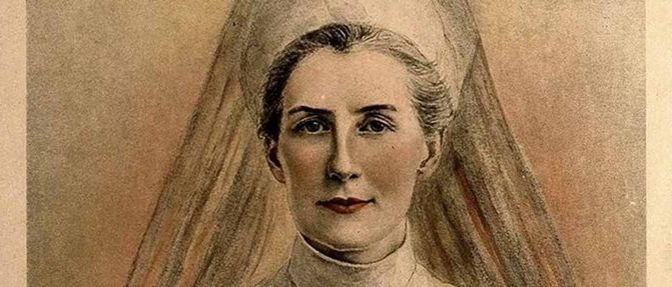

The Martyrdom of Nurse Edith Cavell

Posted on 26th June 2021

Few incidents in World War One caused greater outrage or drew as much international condemnation as the execution of a middle-aged woman whose entire life had been spent in the scenic lowlands of her childhood and the obscurity of her profession.

She was to become a cause celebre, a valuable tool of propaganda and provide a legacy of everlasting martyrdom.

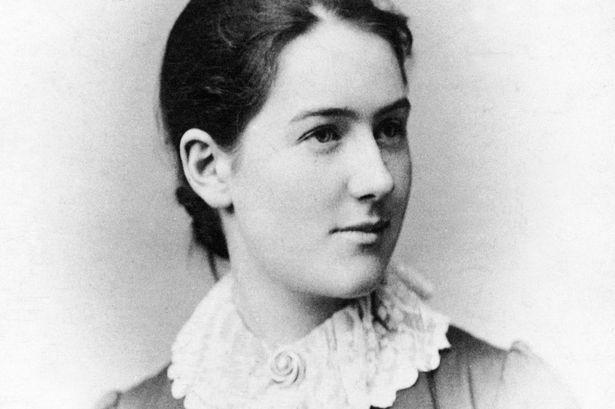

Edith Louise Cavell was born in the village of Swardeston near Norwich on 4 December 1865 the daughter of an Anglican vicar. Her upbringing was fairly conventional for that of a parson’s daughter though life at home could often be a little dull with music, dancing and the playing of games banned with her only permitted reading being the Bible.

Despite this Edith was a happy child and though her father Frederick was somewhat of a puritan he was a warm and loving man whilst her mother Louisa was a gentle soul dedicated to the rearing of her children and Edith and her three younger siblings were always free to find their entertainment outside of the home.

She always enjoyed the outdoors and became an accomplished artist painting the beautiful Norfolk countryside around her home. She also enjoyed raising funds for her father’s church and in winter would ice-skate on a nearby lake.

Educated at various boarding schools she proved a well-behaved and hard-working if not an outstanding student though she had a flair for French. Upon finishing school, she worked for a time as a teacher before she was recommended for the post of governess to the Francoise family in Brussels.

Despite not wanting to leave the family home she travelled to Belgium but even though she enjoyed her time as a governess in 1895 she returned to England to care for her ailing father and train as a nurse which was one of the few opportunities then available for women who wanted to pursue a career.

Often portrayed as a sober and serious woman of deep religious conviction Edith was not the dour old stick in the mud the many commentaries on her life have made her appear. She had a lively sense of humour, loved to dance and though she had never married she’d had a number of romantic dalliances.

During her time as a governess, she had been popular with the children under her charge and whilst training as a nurse she was just as popular if often distracted and rarely punctual.

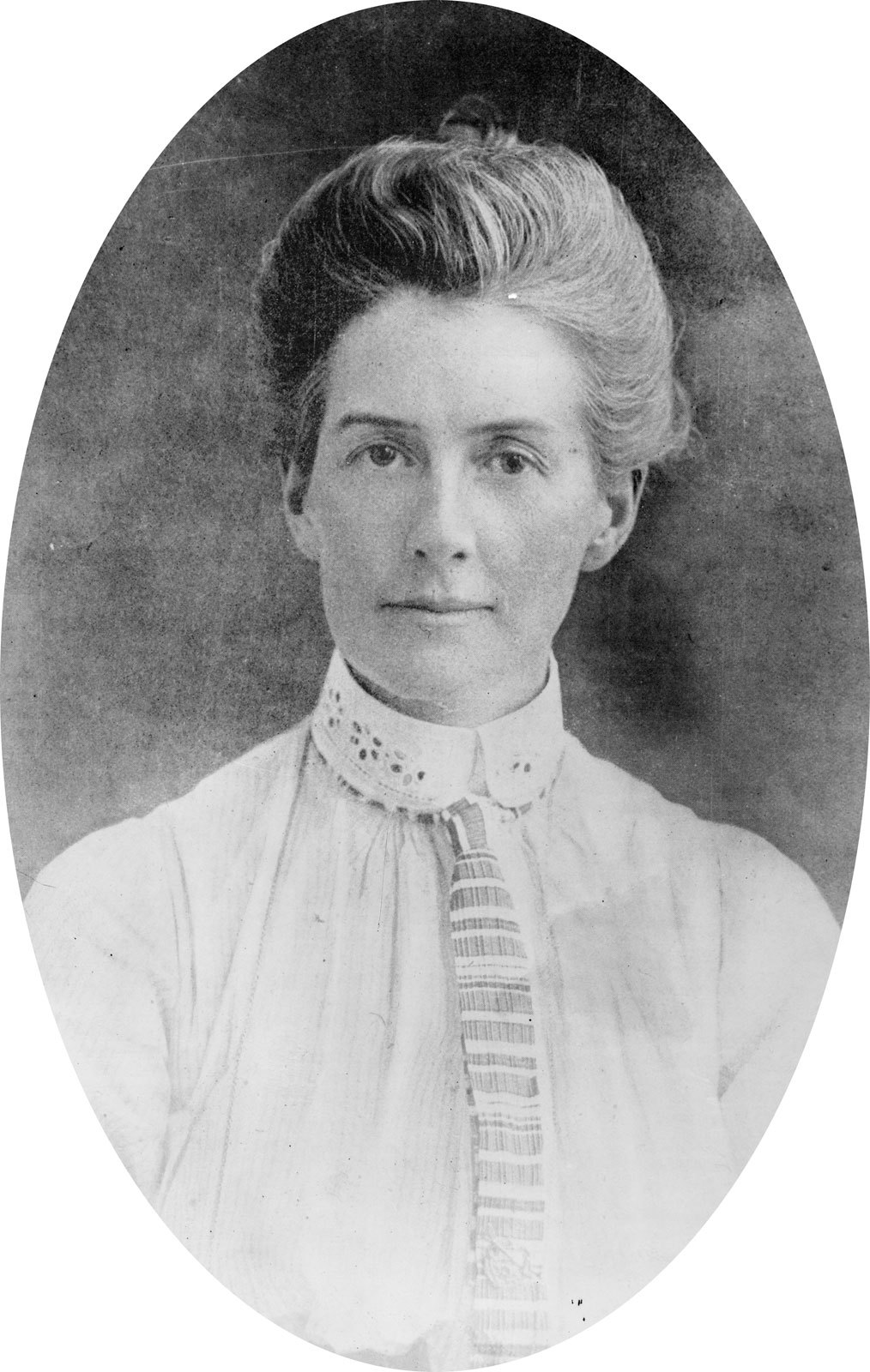

In 1907, she returned from Brussels to work as one of the trainers at the Belgian School of Registered Nurses where she was considered a hard but fair taskmaster.

Back in Norfolk visiting her family when news of the German invasion of Belgium broke, she determined to return to Brussels immediately declaring that her duty lay with her nurses despite being warned of the dangers of doing so.

The clinic where she worked soon became a Red Cross Hospital tending to the wounded of both friend and foe alike. Indeed, Edith gave strict orders that all wounded soldiers must be treated the same regardless of nationality.

In the autumn of 1914, the Germans occupied Brussels and within a few months an underground organisation had formed to help stranded Allied troops who were trying to find their way back to their own lines. They would be provided with false papers by Prince Reginald de Croy at his Chateau near Mons before being taken to safe houses where guides would spirit them across the Dutch frontier.

Working closely alongside the Belgian architect Philippe Baucq, Edith began sheltering British troops and providing them with money and she is known to have helped at least 200 of them to safety.

The Germans became aware of what was going on and began to suspect Edith when several the British soldiers who she was known to have nursed could not be accounted for. Their suspicions appeared to be confirmed when a series of incriminating letters were handed to them by a colleague Gaston Quien, who would later be charged with treason by the Belgian Authorities.

Questioned by the Germans her propensity for straight-talking and total disregard for her own safety did little to help her cause. Advised by her friends to flee she refused saying that she could not stop while there were lives to be saved. On 3 August 1915, she was arrested and charged with harbouring allied prisoners-of-war.

Under interrogation Edith said little in her own defence and at one point even appeared to confess to all the charges, though it has since been suggested that she was tricked and told that no harm would come to her or her associates if she did so.

Following her confession, the trial was little more than a formality and both she and Philippe Baucq were found guilty under law 58 and 90 of the German Military Code or aiding a hostile power and of conducting soldiers to the enemy. The sentence for which was death.

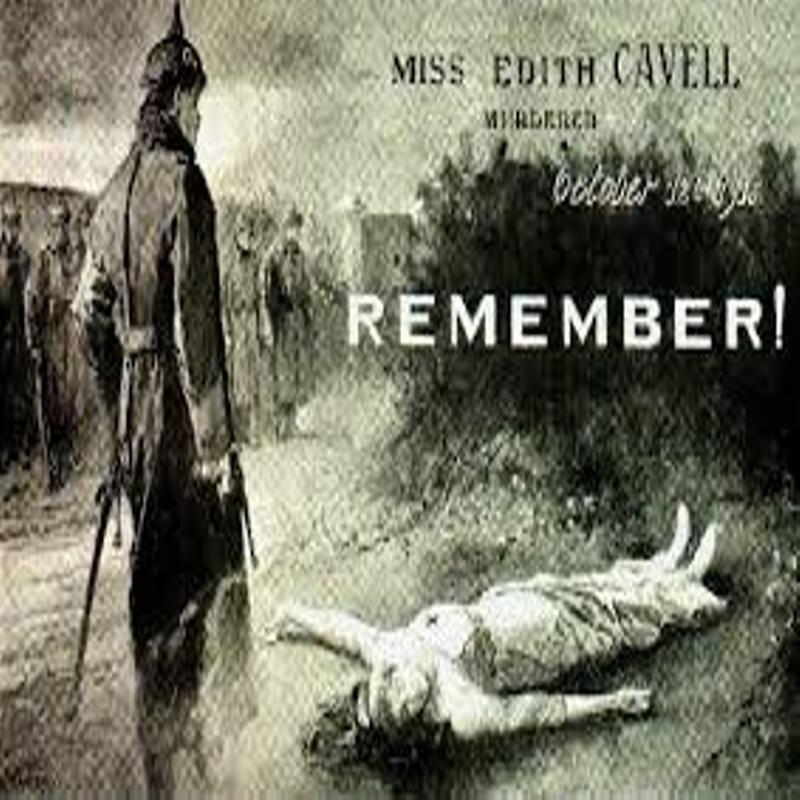

The death sentence passed made headlines around the world and the British propaganda machine milked it to the full. The Government, however, refused to intercede on her behalf fearing that to do so would merely hasten the sentence being carried out.

The United States were not so reticent however, and the American Attache in Brussels Hugh Gibson met with the Civil Governor Baron von der Lancken to tell him of his country’s disapproval and how such a murder would stir all civilised countries to anger and disgust. At which point a German representative at the meeting, Count Harrach angrily interjected: “I would rather see Miss Cavell shot. I only regret that there are not three or four more old English women to shoot.”

Yet another accusation of the Beastly Hun so soon after the Lusitania debacle only further infuriated the Germans and the Military Commander in Brussels General Trottgaut von Sauberzweig now demanded that the execution be carried out immediately.

Baron von der Lancken was more inclined to mercy and requested clemency for Edith on the grounds of her apparent confession and for all the lives she had saved including those of a great many German soldiers.

The German military authorities were eager however to make an example of this wretched woman and all appeals for clemency, and there were many, were ignored.

The Germans were in fact behaving according to their own rules of war and their actions did not contravene the Geneva Convention which protected medical staff but only in their role as non-belligerents and Edith, who had it was later revealed been recruited by the British Secret Intelligence Service had undertaken wartime activity. But hiding behind due process of law was not enough to justify the execution in the eyes of the world.

Edith, who was to spend the last two weeks of her ten-week incarceration in solitary confinement spent a great deal of her time in quiet reflection writing letters home and reading the Bible. She was not afraid to die and wrote: “I have seen death so often it is not strange, or fearful to me.”

After receiving Holy Communion from the Reverend Stirling Gahan, she told him: "Standing in view of God and Eternity, I realise that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

On 12 October 1915, Nurse Edith Cavell was led from her prison cell to her place of execution.

Described as being serene at the moment of her death she met it with great calmness and an assured equanimity, though the German soldier responsible for blindfolding her later said she had tears in her eyes. Having already forgiven those who were responsible for her execution her last words spoken to the Lutheran Pastor attending her were: “Tell my loved ones that my soul is safe and that I am glad to die for my country.”

Executed with Edith that day were Philippe Baucq and several others..

In the days following Edith’s death the German Minister for Foreign Affairs Arthur Zimmerman tried to defend the decision to execute her writing in an open letter: “It is undoubtedly a terrible thing that a woman has to be executed; but consider what would happen to a State, particularly one at war, if it let crimes go unpunished because they were committed by women.

Countless Belgian, French and English soldiers are again fighting in the ranks of the Allies who owe their escape to the activities of these people who were found guilty, whose head was the Cavell woman.”

It did not help.

propaganda disasters for the Germans and it was easy for people to believe stories such as that of the crucified soldier nailed it was said to a church door in mockery of Christ.

The cold-blooded murder of a nurse who dedicated her life to saving the lives of others merely reinforced the widely held that there was no act of depravity that the Beastly Hun would not stoop to in pursuit of his ends.

Edith Cavell had become a martyr and, in the months, immediately following her execution recruitment in Britain more than doubled.

Following the end of the war Edith Cavell’s body was repatriated to Britain where with all the trappings of a State Funeral it was taken in procession to Westminster Abbey and in a solemn ceremony presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury and attended by members of the Royal Family a plaque was dedicated in her name.

In May 1919, her remains were interred in Norwich Cathedral where a memorial was built to her memory. Other such memorials also stand in St Martin’s Lane in London and at her place of execution at Schaarbeek in Brussels.

Share this post: