The Gordon Riots

Posted on 6th January 2021

In 1778, the Whig politician Sir George Savile moved in Parliament his Bill intended to remove some of the penalties imposed upon Catholics still outstanding from previous legislation. For the most part any reforms were insignificant except for the one that would see Catholics who wished to join the army exempt from the requirement to take an oath that was little short of a renunciation of their faith.

Britain was at the time trying to suppress its rebellious American subjects who along with their allies in France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic were threatening to turn a local conflict into a global war. As a result, the nation’s resources were overstretched, and it was hoped that Sir George’s planned legislation would provide a much-needed boost to recruitment; for this reason alone it was supported by the Ministry of Lord North which saw it passed into law as the Catholic Relief Act.

The passage of the Bill was expected to be controversial, it being so easy to stir up anti- Catholic sentiment in England, but any opposition to it was anticipated to be brief and little more than the usual hot air. After all, the Jacobite menace had long since been laid to rest and Catholicism in general no longer posed a threat in staunchly Protestant England.

Even so, for an Administration as deeply unpopular as Lord North’s, and one so regularly criticised and lampooned in the press for its, mishandling of the American Affair, it presented an element of risk.

Sir George had little care for Lord North’s priorities, in passing the Bill he was seeking to ease the restrictions placed upon Catholics that prevented them from fully participating in the life of the nation; but for many this was a step too far and set a dangerous precedent which if repeated would see Rome once again with its hands on the throat of English liberty, for all know what Catholicism means – a return to absolutism, the Inquisition, superstition, and auto-da-fe on the streets of English towns and cities. It could not and would not be tolerated and the new legislation would see the revival of the Protestant Association under the leadership of its charismatic if somewhat eccentric new President, Lord George Gordon. He had already fought successfully to prevent the Catholic Relief Act becoming law in mostly Calvinist Scotland and now he would seek to do so in England by bringing his campaign south to London and to the doors of Parliament itself

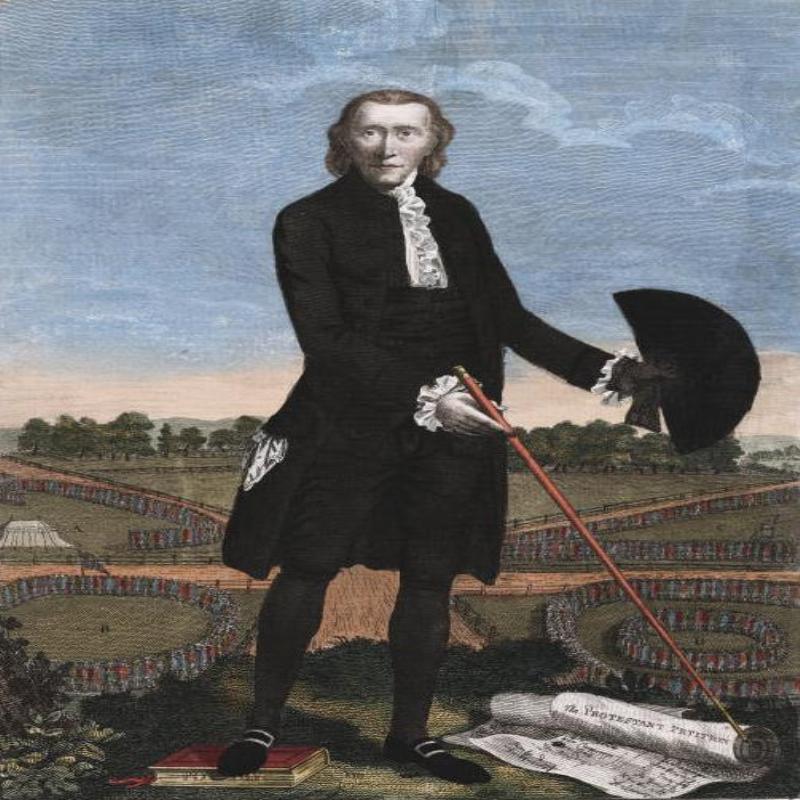

Although he was born in London and educated at Eton, Lord George was a Scots nobleman of the Gordon Clan who as a third son and unlikely to inherit chose the Royal Navy for his career and had already enlisted by the age of 12.

Promoted to the rank of Lieutenant he was never popular with his fellow Officers who thought him not only a little odd but too close to the men to be fully trusted. When in 1773, the First Lord of the Admiralty the Earl of Sandwich refused him command of his own ship he resigned his Commission having received several endorsements that suggested a political career beckoned – he was right.

In the General Election of 1774, he was returned as the Member of Parliament for the Constituency of Ludgershall, one of the notorious Pocket Boroughs that were available either for purchase or in the gift of the local landowner or peer.

To suggest that Lord George was a maverick would be to understate it, temperamental and outspoken he was highly critical of the Prime Minister Lord North but no less so of his great rival the Radical leader Charles James Fox. Needless to say, it made him beloved of no one a situation little improved by his vocal support for the American Colonists in their struggle against the British Crown.

But by now he had found a cause closer to home.

Popular with the people, whom he was never shy of addressing, as much for his colourful use of the vernacular and unusual demeanour as his views the Authorities always wary of the next charlatan or demagogue attempted to placate Sir George and he was to have several private meetings with the King, that was until George III could bear it no longer and (with some irony given future events) declared him completely mad and banned him from the Royal Court.

London by the 1780’s was already a teeming metropolis, the commercial and financial centre of the world, a place of grandeur and display where a man could make his mark and his fortune; but with over a million people increasing daily its dark alleys and narrow streets were overcrowded, filthy, and rife with disease. Drunkenness and licentious behaviour were commonplace and with a thriving criminal underworld violence and disorder only ever simmered beneath the surface.

With little law and order to speak of (there were of course Magistrates, Watchmen, and the recently instituted Bow Street Runners to make arrests but no police presence on the streets) London was a place of riot waiting to happen, never a case of if but when – it was a city on a knife edge.

The dread of the mob in London was acutely felt and not dissimilar to that expressed by the elite of Rome a thousand years before. There was a genuine fear that a demagogic figure would rouse the people to such a pitch of fury and hatred, that the violence and destruction would be so intense as to be uncontrollable and would turn its rage not upon property but the Institutions of State. Had that figure arrived in the person of Lord George Gordon? It seemed so to some, but not to others.

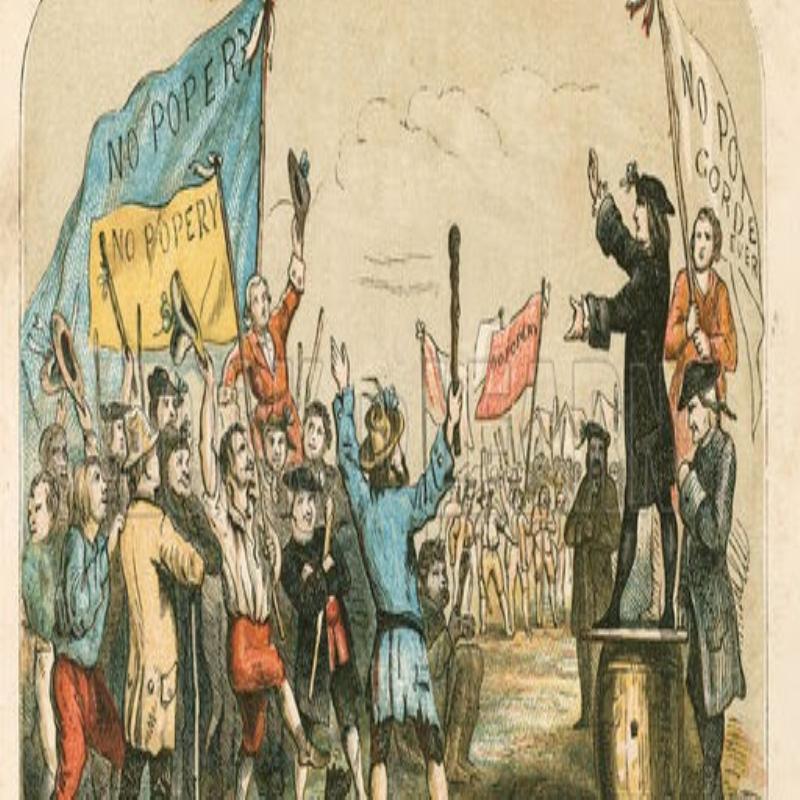

The Protestant Association had been propagandising for some months with the sermons of popular preachers such as Rowland Hill and Erasmus Middleton well attended and influential. The ground had been well laid, and Lord George now exhorted the people to follow him on a march the centre of power and he demanded they come in their tens of thousands, if not then he wouldn’t march at all and the Jesuits can return with their rosary beads and the rack.

Having assembled at St George’s Fields in Southwark on 2 June 1780, with Lord George at their head some 50,000 people, described as ‘the better kind of tradesperson’ set off in procession for the Houses of Parliament in Westminster intending to lend their support to Lord George as he delivered in person their petition demanding the immediate repeal of the Catholic Relief Act and an assurance from the Government that there would be no further moves towards Catholic Emancipation.

Many of the marchers wore the blue cockade of the Protestant Association in their hats while others carried flags and banners emblazoned with the words ‘No Popery’ and such like. The mood was boisterous rather than violent, but this would change as tens of thousands of ordinary Londoners swelled its ranks and soon it would not be flags waved but effigies being burned that dominated the London skyline. By the time the marchers neared their destination the column stretched back four miles.

A local storekeeper Ignatius Sancho left us a description:

“At least 100,000 were miserable, ragged rabble from 12 to 60 years of age, besides half as many women and children all parading in the streets, the park, on the bridge, ready for any and every mischief.”

The Parliament Building was largely undefended other than for a few elderly doormen and some of the more aggressive younger Members and so had little choice but to allow Lord George to deliver his petition:

“Lord George came into the House of Commons with an unembarrassed countenance and a blue cockade in his hat, but finding it gave offence he took it and put it in his pocket, but not before a Captain Herbert, one of the Members threatened to pull it out, while Colonel Murray, another Member warned him that should the mob break into the House hr would be the first victim.”

But the crowd increasingly threatening and still swarming around the building did not disperse, neither did Lord George request they should. It was not within his power to order people to obey him, he would later say, that authority lay elsewhere.

It was in fact the responsibility of Brackley Kennet, the Lord Mayor of London, to read the crowd the Riot Act which declared any assembly of 12 or more people to be unlawful and when called upon must disperse or face punishment. That he did not do so was remiss of him and his negligible grasp of the situation barely improved thereafter.

No doubt fuelled by alcohol (several Gin Houses had already been broken into) the mob now tried to force its way into the Parliament Building and a few MP’s either trying to enter or exit were dragged from their carriages and roughed up.

The Times Newspaper reported on events:

“They attempted in like manner to force their way into the House of Peers but by the good management of Sir Francis Molyneux and the proper exertion of the doorkeepers the passages from the street door and around the House were kept open.

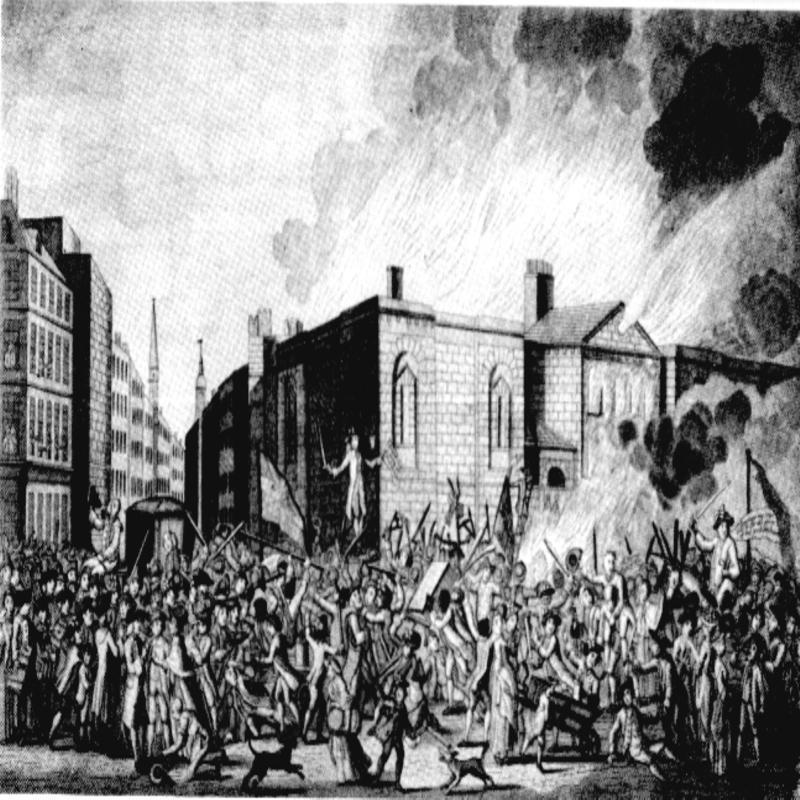

About ten o’clock the mob made a parade in different directions from the Palace Yard where part of them went to the Roman Chapel in Lincolns-in-Field where they began to break down the doors, and then pulled down the rails, seats, pews, communion table brought them into the street, laid them against the doors and set fire to them. About eleven o’clock the Guards came, and much rioting ensued. They took several of the ringleader’s prisoner but with the assistance of the mob they made good their escape.”

The rioting spread rapidly and though much of the violence was random the homes of the rich and powerful soon became targets with those of leading politicians such as the former and future Prime Minister the Marquis of Rockingham, the Duke of Devonshire, the hated Chief Magistrate, the Earl of Mansfield, and indeed Sir George Savile himself, being stoned and having their windows smashed. Some were even burned.

And the violence would not relent over the coming days, if anything it became even more intense with anything that could be identified as Catholic likely to be attacked with more than 100 Chapels and Churches trashed, looted, and torched. Even foreign Embassies such as the Sardinian and Bavarian were besieged as their residents cowered behind their walls in fear of their lives.

The absence of any visible authority on the streets (a small number of arrests were made by the thinly stretched and over-burdened Bow Street Runners but most soon eluded their captors) allowed the mob to act with impunity and 36 major conflagrations were reported to have broken out in London many at the same time with little attempt to douse the flames other than by locals whose own homes were threatened by them.

Some of the worst rioting and incidents of violence occurred in the Moorfields district, one of the few areas of open land in London and home to a great many Catholic Irish immigrants and a place notorious for its brothels, taverns, and as a hiding place for highwaymen and those eluding justice.

Aware they would serve as a magnet for the rioters leading Catholics approached the Lord Mayor pleading for protection, but none was forthcoming and as the mob descended many fled leaving their homes to be broken into and ransacked - those who remained were likely to be beaten or subjected to public humiliation.

TThe mob rampaged through the streets of London virtually unchecked for five days and it wasn’t until 7 June when they converged upon and threatened to break into the Bank of England that following consultations with the King, Lord North at last ordered troops onto the streets to restore order. They could only do so by opening fire on the crowds and around 450 people were killed and 700 wounded.

The Militia sent to defend the Bank of England was commanded by John Wilkes, the famous Radical MP who had himself ten years earlier been the darling of the mob, now he too ordered his troops to open fire. His reputation never recovered.

The crowds dispersed over the next few days leaving carnage behind them – shops looted, churches burned, homes ransacked, streets in ruins. Some returned home nursing sore heads, others with broken bones and gunshot wounds. Others disappeared back into the London fog laden with booty, some of course never returned home at all.

In the immediate aftermath the Government dismissed the rioters as being the refuse of society and not true Englishmen, they were foreigners, gypsies, vagabonds, beggars, and thieves. Hundreds were arrested and 25 executed, people such as the Jew Samuel Solomon from Whitechapel and the black washerwoman Charlotte Gardiner both hanged for demolishing a house; the street thug William Taplin who extorted money with menaces in the name of the Protestant Association he said, but in truth to line his own pockets; and the ex-soldier William MacDonald who had lost his arm in service to the Crown but was now hanged for damaging property.

But many of those subject to fines, deportation, terms of imprisonment, and worse were respectable in their daily lives and as such less worthy of reporting.

Lord George Gordon, who had not participated in the riots even if some believed he had instigated them, was also arrested, and arraigned at the Old Bailey charged with treason.

Incarcerated in the Tower of London he was shown all the respect due his rank, his cell was furnished to his liking, he ate regularly and well, and he was permitted visitors among them the leading Methodist preacher John Wesley. His connections also ensured that he had the best possible Defence Counsel, a close family friend Lord Erskine who successfully argued during the trial that in delivering a petition to Parliament for the consideration of its Members he could hardly be accused of committing a treasonable act nor could he be held responsible for people whose behaviour he had had at no time incited or encouraged – he was acquitted of all charges.

The man who would be blamed was Brackley Kennet, the Lord Mayor of London who had failed to respond sufficiently to events and was fined £1,000 for criminal negligence.

The riots had to all intents-and-purposes ended Lord George’s political career and over the next few years his behaviour became increasingly erratic. In 1786 he was excommunicated by the Archbishop of Canterbury for his refusal to appear as a witness before an Ecclesiastical Court and a year later fled abroad to avoid arrest for alleged defamation. He was to return but “apprehended in Birmingham in the garb of a Jew with a long beard and having undergone circumcision he had embraced the religion of the unbelievers.”

Lord George was to be sentenced to five years imprisonment, not for his conversion but the charge of defamation outstanding against him which he strenuously denied.

Despite his erratic, some would later say insane behaviour, it still came as a surprise to discover that the former President of the Protestant Association and the man who had been sparked the most serious anti-Catholic riots ever seen in England had converted to Judaism, old friends and colleagues were genuinely shocked:

"Unknown to every class of man but those of the Jewish religion, among whom he has passed his time in the greatest cordiality and friendship . . . he also appears with a beard of extraordinary length, and the usual raiment of a Jew.”

He had not done so on a whim (he was never less than earnest) and in gaol he lived as an Orthodox Jew does following the Dietary Laws as best, he could, often without success.

Many of those disappointed that they had lost their champion claimed that he had been bewitched by a Jewess he lived with while abroad, but for all his faults he was never less than sincere.

In January 1793, he was considered for release, but the Court would not accept the testimony of the two Jews he had chosen to bear witness on his behalf. His family then offered to pay his bail, but Lord George refused their help insisting that to pay for his release would be to admit his guilt, and this he wouldn’t do.

As a result, he remained in prison where soon after he contracted typhoid fever.

On 1 November 1793 aged 42, Lord George Gordon still professing the faith of his conversion died.

“Such was the end of a man, once, perhaps, the most popular idol of the mob, and, for some days, the terror of all London.”

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: