The King's Nemesis

Posted on 22nd September 2021

The future King Charles I was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, on 19 November 1600. As the second son of King James VI, he was never expected to rule the heir to the throne being his much-admired elder brother Henry.

Henry was everything that his brother Charles was not, he was tall, athletic, boisterous and enjoyed hunting and sports passions that he shared with his father. He was also a committed Protestant and somewhat of a prig even having a swear box installed in his Chambers.

The combination of athleticism and pious religiosity was to make Henry the most popular young Prince England had seen for many years. His popularity with the people was not shared by his father with whom he argued often and loudly. Once on a hunting trip together in Royston they squabbled, and Henry took hold of his cane as if making to strike his father but was prevented from doing so. James was no doubt jealous of his son given that the English had long ago fallen out of love was him.

In the winter of 1612, the eighteen-year-old Henry fell ill with typhoid fever and took to his bed; Charles, who was in awe of his brother despite the bullying that was a feature of their relationship was a constant presence at his brother’s bedside.

As Henry’s condition worsened Charles brought him a small bronze horse which he placed in his brother’s hands believing it would comfort him. It was a touching moment and one of the last times Charles would see him for on 6 November 1612, Henry died to great national mourning. The lamentations were long and many:

“His body was so fair and strong that a soule might have been pleased to live an age in it, vertue and valor, beauty and chastity, armies and arts met and kist him.”

The heir to the throne would now be the shy, diffident, little regarded twelve-year-old Charles who himself fell ill soon after his brother’s afflicted by nerves. He was however to be the Chief Mourner at his funeral after James declined to attend saying that he hated death and all that it entailed.

Charles had been a sickly child, so sick in fact that he wasn’t expected to survive infancy. So, when his father had travelled south for his coronation as King of England on 25 July 1603, he had been left in Scotland, it being felt that the journey would be too much for him to endure.

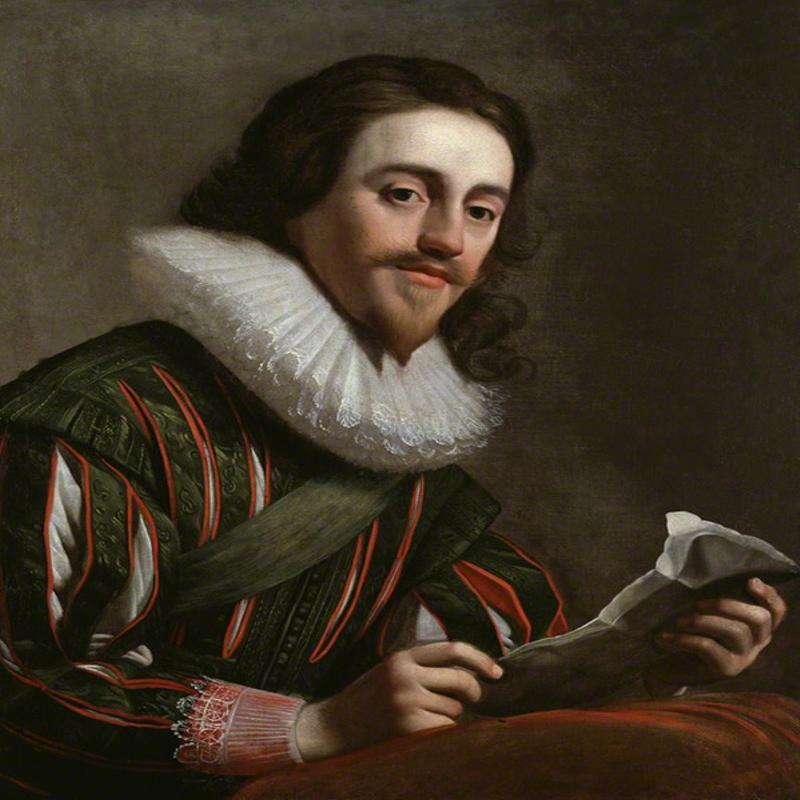

His pronounced stammer made talking a trial for him and he had difficulty walking and so his carer Lady Carey, had a special brace made to support his legs. He was small, never growing to more than five feet four inches, thin, long faced and with a pallid complexion that some were later to describe as like marble.

Charles was to become physically stronger over time though he was never to fully conquer his stammer and trained in the military arts he became an adept swordsman, marksman, and a fine horseman. He was also a well-read, scholarly and sober young man who took his responsibilities very seriously and was often appalled at the behaviour of his father and the raucous and licentious Court he presided over.

James I was a spendthrift whose constant need for money drove those who were charged with finding it for him to distraction. He held frequent lavish parties, danced late into the night, and drank heavily. Yet for all the crude humour, coarse language and falling-down drunk, James was possibly the most intelligent man ever to sit upon the throne of England. He had authored various books and pamphlets including one on Demonology and another on Kingship and had authorised the compiling of the Bible named after him. He was also shrewd and politically astute even if his personal behaviour left something to be desired. It was to earn him the backhanded accolade of “the wisest fool in Christendom.”

Despite a happy marriage to his Queen, Anne of Denmark, that saw the issue of seven children it was evident to everyone at Court that his sexual preferences lay with the many young men that were constantly in his presence and with one young man in particular, George Villiers, twenty-five years his junior whom he would later elevate to become the Duke of Buckingham.

James at this time was described as being, “of middle stature, more corpulent through his clothes than his body, yet fat enough, his clothes being made large and ever easy, the doublets quilted for stiletto proof, his breeches in pleats and full stuffed . . . his eye was large and ever rolling after any stranger that came into his presence, as so much as many for shame had left the room, as being out of countenance . . . his legs were very weak, and that weakness made him ever leaning on other men’s shoulders; his walk was ever circular, his fingers ever without fiddling with his codpiece.”

His affair with Buckingham was a passionate and public one. He would refer to him as “my sweetheart” and his letters to him give us an insight into their relationship: “And so God Bless you my sweet child and wife and grant that ye may ever be a comfort to your dear father and husband”, while Buckingham would frequently sign off his letters to the King with the words “Your Majesty’s most humble slave and dog.”

Their relationship was the scandal of the Court and Buckingham believed that just as he had wheedled his way into the affections of the old King he could now do so with the young Prince Charles.

To the naive but earnest Charles, Buckingham was a learned man of the world, and it was Buckingham who convinced him to journey to Spain and woo the Spanish Infanta wearing a false moustache and using the alias Smith. A more astute man might have demurred at such shenanigans, but Charles was not that man and was to be as much in awe of Buckingham as his father had been.

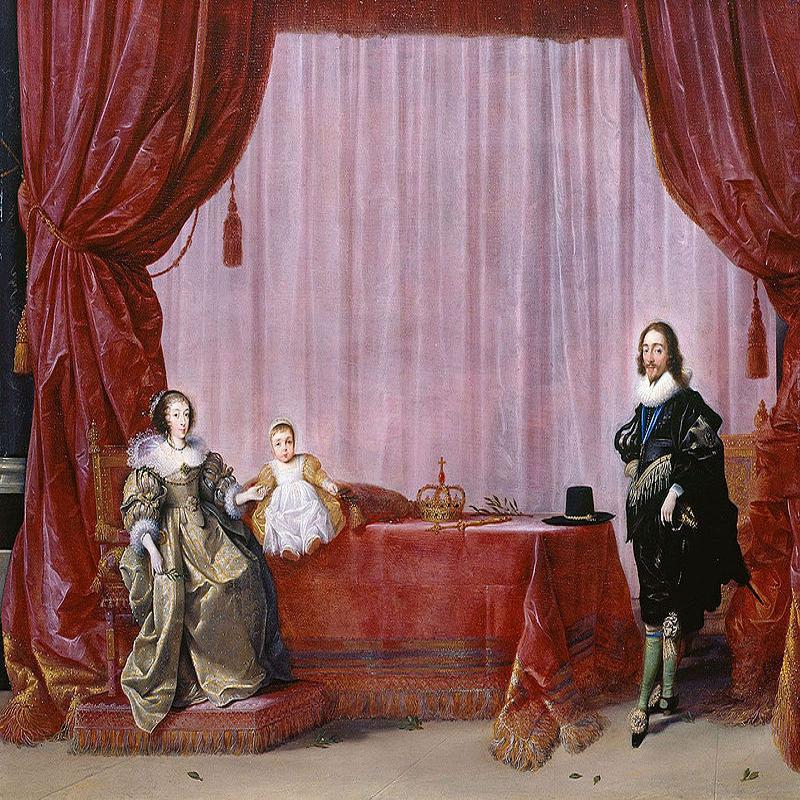

On 13 June 1625, Charles controversially married the sixteen-year-old French Catholic Henrietta Maria. The marriage had been brokered by Buckingham and was greeted with a mixture of anger and dread at Court. Their fears were confirmed when the following year she refused to accompany her husband to his Coronation on the grounds that she would not attend a Protestant ceremony.

Meanwhile, her daily procession through the streets of London to attend Catholic Mass were greeted by a mixture of cheers, jeers, and the discordant sermons of a multitude of hostile preachers.

The people were not in love with their Catholic Queen neither it seems was the King for they were less than the perfect match. Her personality was at odds with that of her husband. It was not an auspicious start to their marriage.

By no means beautiful with her sallow skin and crooked teeth Henrietta Maria more than made up for a plain demeanour with a lively, vivacious and good-natured manner. Few people who met her appear to have disliked her, few people except for her husband that is who found her loud, outspoken and demanding, so much so in that he could not bear to be in her company. He much preferred to be in the presence of his favourite Buckingham whom Henrietta Maria despised as a leech who wielded undue influence over her husband. It was a view widely held but one that she at least was willing to express to the King’s face and in the presence of others including Buckingham himself.

The constant bickering and Henrietta Maria’s refusal to remain silent on the issue of Buckingham saw her relationship with Charles decline to the point where she remained with her French retinue and refused to attend Court. In the end Charles ordered them all out of the country except for two ladies-in-waiting and her Chaplain. In response she threatened to go as well.

The Coronation of Charles I took place at Westminster Abbey on 2 February 1626. It was a solemn affair and not one that the painfully shy Charles particularly enjoyed. Indeed, he was not to repeat the performance for the benefit of his Scottish subjects for another seven years which many north of the border were to consider a deliberate snub.

The reign of James I had been appreciated as a period of unprecedented peace and low taxes even if the character of the man was not. It was hoped that the new King’s reign would usher in a period of greater decorum and here at least he did not disappoint as the Royal Court was restored to a place of propriety, courtesy, and proper conduct.

The new King had a fractious relationship with his Parliament from the outset. His father had summoned Parliament reluctantly and infrequently and even then, they invariably had to endure a lecture from him. Charles’ attitude towards Parliament was not dissimilar in that he would consult them in their capacity as representatives of the people but only when he chose to and on matters, he deemed fit. Those Members of Parliament who held the purse strings did not see it this way, and unlike his father who for all his truculence had known when to compromise, Charles would have to be forced to make concessions.

No one did more to poison the relationship between the King and his Parliament than the Duke of Buckingham. Charles decided, like many before him and many since, that the best and most effective way to stamp his authority on his reign would be a foreign war. He was eager to support of the Protestant cause in the on-going Thirty Years War that was ravaging the European Continent. He required Parliament however to grant him the money to do so and they were reluctant to release any funds as long as Buckingham was to command the expedition. In the end they did but with provisos. It was to be for far less than the King had requested and was to be renewable every year.

On 1 November 1625, a naval expedition set sail to attack the Spanish port of Cadiz that place of former triumph and blessed memory. But not this time as dozens of ships were lost and 8,000 men killed for no gain. Buckingham had also squandered £140,000, more than two-thirds of the money the King had been granted.

The fiasco at Cadiz came as little surprise to anyone and Parliament now demanded the removal of the incompetent upstart Buckingham. When Charles failed to comply in April 1626, they began impeachment proceedings against him.

On 12 June, they wrote to the King: “We protest before your Majesty and the whole world that until this great person be removed from intermeddling with the great affairs of State, we are out of hope of any good success, and we do fear that any money we shall and can give, will, through his misemployment be turned rather to the hurt and prejudice of your Kingdom.”

Charles was furious that Parliament was impertinent enough to address him regarding who they thought fit and proper to be his advisors. He would not under any circumstances permit Buckingham’s impeachment, and so to thwart any attempt to do so he dissolved Parliament.

As if to confirm Parliament in their view a few months later Buckingham squandered what remained of their money in a ridiculously botched assault on the French port of La Rochelle. It seemed as if the problem of Buckingham would never go away until on 23 August 1628, he was stabbed to death in Portsmouth by John Felton, a disgruntled soldier, to whom unsurprisingly he owed money. His murder was greeted with a huge sigh of relief by everyone except the King.

Charles had shown himself to be unwilling or incapable of working with his Parliament without whose consent and support he could not find the money to administer his Kingdom, so other means had to be found. With the assistance of his Attorney-General William Noy an old rarely called upon form of taxation was discovered still upon the statute book – Ship Money. This was an emergency tax raised at times of impending war from the ports and coastal areas to provide men, ships, and supplies for defence. Such was the level of resistance to it that when it was first mooted in 1628 the King thought it best to withdraw the writ, but it had not been forgotten and the writ was reissued in 1634.

Yet again it was met with resistance, some towns claimed exemption under their charters whilst certain individuals complained publicly and paid up only reluctantly. Even so the tax was renewed year after year and extended across the entire country.

In 1637, the respected Buckinghamshire gentleman and former Member of Parliament John Hampden refused to open his coffers to the King’s sticky fingered excise men. He claimed that inland counties were not responsible for coastal defence and so therefore the tax was iniquitous. He was also aware that this was how the King intended to extend his personal rule indefinitely without having recourse to his Parliament.

For his refusal to pay, Hampden was forced to appear before the Star Chamber. Even though there were no real constitutional grounds upon which to oppose the collection of Ship Money, so unpopular was its imposition and the widespread public support for Hampden that though the Court found in favour of the King it was only by a vote of 7 to 5. It was a clear indication of the growing opposition to his personal rule.

This Charles could neither comprehend nor understand; as far as he was concerned, he had been a goodly and just King and he ploughed on regardless, heedless of the criticism, and deaf to the warnings. The complaints and discontentment expressed were nothing but pinpricks upon the flesh of the omnipotent King answerable only to God, or so it appeared.

Some undoubtedly prospered during the eleven years of his personal rule. It was a time of Royal largesse and those who were his most loyal supporters were well rewarded with titles and land grants. Efforts were also made to eradicate unemployment, roads were improved, and it was a time of peace that saw the growth of a commercial middle class, but it was exactly these people who objected to the King’s prerogatives in commerce.

It was his religious policies however that provoked the most resistance to his rule. He was a committed Protestant but like James and Elizabeth before him he believed in the trappings, ceremony, and grandeur of the Church. The spectacle of the religious service lay at the core of the Church of England. To many, particularly the Puritans, these were the remnants of Catholicism and little short of idolatry. Nonetheless, Charles was determined to impose religious uniformity throughout his Kingdom.

On 23 July 1637, a riot occurred when the Bishop of St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh tried to read from the recently published New Book of Common Prayer. It had been introduced into Scotland by William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had been instructed by Charles to enforce his policy of religious uniformity. The Scots viewed it as an attempt to impose an Anglican liturgy upon a Presbyterian people and thereby usurp their own Covenant with God. The violent opposition to it was sealed with the signing of the National Covenant on 28 February 1638.

Despite protestations of loyalty to the person of the King by those who opposed his religious reforms Charles was not willing to compromise with those involved in events that he did not perceive as a protest but as an act of rebellion and an assault upon his authority - he was determined to crush them.

It soon became apparent however that he had not the means to do so. An attempt to impose his will ended in farce when a Scottish Army marched south and defeated the English at the Battle of Newburn and occupied much of north-east England including Newcastle and its valuable coal supplies. Against his better judgement a humiliated Charles was forced to re-call Parliament.

Charles who had ruled without recourse to Parliament for more than a decade now needed them to raise the money to crush the rebellion that his policies had begun; but he soon discovered that it was not the Scottish aggression which preoccupied the Members of the House but the grievances that had accrued during his eleven years of personal rule and under the leadership of John Pym they now sought to curtail his powers so that he could never govern without them again.

For the first time Charles was forced to make concessions to those he had previously dismissed whenever it suited him. One of the first acts of the new Parliament on 18 December 1640 was to impeach the man who had been responsible for the imposition of the King’s religious reforms, the Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, who was placed under arrest in the Tower of London. Then in February 1641, they secured their own position by forcing the King to sign into law the Triennial Act which guaranteed a Parliament must be called every three years.

On 22 March, Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, former Lord Deputy of Ireland and the King’s strongman who had insisted that he take a hard-line with Parliament and had threatened to use an Irish Catholic Army to restore order if necessary was arrested on charges of high treason. Pym could not provide the proof of such a heinous crime and so had him charged under a Bill of Attainder that only required a suspicion of guilt, but it would also require the signature of the King. Charles informed Strafford that regardless of the verdict he would never sign it but requiring the continued support of Parliament he was given little choice. On 12 May, Strafford went to the scaffold. For a King who placed loyalty above everything else it was a shameful act for which he never forgave himself, and he was to come to believe that his own execution eight years later was God’s punishment for betraying a friend.

That same month Charles was forced to give Royal assent to acts that prevented Parliament from being dissolved without its own consent and saw the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission that dispensed the King’s justice abolished. A little later the Tonnage and Poundage Act forbade him from raising taxes of his own volition.

Charles, who had always considered himself above the grubby world of politics, was beginning to see his power swept away in a torrent of hostile legislation. His personal rule had come to an end, he had seen his closest friends and advisors arrested or executed and his authority undermined at every turn. He was losing control of the situation, the country, and the crown bequeathed him by his father. And things were about to get even worse.

On 23 October 1641, the Catholic population of Ireland rose in revolt, they claimed in reaction to the execution of Strafford and in support of the King. The horror stories of massacres committed on Protestants in Ireland were circulating on the streets of London within days and they placed the blame for them, false or exaggerated as many of them were, firmly at the door of the King.

Despite everything, Charles still retained considerable support in the House of Lords and many of the votes in the Commons that had gone against him had been close run things with high levels of abstention. This led Sir Edward Hyde, the future Lord Clarendon, to believe that the King could still win the argument politically and that many of the measures passed could be reversed in the fullness of time. He counselled caution but others most prominent among them, Henrietta Maria demanded that he, use force to re-impose his authority.

The relationship between Charles and Henrietta Maria had improved markedly following the assassination of the Duke of Buckingham. It appeared that he not only poisoned the relationship between the King and his Parliament but also between the King and his Queen. Indeed, they became devoted to one another and were in many respects the model Stuart family. The Royal Court had been transformed, the late-night parties, the drunkenness, the wild dancing, the unbridled flirtation were all a thing of the past. The deal makers and hangers-on had been banished. Charles and Henrietta Maria lived modestly if in great splendour, their household was a place of moral rectitude, and they were true to their religious devotions. The problem was that Henrietta Maria’s religious devotions were Catholic. She may have been an enemy of Buckingham’s but that did not make her a friend of Parliaments. She may have been modest in her behaviour, but this did not endear her to the Puritans. As far as they were concerned, she did not fulfil the role of the obedient wife, she was loud, overdressed, and meddlesome. Such was her unpopularity with Londoners that Charles was forced to curtail her journeys into the city for her own safety. About this she couldn’t have cared less because as she often repeated to anyone who was prepared to listen, she was not just the happiest woman in the world but the happiest woman who had ever lived. She was also now the dominant influence in her husband’s life.

Rumours were circulating in the corridors of Parliament that John Pym and his supporters intended to introduce a Militia Ordinance that would wrest control of the army from the King’s hands and permit Parliament to raise one of its own. It was also being suggested that they intended to begin impeachment proceedings against the Queen.

If a Militia Bill were passed, then the King would not even be able to secure the safety of his own family. Henrietta Maria demanded that he act, there had been too much talking with people not worthy of His Majesty – he must re-impose his authority by force of arms. Some tried to dissuade him from embarking upon such a drastic course of action, but this was advice that Charles, who had proven himself such a failure in the grubby world of politics, could understand.

On 4 January 1642, King Charles I entered the Chamber of the House of Commons alone except for a few retainers as 400 troops of the Royal Guard surrounded the building and waited outside its doors. He had in his hand a warrant for the arrest of five Members of Parliament – John Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig, and William Strode.

The King removed his hat in a sign of respect and requested the use of the Speaker William Lenthall’s chair. A witness to events describes what happened next:

“His Majesty came unto the House and took Mr Speaker’s Chair. (Then he said) Gentlemen, I am sorry to have this occasion to come unto you. (Then) when looking about the House, the Speaker standing below, by the Chair, His Majesty asked him, whether any of these persons were in the House? Whether he saw any of them? To which the Speaker, falling on his knee, thus answered: May it please Your Majesty; I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place, but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here; and humbly beg Your Majesty’s pardon, than I cannot give any answer than this to what Your Majesty demands of me.”

Placing his hat upon his head the King remarked, “It appears the birds are flown”, and with that he stormed from the Chamber still clutching the warrant in his hand and to the jeers of the Members ringing in his ears.

All of the Members named in the arrest warrant had indeed been in the Chamber right up to the last moment, but they had been forewarned of the King’s intentions, probably by Lady Carlisle who was a member of the Royal Court and had fled by boat into the City of London.

The King’s desperate gamble had failed and London, a city of strong Puritan and radical sentiment now rose in tumult. So much so that a week later 10 January, the King fled his own capital city with his family, first to Hampton Court and then onto Windsor Castle - the Rubicon had been crossed and the battle lines drawn.

The King’s Nemesis once the collective opposition of his own Parliament would soon become personified in the figure of one man – Oliver Cromwell.

Oliver Cromwell was born in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, on 25 April 1599, a year earlier than his future opponent in all things Charles Stuart, but it seemed proximity of age was the only thing they had in common.

He was from a family of minor gentry, respected in the local community but one that had known better times, and Oliver was its poor relation. The family finances were always run on a tight budget, but they were sufficient to send the young Oliver to the local Grammar School and later Cambridge University. He did not excel academically and proved better at sports and the more manly pursuits. His education was to be curtailed in any case when his father died leaving him responsible for the household and family estate.

It was a struggle from the outset though his fortunes improved somewhat when in 1620 he married Elizabeth Bourchier, the daughter of a wealthy London leather merchant.

Life was a struggle for Oliver not only had he to feed his rapidly expanding family but no less important was the need to maintain his status.

The burden only increased over time and by 1628, he was also supporting his widowed mother and his six unmarried sisters. He neither had the means to do so nor a network of support that could provide help in difficult times.

He was desperate to marry off his sisters but would be required to provide a dowry for each one and so as his status gradually declined so did their marriage prospects. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, he fell into a deep depression and thought for a time that he was dying. Advised to do so he visited the King’s physician Dr Theodore de Mayerne in London who diagnosed melancholia and suggested rest; but when Oliver had to work every hour available just to make ends meet this was out of the question. In the end, feeling no better, he had to return to the flat landscape and low, dark, oppressively heavy skies of the Fens.

As a member of the county gentry Oliver served upon Huntingdon Town Council. He already had a reputation as a hothead and as a man who struggled to keep his emotions in check when in 1630, he turned a minor dispute into a major row during which he insulted the Town Mayor. He was forced to make a public apology at the next Council meeting before being dismissed from it altogether.

Not long after this public humiliation Oliver sold the family estate for around £1,800 and moved to nearby St Ives where he rented a farmhouse and some land becoming in effect a Yeoman Farmer. He now had to work the land with his own hands. His long struggle to maintain his status was failing and he was falling out of the class into which he had been born.

Cromwell’s life appeared to be in terminal decline, and he was often ill taking frequently to his bed. He was saved it seems, spiritually at least by a local firebrand Puritan preacher named Jo Tookey who convinced him that his troubles were God testing him and that it would be his personal relationship with God that would prove his salvation.

This may have been so but it was to be the death of an uncle on his mother’s side in 1636, Thomas Steward that was to save him materially. He had died childless and as his closest living male relative Oliver was left both land and a number of properties in nearby Ely. His inheritance saw him suddenly and unexpectedly restored to his previous status. Oliver saw it as a sign of God’s blessing. On 13 October 1638, he wrote to his cousin Elizabeth St John: “You know what my manner of life hath been. Oh, I lived and loved darkness, and hated the light. I was a chief, the chief of sinners. This is true; I hated Godliness, yet God had mercy on me. O the riches of his mercy! Praise Him for me, pray for me, that He who hath begun a good work would perfect to the day of Christ.”

It was a classic story of religious conversion for Oliver who had rarely been, or ever would be, the personification of Godliness. He was rather a man of violent mood swings, deeply emotional and easily reduced to tears. He liked to dance, to drink, and to smoke, and had a fondness for rather childish practical jokes. It is not how we imagine a Puritan to be, but his religious commitment was in earnest, sincere, and deep, and he constantly fretted about his relationship with God. He was to prove as hesitant in politics as he was decisive in war because he would not act without God’s blessing and God’s will was made clear in battle in a way that it never was in the world of discussion, dispute and debate.

Oliver’s wife, Elizabeth, provided the stability he lacked and unlike Henrietta Maria she did fit the template of the good seventeenth century wife. Moreover, she was a Puritan wife. She dressed modestly, spoke rarely in public, deferred to her husband in all things and paid close attention to her woman’s domain of hearth, home, kitchen, and the raising of her children.

She kept an orderly house in stark contrast to her husband’s often disorderly mind and erratic behaviour.

In 1640, Oliver was elected the Member of Parliament for Huntingdon and attended the sessions of the Long Parliament. He only spoke once in the House in a speech that was not particularly well received. He neither looked nor spoke like a gentleman and played only a minor role in the momentous events then taking place being primarily concerned with the rights of his tenants and questions of land ownership but his zeal was noted.

Someone wrote of his appearance at that time: “I perceived a gentleman, very ordinary, apparelled, he wore a plain cloth made by an ill country tailor, his linen was not very clean, his countenance was swollen and reddish, his voice was sharp and untunable, his eloquence full of fervour.”

Oliver never cared much for his appearance and on his first day in the House he appeared with blood on his shirt having cut himself shaving. But he threw himself into parliamentary activity with a violent enthusiasm unsuited to the task being named on various committees. Yet the more noise he made the more he was ignored and in truth he made little impact. He simply wasn’t very good at it, his violent tongue and red-faced table thumping fury were largely ignored in the gentler arenas of debate. It would be as a soldier, a leader on the blood-soaked battlefield of war that he would come into his own, stake his claim to greatness, and become the King’s worse nightmare.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: