The Major-Generals

Posted on 15th January 2021

On 12 December 1653, following the dissolution of the Bare Bones Parliament (so-called after John Barebone a London Leather maker and ardent Fifth Monarchist whose sharp Religiosity made a change from the endless politicking of most) Major-General John Lambert, a close ally of Oliver Cromwell, introduced a new Constitution known as the Instrument of Government in which he proposed his old friend should be appointed Lord Protector and Head of State. Cromwell was already de-facto ruler of England through his command of the army, but this would make his rule official.

He had earlier rejected the offer of the Crown believing that having deposed and executed the previous King to do so would be in opposition to the Will of God. Four years later following the passage of the Humble Petition and Advice he was to be offered the Crown again, and again he rejected it. He liked the idea of Lord Protector though, and on 26 June 1657, four years after becoming so he made it official in a ceremony that had all the trappings of a Coronation. But when Lambert proposed the title be a hereditary one it was voted down in Parliament, including by members of Cromwell’s own family.

Cromwell had long used his command of the army to bully, intimidate, and dissolve various Parliaments now as Head of State he made his priority the “healing and settling of the country,” but this was easier said than done.

England was a country awash with conspiracy, at least it was as far as Cromwell was concerned and in this at least his suspicions were not unfounded. Royalist organisations remained active in England. The two most significant were the Sealed Knot and the more militant Action Party. Both sought the restoration of the Stuart Monarchy and were in regular contact with the agents of the exiled heir to the throne in Paris.

Cromwell was aware of the activities of these groups through a sophisticated and elaborate spy network run by John Thurloe, and many of his so-called Intelligencers had infiltrated these groups and maintained a stream of information that allowed the Government to remain one step ahead of the rebels and nip in the bud most attempts at insurrection before they could gain momentum.

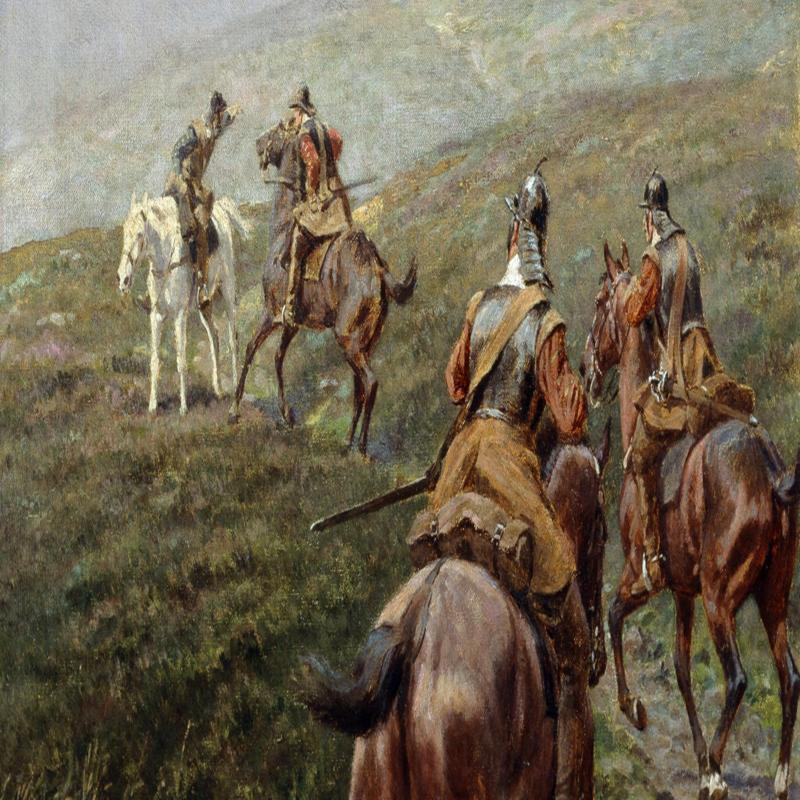

It was usual at the first sign of trouble for leading Royalists and those known to have fought for the old regime in any area to be detained but despite keeping a tight rein on things they were not always successful.

As dusk settled on 8 March 1655, The Earl of Rochester led 300 Royalist insurgents onto the old battlefield at Marston Moor near York. A little later they marched on the city but when it refused to open its gates to them panic set in and they quickly dispersed. Despite the somewhat farcical outcome of the rising in Yorkshire it was actually the first stirring of what was intended to be a nationwide Royalist insurrection, but it was reliant upon the support of the people and when this did not materialise, they were left out on a limb with nowhere to go. Similar scenarios were now played out elsewhere. All except that was in the West Country.

On 11 March, Colonel John Penruddock gathered his forces, some 400 men, a few miles south-east of Salisbury. In the early hours of the following morning, he occupied the town capturing a number of prominent Judges and the High Sheriff of Wiltshire. He intended to use these as hostages. He then read out a proclamation declaring himself for King Charles II and calling upon the people to support him and rally to the King. When they failed to do so he embarked upon a hasty tour of the surrounding area in a desperate attempt to drum up support.

The West Country had remained a stronghold of Royalist support throughout the Civil War. If the people, there would not rise and fight for the Restoration of the Monarchy then they would not do so anywhere.

Cromwell was quick to react to the news of the uprising in the West Country and on 14 March Government forces under the command of Major-General John Disbrowe caught up with the rebels and after a brief but bloody skirmish the rebels were defeated and Colonel Penruddock captured. He was later executed.

Despite Penruddock’s death and the insurrection elsewhere petering out of its own accord, it was for Cromwell the last straw. He believed he acted according to the Will of God and saw failure on his part to be a sign of the Lord’s displeasure. If there were people who still wished to see the Restoration of the Monarchy. Even after God’s Will had been so clearly expressed in the defeat and execution of the King then it was because he as Head of State was not leading them on the path of righteousness. The country needed a moral cleansing. If people could not be trusted to govern their own behaviours, then he would do it for them. He would introduce direct military rule and the country would be governed by Major-Generals who would enforce strict codes of moral conduct. If the people infringed these codes, then they would be punished accordingly.

In any case, Cromwell had long despaired of politicians and of the institution of Parliament which they polluted with their presence. All they did was squabble and try to serve their own commercial interests rather than do God’s work. If they were incapable of propriety and hard work then he would dispense with them and on 31 October 1655, he declared the rule of the Major-Generals.

The country was divided up into 12 regions each to be governed by a Major-General answerable only to the Lord Protector himself. First and foremost, they were to be responsible for security, after all Cromwell saw Royalist plots everywhere and in everything. The Major-Generals were to raise their own Militia to enforce law and order. This was to be paid for by a 10% decimation tax on known Royalist sympathisers. As far as Cromwell was concerned his attempt at reconciliation with the Royalists had failed and from now on they would be put under surveillance, they would require permission from a the Major-General to travel, and would have to declare the names of anyone who visited.

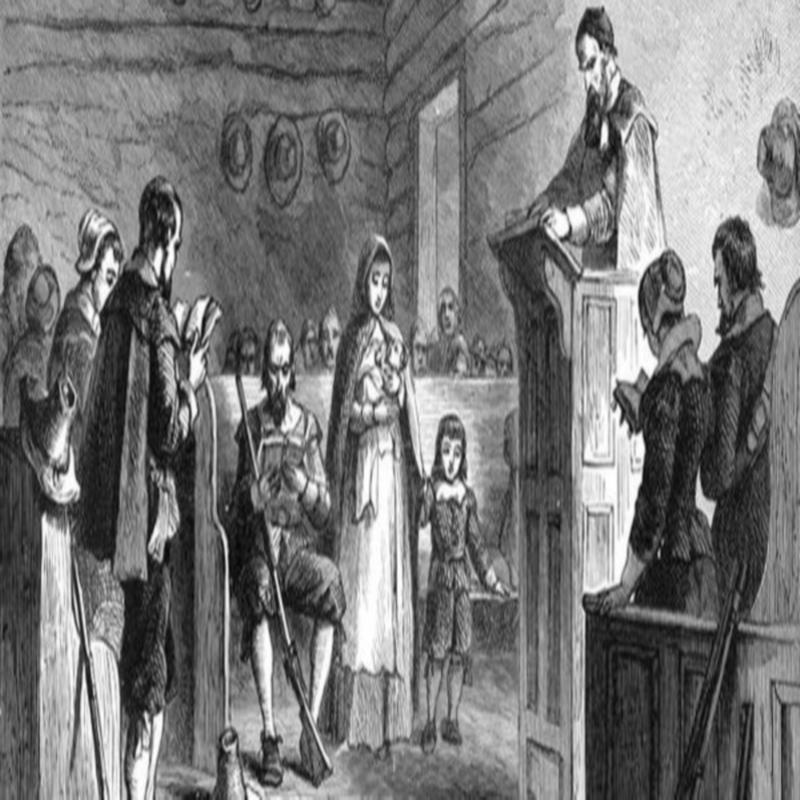

It was not to be the clampdown on suspected Royalist activity that made the Major-Generals notorious however, but their attempt to impose a new morality upon the people. Popular pastimes such as horse racing, cockfighting, bear-baiting and the staging of plays were banned, as was indeed the playing of football. Public drunkenness would result in a day in the pillory without food and water and on the spot, fines were imposed for swearing and blasphemy. Church attendance also became compulsory especially on a Sunday and local Pastors were expected to supply the names of those of their congregation who did not attend regularly.

The Major-Generals however had to work with local Constables and Magistrates who were no keener than anyone else to have restrictions imposed upon their behaviour and were unwilling to implement draconian measures for what they perceived as some minor infringement of a ridiculous code of conduct. Indeed, so trivial were some of the punishments imposed that the Major-Generals soon became a laughingstock and wrote with increasing frustration to Cromwell that the local Authorities were not treating them seriously.

Much more dangerous for the moral crusaders in Parliament than any bullying by the Major-Generals however was their abolition of Christmas. In June 1647, the Long Parliament, so known because it had sat since before the start of the Civil War, had begun the process of clamping down on festivities with the introduction of the Directory of Public Worship and the declaration that Sunday would be the only holy day and there should no festivals linked in any way to religious worship.

The Puritans had long been ambivalent towards Christmas whereas some of the less fanatical saw merit in its religious observance others recognised it as at best a pagan festival and at worst a Catholic heresy. They all, however, despised the raucous celebration that came with it, the blasphemy, drunkenness, and public displays of lewd behaviour. The prevailing attitude of the Puritan to Christmas was best summed up in the book The Anatomy of Abuses by Thomas Stubbs in which he wrote:

“More mischief is that time committed than in all the years besides, what dicing, and carding, what eating and drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used, to the great dishonouring of God and the impoverishment of the realm.”

Enjoyment for the sake of enjoyment was not to be permitted. Christmas was no longer to be celebrated, there was to be no public holiday, trimmings were to be taken down, and shops and workplaces were to be forced to remain open.

Banning Christmas was the most unpopular thing the new Commonwealth ever did and became almost impossible to enforce. People regularly ignored the proscriptions on Christmas, towns continued to be adorned with decorations and when the Major-Generals tried to enforce the new rules riots resulted in London, Norwich, Bury-St-Edmunds, and many other places. In Colchester such were the levels of disgruntlement that it turned into a full-scale revolt which had to be bloodily suppressed after a prolonged siege of the town – the people might not have been willing to fight for the restoration of the Monarchy, but they were willing to fight for the restoration of Christmas.

Such was the resentment towards the rule of the Major-Generals and their ineffectiveness that the Army hierarchy feared that they were losing the respect of the people. Always sensitive to the feelings of the Army in March 1658, Cromwell abolished the role of the Major-Generals. His great attempt at a moral cleansing had ended in miserable failure.

Upon the Restoration of the Stuart Monarchy on 8 May 1660, one of the first things the new King Charles II did was to reinstitute Christmas, earning him not only the gratitude of the people but the title thereafter of the Merry Monarch.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: