The Lancastria: Churchill's Dark Secret

Posted on 30th June 2021

More than two weeks after the successful evacuation of British forces from the beaches at Dunkirk some 145,000 British servicemen remained stranded in France. They were not for the most part front-line troops but members of the Pioneer Corps, the Catering Corps and Royal Air Force ground crew.

With it clear to everyone that the French Army was close to collapse and capitulation only a matter of time those British forces in South-West France were ordered to make their way to the port of St Nazaire, and to do so with some haste.

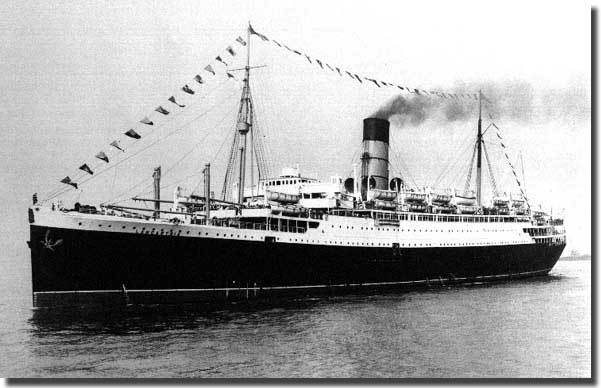

On 14 June 1940, the R.M.S Lancastria, a Cunard liner with room for 2,200 passengers and a crew of 375 was ordered to leave Liverpool and head for St Nazaire. She had been requisitioned as a troopship in April 1940 and had already been used to evacuate troops following the disastrous campaign in Norway and had only recently returned from Iceland.

Her crew felt they were due for a break but instead they had received orders to participate in Operation Ariel, the evacuation of the last remaining British troops in France. She made good progress and by 16 June was anchored some 11 miles off the French coast in the Loire estuary.

That night she began embarking thousands of troops and civilians but there was no time to count everyone who was coming aboard or detail who they were and estimates of the numbers who eventually boarded vary from anything between 4,000 and 8,000 people.

The Lancastria's Captain Rudolph Sharp had been told to forget about any safety issues and simply get as many people aboard as he possibly could, and the ship was soon packed to the gunnels.

Civilians, including many children were issued tickets indicating their cabin and deck numbers whilst the soldiers were simply herded into the ships vast cargo holds. Many were exhausted and were asleep within minutes others more nervous chose to remain upon deck.

The Lancastria was still loading people aboard when at around 13.00 on 17 June German Heinkel Bombers appeared overhead and attacked the liner Oronsay. Although the Oronsay was some way off those on the deck of the Lancastria could clearly see what was happening until a direct hit on her bridge saw her shrouded in smoke and disappear from view.

Although badly damaged the Oronsay continued on her way and managed to limp back to England but those aboard the Lancastria knew they would be next.

Captain Sharp now ordered an end to the embarkation but refused to leave without a destroyer escort despite being repeatedly advised to do so. He also did not order the Lancastria to steam ahead or circle and instead she remained static in the water making her a sitting target.

Meanwhile, the tension aboard the ship was palpable for everyone knew that the Germans would be back.

At 15.50 that afternoon the Heinkels returned and headed straight for the Lancastria and she was soon being straddled by bombs one of which exploded close to her port side rupturing her fuel tanks and spilling thousands of gallons of thick, suffocating oil into the sea around her. Fires also erupted which sent a plume of dense black smoke high into the sky.

Moments later a bomb penetrated the cargo holds that were crammed with thousands of soldiers.

It had destroyed the exit to Cargo Hold No 2 trapping 800 R.A.F maintenance crew and plunging much of the ship into darkness. Panicking troops and civilians now stumbled around in the darkness and the choking smoke clambering over shattered timber and each other in a desperate attempt to find a way out.

Many of the soldiers on deck who decided to abandon the ship early and leapt into the sea from a great height either forgot, or were unaware, of the instruction to bend their legs to absorb the impact of the water and to push hard-down upon their lifejackets to prevent them from rising and breaking their neck.

The sea was soon littered with the lifeless bodies of men their heads hanging loosely making one survivor describe them as looking like so many coconuts.

Much of the bottom of the Lancastria had been blown away, water was flooding in and just a few minutes after the attack had started, she groaned, shuddered, and began to sway in the water before rolling over onto her side. There had been little time to lower the boats and though Captain Sharp had initially ordered that it be women and children first it was soon changed to every man for himself.

Many of those who had managed to clamber over the side of the ship and into a lifeboat could see through the portholes the horrifying sight of those still trapped inside and unable to get out. German fighter planes now added to the horror by returning to strafe those hundreds of men still clinging to the ship and those struggling in the water. They were also trying to set alight the oil that surrounded the doomed ship.

At 16.10, just twenty minutes after first being attacked the Lancastria sank taking those soldiers who could not swim and were desperately still clinging to her hull and the thousands who remained trapped inside down with her.

Many of the soldiers struggling in the water who had been ordered not to relinquish their kit under any circumstances refused to do so even now and weighed down and exhausted many now simply gave up the fight and drowned.

Where just before the crew of the ships nearby could hear those on the upturned hull defiantly singing Roll out the Barrel there was suddenly silence; some of those rescued from the sea would later say they could still hear voices long after the ship had disappeared.

Some 2,477 survivors were rescued with more than 900 being plucked from the sea by the trawler Cambridgeshire.

The official death toll of those who went down with the Lancastria is 1,738 though the true figure is believed to nearer 4,000 and for months after bodies regularly washed up on the French shoreline.

The sinking of the Lancastria was the greatest disaster in British maritime history, and one that the Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whom it was said wept at the news, was desperate to cover up. He was wary of harming the new spirit of defiance that had emerged since the ‘Miracle of Dunkirk.’ And so, he ordered a ‘D Notice’, or embargo, be placed on any reporting of the tragedy and that those who had survived the sinking or had participated in the rescue were ordered not to speak of it. But it could not remain a secret for long.

On 26 July, the loss of the Lancastria was reported in the New York Times and a little later in the Scotsman Newspaper. The Daily Herald even put the story on its front cover with harrowing photographs.

The Government however remained silent on the issue and once the initial flurry of reporting had passed it was never again spoken of. This official silence was to continue for more than sixty years and until the final resting place of the Lancastria was officially designated a war grave in 2010.

Captain Sharp, who survived the sinking of the Lancastria went onto command the troopship S.S Laconia during one of the most notorious events of World War Two.

The controversial Laconia Incident occurred on 12 September 1942 when it was torpedoed and sunk by U.156 off the coast of West Africa whilst transporting mostly Italian prisoners-of-war to Internment Camps in Canada.

The Captain of U.156 Werner Hartenstein surfaced, lowered boats and summoned help in the rescue operation from other U-Boats and Allied warships in the vicinity on open radio.

Whilst the rescue was underway, they were attacked by an American B.24 Bomber and it had to be hastily abandoned.

Following this the Commander of the German U.Boat Fleet Grand Admiral Donitz issued the Laconia Order forbidding U-Boat Captains from assisting the survivors of any sinking and thereby putting their own vessels at risk. In issuing the Laconia Order, Donitz was accused of having committed a war crime at the Nuremburg Trial, but he was cleared of the charge.

People who knew him said that Captain Sharp felt an intense guilt at having survived the sinking of the Lancastria. Now having ensured that the great many women and children who were also aboard the Laconia had been lifted into the lifeboats first he returned to his cabin and went down with the ship.

More than 1,600 people went down with the Laconia. It is the second greatest disaster in British maritime history.

Share this post: