The Innocence of Pontius Pilate?

Posted on 21st July 2021

The story is told how many years ago a young Russian Jew was paid a rouble a month by the local Mayor to stand on the outskirts of his town so that should the Messiah return there would always be someone there to greet him. When a friend of the young man complained that the pay was too low and that he should ask for more, he replied: “I know the pay is poor but at least the work is permanent.”

But whereas the Coming of the Messiah remains a matter of dispute among Jews for one breakaway sect it long ago ceased to be the subject of intellectual debate for the Christians declared Jesus, the carpenter’s son from Nazareth who lived and preached in the land of Israel, to be their Messiah - the Son of God subject to a Virgin Birth who died upon the Cross for the remission of their sins.

But who killed Jesus, who was responsible for the death of the Messiah? Was it Pontius Pilate, the Roman Governor of Judea? Caiaphas, the High Priest of the Jewish Temple? Or was it the Jewish people who had themselves demanded it?

It is written that Pontius Pilate only reluctantly ordered the crucifixion of Jesus, and upon this the Gospels, which otherwise vary in their accounts, agree. But did he, would he, could he have been so ambivalent and indecisive? If so, then he was a strange choice as Governor of the most turbulent and fractious of all the Roman provinces? If so, then it would appear to have been out of character.

According to Philo of Alexandria, Pilate was a vindictive man of violent temper who was wilful, inflexible, and relentless in pursuit of his aims. He likewise criticised “his corruption and acts of insolence, his rapine and habit of insulting people, his cruelty, and his murder of people untried and un-condemned, and his never ending, gratuitous and most grievous inhumanity.”

Indeed, it was his cruel and arbitrary behaviour that the Jewish historian Josephus tells us was the reason behind his recall to Rome. He does not then, seem a character who would demur at the execution of a heretic preacher.

He had been born a Roman citizen but was not of Roman ancestry, rather he was a Samnite, a member of a hardy tribe from the mountain country of south-central Italy that had fought long and hard to resist Roman rule. By the time he reached adulthood the Samnites had only been fully assimilated into Roman society for a hundred years or less and they were still not entirely trusted. They were considered outsiders still and sensing the need to prove and reaffirm his loyalty constantly Pilate would have had to try harder than most to succeed.

Even though he was of noble blood, a member of the Pontii clan, as a Samnite he could not rise above the rank of Equestrian, the lowest strata of Roman nobility making political advancement based on status alone difficult and unlikely, so he instead chose a more traditional route for an ambitious young man of limited opportunities, he enlisted in the army.

In the Legions Pilate would have learned to be ruthless and hard but as an outsider would he not also have felt an empathy with, perhaps even sympathy for, others similarly marginalised. Who knows, but he was good soldier and rose rapidly through the ranks displaying a flair for leadership and administration as he did so.

In AD 26 his hard work was rewarded when he was appointed Prefect, or Governor, of Judea - his remit a simple one, to maintain order and collect taxes.

Caiaphas as High Priest of the Jewish Temple in Rome presided over the Sahnredin, the Supreme Council that administered to Jewish affairs religious and otherwise. He could be high handed in the delivery of his duties and lived in conspicuous luxury courtesy of his willingness to co-operate with the Roman occupiers. It was not something that had gone unnoticed by those who sought a change to the status quo but then his task was to ensure that the Jewish people remained compliant and that no serious threat emerged to Roman rule.

Religious preachers were not uncommon in Judea and Roman policy (such as it was) towards them was one of indifference as long as they did not advocate for rebellion and posed no threat. One such man was John the Baptist who had been practising his ministry along the banks of the River Jordan for a number of years. But Roman toleration of such activities was not necessarily mirrored by the Sahnredin who saw all such preachers as a direct challenge to their authority and were particularly concerned by all the constant chatter of a coming Messiah.

A preacher, Joshua Bar-Joseph, known as Jesus, had been gathering disciples for only a short time but his popularity had been noted and his growing reputation as a healer and miracle worker saw his name spoken of in the same breath as that of the Messiah.

Caiaphas felt threatened by this Jesus whom he not only thought was preaching against him but showing great disrespect by his repeated attacks upon the Temple, the very hub of Jewish life and commerce, where it barely needed saying, the blasphemy committed was both stark and absolute.

Before entering the Temple, a Jew had to be ritually cleansed in a mikveh, or bathtub, for which the priests charged a fee and once inside the Temple there were business transactions to be seen aplenty - it had, or so it seemed, ceased to be a place of worship and had instead become a centre of corruption, graft, and greed. Jesus was furious and storming into the Temple, overturned the tables, and drove out the moneychangers:

“My house shall be called the house of prayer, but ye have made it into a den of thieves,” he said.

His behaviour was thought scandalous; to verbally attack the Jewish Religious Establishment was one thing but to assail their holiest shrine and threaten their wealth was another.

Caiaphas was unequivocal in his condemnation. Such behaviour could not be tolerated even if this meant the preachers death. Others among the priesthood were not so sure. His criticism was not without foundation, after all. He had condemned the money changers for defiling the sanctity of the Temple which was self-evidently true. But Caiaphas was adamant - by physically attacking the Temple he had committed a crime against God?

Even if his blasphemy could be proved to commit an offence under Jewish law was not to commit one under Roman law and Caiaphas who did not want the responsibility for condemning Jesus wanted Pilate to do it.

Pilate may have had the reputation of a man who trampled upon the religious sensibilities of those he governed but he was no fool. As far as he was concerned Jesus had committed no crime under Roman law. His priority was to maintain order and collect taxes not launder the Jews dirty linen for them. But the Sahnredin having already condemned Jesus under Mosaic Law and taking their instructions from Caiaphas now accused him of openly opposing the payment of taxes to Caesar and to Rome even though he had already declared “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” Words that are to be plainly understood but tax resistance could not be tolerated and was a capital offence. Pilate knew this and so did Caiaphas.

Four days after raising Lazarus from the dead in the village of Bethany, Jesus descended from the Mount of Olives to ride through Jerusalem on a donkey. It was Passover and the city was teeming with people who in anticipation of his arrival had strewn flowers and palms along his path.

Aware that tensions were often high during Passover, Pilate who resided in Caesaria and rarely visited Jerusalem was in the city for the festivities, his presence a reminder, should anyone be inclined towards dissent, who still governed in Judea.

A short time after events in the Temple, Judas Iscariot, one of the disciples and a close associate of Jesus approached the Jewish Authorities and agreed to betray him for the payment of 30 pieces of silver. Later at what became known as the Last Supper, Jesus told his followers that despite their assertions to the contrary one of their number would betray him. The following day he was arrested as he walked in the Garden of Gethsemane after Judas had identified him with a kiss on the cheek.

As the priests and the guards who accompanied them moved in to seize Jesus a scuffle broke out, weapons were drawn, and blows struck. To prevent further violence Jesus intervened telling his disciples: “Return your swords to their place, they who take up the sword will die by the sword.”

Judas, distraught at what he had done would later hang himself.

Taken before the Sahnredin Jesus angered Caiaphas by refusing to be cowed in his presence and infuriated him further by remaining silent under questioning spurring the High Priest to cry out in frustration: Will thou answer me nothing! At last, to the question: are you Christ the son of the Blessed? He replied: I am, causing an increasingly agitated Caiaphas to tear at his cloak and demand “Are you then the Son of God?” Jesus, who had in contrast to his me nothing interlocutor remained calm, replied cryptically, “You say that I am.”

It was enough for Caiaphas, there was no need for witnesses the accused had declared himself King of the Jews and admitted his guilt. He ordered that he be taken to Pilate.

Pilate couldn’t care less that some itinerant preacher had declared himself King of the Jews - it wasn’t his affair. He sent him to Herod Antipas in Galilee under whose jurisdiction he fell.

Herod, who drunk and amorous had only recently succumbed to the wiles of his stepdaughter Salome and her Dance of the Seven Veils presenting her with the head of John the Baptist as a reward was disinclined to offend God any further. It was his want to mock, humiliate and belittle Jesus demanding that he perform miracles for his entertainment, but he would not take responsibility for his execution - he returned him to Pilate.

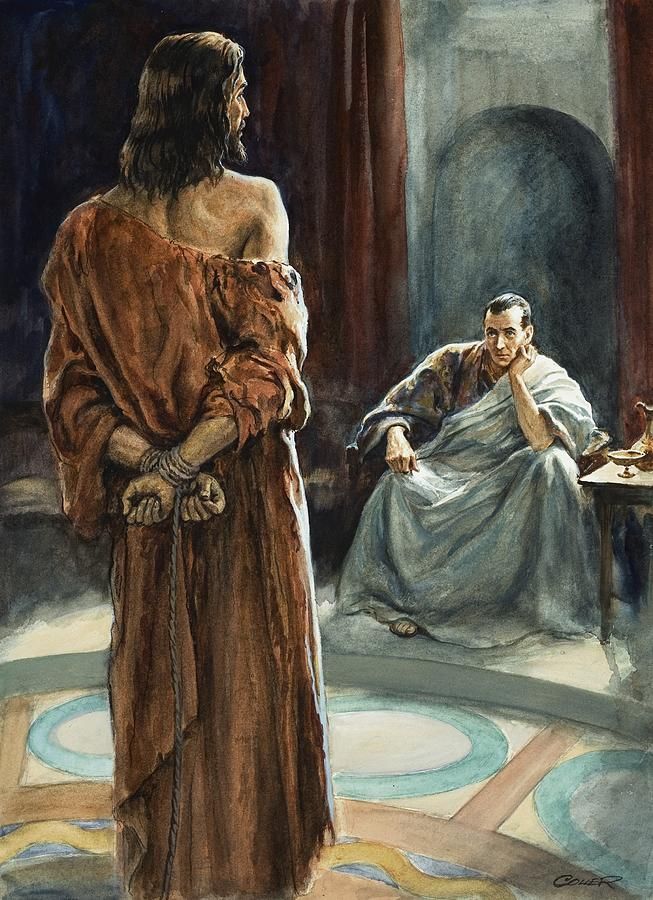

It came as no surprise to Pilate that the idiot Herod had returned Jesus to his care but it was unwelcome nonetheless especially as Caiaphas and the Sahnredin weren’t about to let the matter lie. They continued to harangue the Governor until at last he determined to meet the preacher, the holy man, who was causing him such grief.

Their meeting would be brief but deeply profound in its simplicity. There would be little to add, all that could be said would be said.

Pilate asked the preacher: “Do you consider yourself to be the King of the Jews?”

Jesus replied: “If you say it is so, but my Kingdom is not of this world. I came into this world to bear witness to the truth, and all who are on the side of truth listen to my voice.”

Pilate paused for a moment before replying: “What is truth?

It is the question of eternal memory the resolution of which lies in the redemption of man but even as the answer stood erect before him Pilate could see nothing. But he had been disturbed by the exchange, moved even. His verdict: I find no fault in this man. Caiaphas disagreed, and he was quick to remind Pilate that to declare oneself King of the Jews was to declare oneself against Caesar - how would the Emperor in Rome react to such an assertion going unpunished? Pilate could only say once again, I find no guilt in this man.

His wife Claudia Procula agreed, she whispered in his ear of a dream she’d had. It was a warning she told him: “Have nothing to do with this righteous, innocent man for I have suffered many things this day because of a dream I had.” Caiaphas whispered in his other ear: “If you release this man, you are no friend of Caesar’s.”

Jesus would be condemned. It could not be otherwise but what should be his punishment?

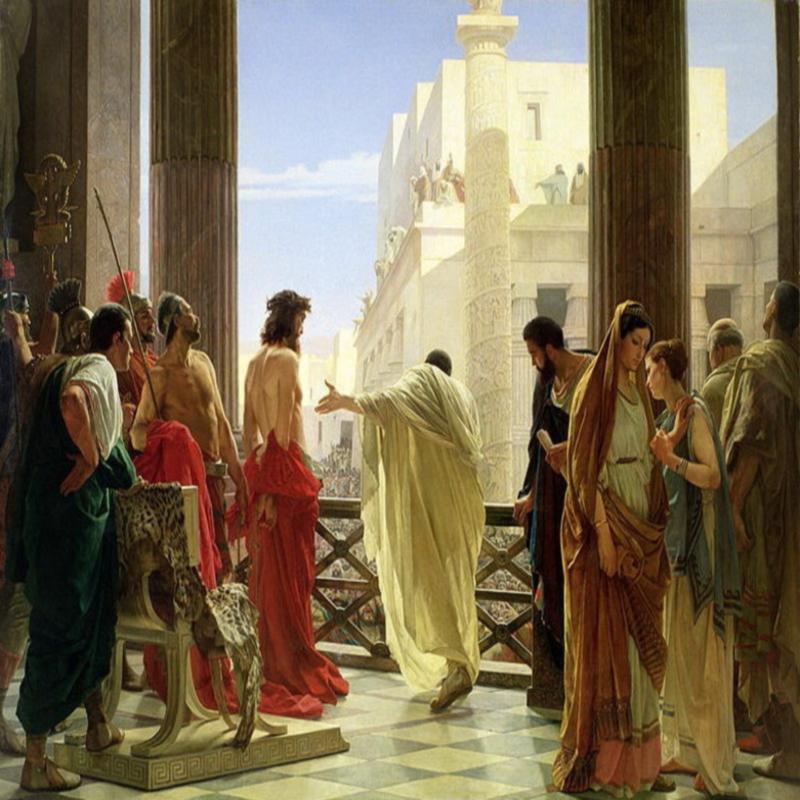

It was the custom during Passover for the Prefect to release a condemned man according to public acclamation. Pilate put the question to the crowd – should the preacher be set free?

They responded, “Let his blood be upon our heads, and the heads of our children,” and chose instead a common thief named Barrabbas. But why, asked Pilate, “what evil has he done?”

They chanted back “crucify him, crucify him!”

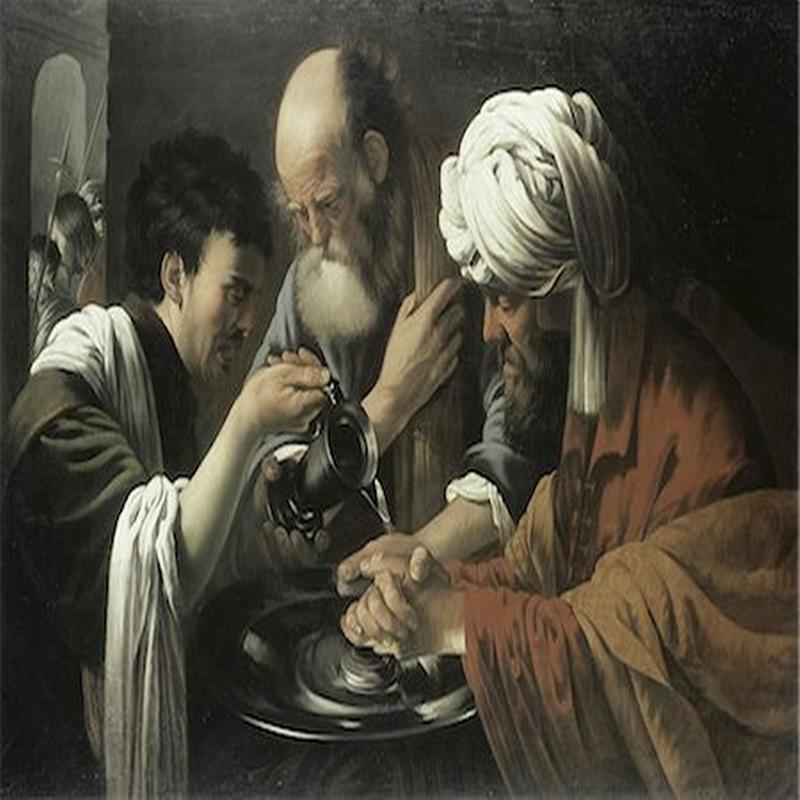

Pilate yields to their demand but then washes his hands in full view of the crowd before saying to those accompanying him: “I am innocent of this man’s blood, see you to it.”

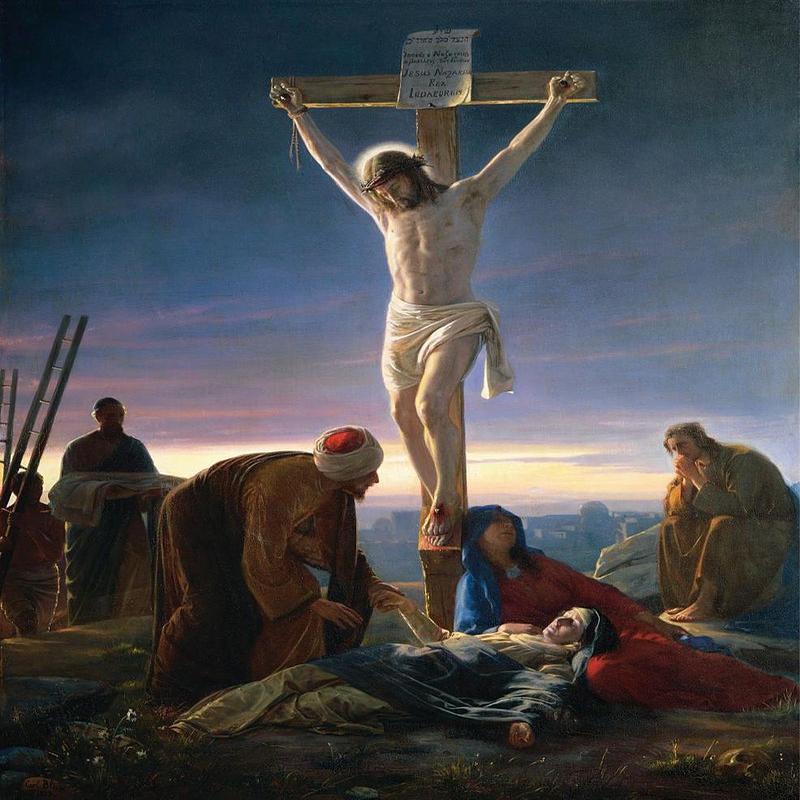

Made to wear a crown of thorns in mockery of his claim to Kingship, Jesus, relentlessly scourged and beaten as he did so was forced to carry the Cross to which he would be nailed upon his back along the Via Dolorosa to his place of crucifixion on the hill of Calvary overlooking the city.

The many women who lined the route hearing the jeers and seeing the blood and torn flesh wept at the torture he was forced to endure but he told them not to weep for him but for themselves and their children.

Nailed to the Cross with his arms outstretched Jesus did not cry out or beg for mercy much to the irritation of Caiaphas and many of those looking on, no doubt. Meanwhile, Pilate had pinned above his head a sign which read: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. When Caiaphas complained that he was not King of the Jews only claimed to be and that the sign should be taken down Pilate refused saying: “I have written what I have written.”

Jesus would die on the Cross for the remission of our sins, be resurrected and ascend to heaven. Pilate too would die, but in Rome, made to account for his actions, condemned, and ordered to take his own life by the man he served, the Emperor Caligula.

Few ponder much upon the fate of Pontius Pilate, and fewer still that of Caiaphas, but the death of Jesus remains forever etched in the heart and soul of man whether one wishes so or not, that is the truth of eternal memory; but that it was meant to be surely negates the requirement for blame and all then are guilty and innocent in equal measure? Maybe, maybe not, it falls to man to find the imponderable intolerable.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: