mopped by the screw,

But they stood ‘an was still to the Birken’ead drill soldier ‘an sailor too!

(Rudyard Kipling, Soldier ‘an Sailor Too)

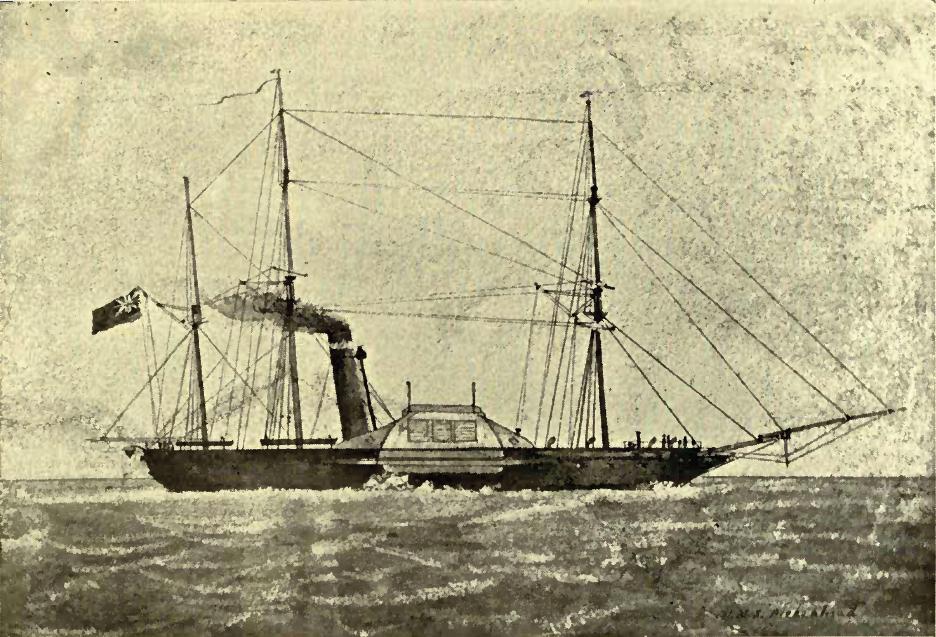

H.M.S Birkenhead built in 1845 was a sea-going paddle steamer with two 564 horsepower steam engines driving two paddle wheels with three sailing masts and a top speed of ten knots. With her iron hull protected by 12 watertight doors separated by strong bulkheads she was made for those long, arduous sea journeys required to service the Empire. As a result, within a few years of her construction she had been commissioned as a troopship.

On 9 January 1852, she set sail from Cork in Ireland bound for Port Elizabeth in South Africa with a complement of 673 souls, 125 crew, 467 Officers and men from ten different regiments, and 81 women and children. Many of the soldiers aboard were barely trained raw recruits desperate to escape grinding poverty or in the case of the Irish the famine that had so recently ravaged their homeland.

The voyage had been long and predictably tedious but incident free with the crew busying themselves as usual, the troops were put through their paces on deck, while the women and children remained mostly in their cabins. On 23 February, they docked at Simon’s Town on the Western Cape where most of the women and children aboard were disembarked. The opportunity was also taken to purchase some horses and load up with coal. It was also a relief for everyone on board to see land again and appreciate the hustle and bustle of a busy port.

At six o’clock on the evening of 25 February, the Birkenhead set sail once more for what should have been the last leg of her journey; but she had fallen behind schedule. It should have taken 37 days to sail from Ireland to South Africa and she was already on Day 49 of her journey, so her Captain Robert Salmond decided to save time by hugging the coastline. To do so wasn’t without menace, it was rugged shore of hidden dangers and unpredictable seas, but Salmond was an experienced mariner, it was a clear night, and the waters were calm. He had also ordered regular soundings to be taken but disaster would strike, nonetheless. The rock it struck at the aptly named Danger Point so clearly visible in stormy weather remained submerged and invisible in calm seas.

At around 2 am on the morning of 26 February, the Birkenhead travelling at around 8 knots rammed into this hidden rock, a collision that occurred with such force that the ships plates were buckled, and its bulkheads torn apart. Many troops were drowned in their bunks as the rock ripped through the hull of the ship. Those who survived were ordered to evacuate with haste and line up on deck.

The senior officer on board Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Seton of the 74th Highland Regiment took command of all army personnel present. He immediately ordered 60 men to return below and assist the crew in manning the pumps. He then stressed to his officers the need to maintain discipline and set an example to their men. In the meantime, Captain Salmond did his best to ascertain the damage – it was serious. He ordered the rockets fired while atop the main mast, a commanding position from where he could be both seen and heard he now directed the crew in their efforts to save the ship. A survivor recalled the scene:

“Almost everyone kept silent, indeed nothing was heard, but the kicking of the horses and the orders of Salmond, all given in a clear firm voice.”

As Seton ordered the frantic horses be driven from the ship Captain Salmond made a fateful decision when to dislodge the ship from the rocks deadly embrace, he ordered its engines put into reverse. Perhaps aware the ship was already doomed it was a last desperate attempt to make a dash for shallower water and possibly beach her but instead it destroyed what remained of the hull.

A little earlier Colonel Seton had informed his troops still lined up on the deck that they were to adopt the Funeral Drill, that if any of them were to be saved it would be the youngest first. Astonishingly no one demurred, there was no panic, as Colonel Seton stood before them his sword unsheathed, his authority was absolute. As Captain Edward Wright of the Argyllshire Regiment recalled at the subsequent Inquiry into the disaster:

“The order and regularity that prevailed from the moment the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I thought could be effected by the best discipline, and it is the more to be wondered at seeing that most of the soldiers were but a short time in the service. Everyone did as he was directed and there was not a murmur or cry amongst them until the ship made her final plunge – all received their orders and carried them out as if they were embarking instead of going to the bottom – I never saw any embarkation conducted with so little noise or confusion.”

There were in fact 8 lifeboats aboard the Birkenhead but having never been used before 6 of them had rusted to their davits and could not be freed. The two cutters, however, could be used and were.

As the Birkenhead began to break up Captain Salmond barked the standard order of the day, “Abandon ship, every man for himself.” He then advised, “All those who can swim jump overboard, and make for the boats.” Colonel Seton who had earlier ordered his men to stand aside to ensure that the 7 women and 13 children still aboard were placed in the boats first before they were launched, aware that if Salmond’s advice was followed the boats would be overwhelmed ordered his men to remain where they were until the boats were a safe distance from the ship: “You will swamp the cutter containing the women and children. I implore you not to do this thing, and order you to stand fast.”

Twenty minutes after striking the rock H.M.S Birkenhead split into two, those still manning the pumps were drowned immediately while the aft section sank in seconds throwing everyone on it into the sea. It was only now that Colonel Seton released his men from their duty suggesting they try and swim for the shore. Lieutenant G.F Girardot of the 43rd Light Infantry in a letter to his father described events:

“I remained on the wreck until she went down, the suction took me down some way, and a man got hold of my leg, but I managed to kick him off and came up and struck out for some pieces of wood that were on the water and started for land, about two miles off. I was in the water about five hours, as the shore was so rocky and the surf ran so high that a great many were lost trying to land. Nearly all those who took to the water without their clothes on were taken by sharks, hundreds of them were all around us, and I saw men taken by them close to me, but as I was dressed (having on a flannel shirt and trousers) they preferred the others. I was not in the least hurt.”

The Great White Sharks were indeed circling and for some it took a terrifying and exhausting twelve hours to reach shore as they clung onto any piece of debris or driftwood they could find. Most of them did not make it even if all the horses except one did.

The following morning the schooner Lioness unaware of the disaster stumbled upon the lifeboats and rescued those aboard. They then made for the area of the tragedy where they found 40 men still clinging to the rigging of the ship.

In total 193 men, women and children survived the loss of the Birkenhead but some 480 did not among them Captain Salmond and Lieutenant-Colonel Seton.

The tragedy that struck the Birkenhead that fateful day would soon become a by-word for courage, discipline, and self-sacrifice even in the most frightening and hopeless of situations. The example set by Seton and his troops would soon become known as the ‘Birkenhead Drill’ immortalised in the poem by Rudyard Kipling quoted earlier.

The story spread far and wide as an example of how men should behave and what should be expected of them. In Prussia Frederick Wilhelm, the future Wilhelm I of a united Germany posted the details of the Birkenhead Disaster in every barrack room in the country with the message that he demanded no less a devotion to duty from his soldiers.

It was also the first time the safety of women and children had been prioritised in such a situation, the marine protocol we now know as “women and children first,” though no order was given using these actual words. They would be heard of course during the more famous Titanic disaster of 1912, if rarely since.

The behaviour of those aboard the Birkenhead is difficult for us to contemplate now let alone understand, it is neither expected nor sought – but we were different people then.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: