The Nazi Olympics

Posted on 23rd August 2021

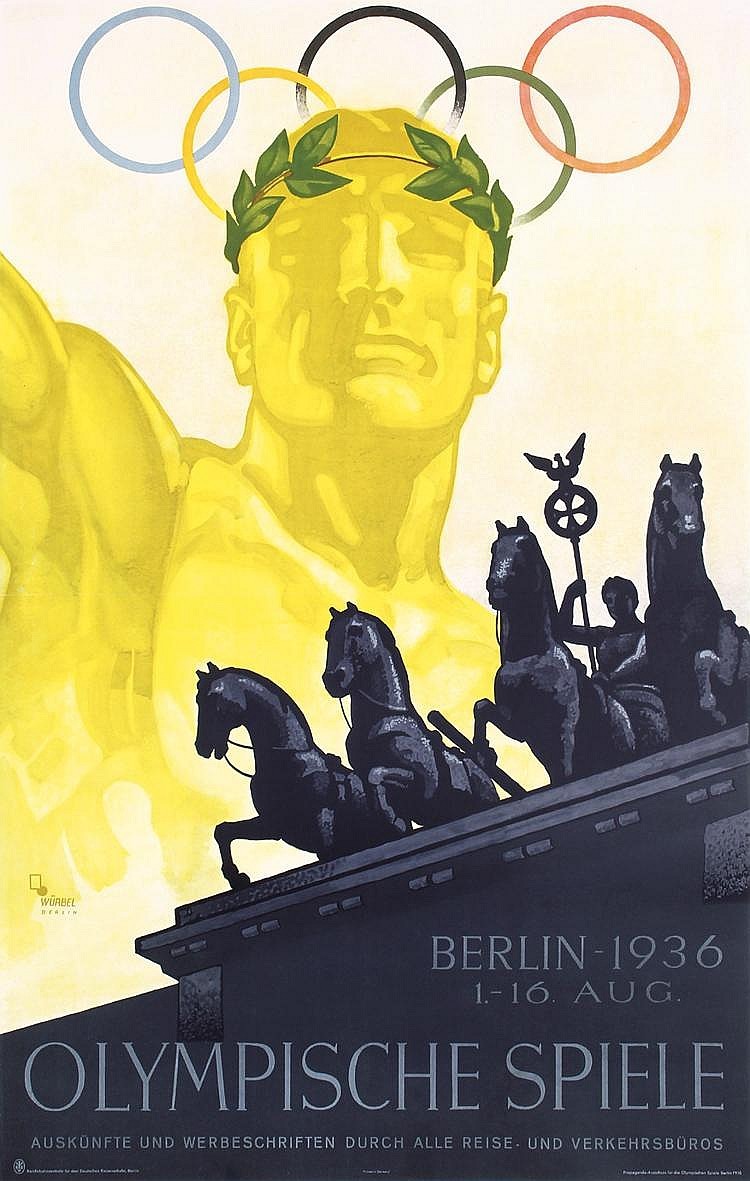

The Games of the XI Olympiad set to take place in the summer of 1936, were awarded to Berlin in Germany on 26 April 1931, nearly two years before the Nazi’s came to power and at a time when there still seemed little prospect of them ever doing so. It was still less than twenty years since the end of the carnage of the Great War for which Germany had been subsequently blamed and sport was seen as a means of reconciliation, of bringing people together - and the greatest sporting show on earth was the Olympic Games.

Prior to Hitler becoming Chancellor in January 1933, the Nazi’s were largely an unknown quantity outside of Germany and many people were initially impressed by the Fuhrer and his Nazi Government. They appeared to bring order where previously there had been chaos, had stabilised the currency ending the nightmare of hyper-inflation and were solving the problem of mass-unemployment.

But doubts surfaced as the true nature of the regime became increasingly apparent.

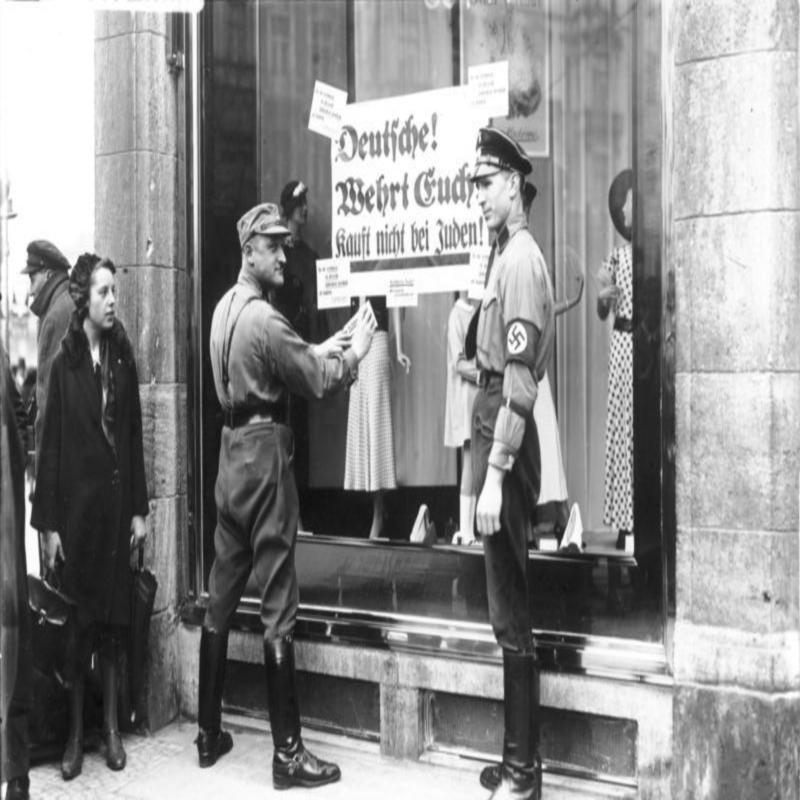

In April 1933, just eight weeks after coming into power the Nazi’s organised a nationwide boycott of Jewish shops and businesses. Brown-shirted SA men were stationed outside every Jewish owned establishment to intimidate potential customers and their windows were daubed with slogans such as “Jews Out” and “The Jews are our Misfortune.”

Much to the Nazi’s fury the boycott was largely ignored, and Germans continued to shop where they had always shopped, call upon their Jewish doctor and seek advice from their Jewish lawyer. But the boycott was just a sign of things to come.

On 30 June 1934, the Nazi’s decided to purge their political opponents and those they considered the enemy within in what was to become known as the - Night of the Long Knives. Its primary aim was to break the power of the Sturm Abteilung, or SA, the army of brown-shirted thugs that had done so much to bring the Nazi’s to power, but it would also provide the opportunity to eliminate those who had expressed opposition to the regime, and to settle a number of personal scores.

The official figure of those who were arrested and summarily executed without trial was 120. Among them were not only leading members of the SA including its leader Ernst Rohm but army officers, trade unionists, politicians and even an ex-Chancellor. The true figure was much higher however, and thousands of others were also rounded up and sent to concentration camps.

The executions were carried out on the express orders of Adolf Hitler who later justified his actions on the grounds that he was the Supreme Arbiter of the German people at times of national crisis.

But far as the rest of the world was concerned the Nazi Government which had previously cloaked itself in a spurious legality had exposed itself as a regime of murder that acted outside the law. In the meantime, the persecution of the Jews and other so-called undesirables continued.

On 15 September 1935, the Nuremburg Laws were passed which not only defined who was to be considered a Jew but already banned from working in the Civil Service, barred from the professions and not permitted to use municipal facilities they were now stripped of any remaining rights and finally of their German citizenship altogether.

Alongside the continuing persecution of the Jews other minorities were also targeted including gypsies and homosexuals and there was an active campaign to encourage Germans to denounce to the authorities those who expressed unorthodox views or behaviour.

Events in Germany did not sit easily with the Olympic ideal of using sport as the means to bring people of all nationalities, cultures and religious and ethnic background together in a spirit of friendship and fair play.

This was amplified further when the German Olympic Committee tentatively proposed that Jewish and black athletes be banned from competing but quickly backtracked when objections were raised. Nevertheless, moves were underway for a late change of venue, and there was even talk of a boycott.

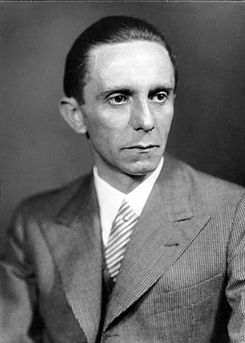

Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Enlightenment and Propaganda who was to play a pivotal role in organising the Games well understood their value, that there would never be a better opportunity to showcase Nazi Germany to the world, to promote their form of Government and to prove beyond doubt the veracity of their racial theories. The Berlin Olympiad must go ahead, and he would ensure it did.

Despite the Nazi’s attempts to deflect criticism many individual athletes expressed a reluctance to compete in Berlin and the campaign for a change of venue continued to gain momentum. It was dealt a fatal blow however, when on 26 September 1934, Avery Brundage, the Head of the American Olympic Committee who had previously expressed his admiration for Adolf Hitler and had already referred to a Jewish-Communist plot to prevent a United States team from competing in Berlin returned from a fact-finding mission to Germany to announce without consultation that they would attend and be honoured to do so. As the most powerful member of the International Olympic Committee most other countries now fell into line with only Spain and the Soviet Union refusing to attend.

Though the actual vote to confirm America’s attendance was close, Brundage’s announcement had effectively been a fait accompli.

Joseph Goebbels ensured that no stone was left unturned to guarantee that the Berlin Games would be the greatest sporting event known to history.

A purpose-built stadium with a capacity for 100,000 spectators was constructed in Berlin and the enfant terrible of documentary film-making Leni Reifenstahl, whose portrayal of the Nuremburg Rally had done so much to help create the Fuhrer Myth and the notion of Hitler as a Man of Destiny was commissioned to capture the event for posterity.

For the first time television cameras were strategically positioned throughout the stadium to guarantee that no moment of Aryan glory was missed.

Throughout Germany, anti-Jewish signs were taken down and graffiti daubed over, anti-Semitic journals were removed from news-stands and brown-shirted SA men were given a crash course in public relations and how to be nice to people.

The German people were to be on their best behaviour for the many hundreds of thousands of tourists from around the world who were expected to attend, and they even made great play of including a Jewish athlete in their team, the fencing champion Helene Mayer even though she had lived for many years in America and did not personally consider herself to be Jewish at all.

Despite the best efforts of the Nazi’s to burnish their image many athletes remained unhappy about competing in Berlin and an alternative Peoples’ Olympiad was arranged to take place at the same time as the Berlin Games in Barcelona and some 6,000 athletes had registered to attend considerably more than were going to the official Olympics. But the day before it was due to start there was a military uprising (the onset of the Spanish Civil War) and it had to be abandoned.

Prior to the Games starting gypsies, and itinerants were rounded-up and incarcerated in recently constructed Internment Camps, the streets cleaned, and the Olympic flag flown alongside the swastika in every major town and city.

The opening ceremony took place on 1 August 1936, before a packed and enthusiastic stadium with Hitler and the Nazi hierarchy looking on. The usual Fuhrer Weather was absent, and it was a grey, overcast and slightly chilly day.

For the first time the Games history the Olympic Torch had been carried by a relay of athletes all the way from Mount Olympus in Greece with the honour of carrying it into the stadium and lighting the flame falling to Siegfried Eifrig - tall, blond and blue-eyed, the very personification of Aryan man - the Nazi Olympics had begun.

Leni Reifenstahl caught every moment on camera and the stadium was dotted with 20 transmitter vans with more than 300 microphones made available to the foreign press.

Joseph Goebbels had ensured that the Berlin Games would be broadcast to the world.

The excitement in the crowd was palpable especially about which of the teams due to march past in the opening ceremony would give the Nazi salute.

The Italian and Austrian teams did so enthusiastically, and the Bulgarians even adopted a Nazi-style goosestep but the crowd went wild for the French team who looking directly at the box where Hitler and the other Nazi leaders were sitting raised their right arms in salutation.

The French were later to somewhat unconvincingly deny that this was the Nazi salute but rather the Olympic one which was similar. The British and United States teams declined to give any form of salute.

The one thing the Nazi’s could not control however was what happened in competition and on the track.

On 3 August, with Hitler looking on, the black American athlete Jessie Owens won the 100 metres sprint, the highlight of any track and field event. The following day he won the long jump beating the great German champion Luz Long whom he was to later thank for providing him with invaluable advice.

On 5 August he won the 200 metres sprint.

Jesse Owens was single-handedly destroying the myth of Aryan racial superiority that the Nazi’s had been so eager to promote, and the rumour soon began to spread that Hitler, who had been personally congratulating the medal winners, had deliberately snubbed Owens.

The truth was more prosaic. Hitler had been selective in who he chose to greet from the start and had since been told that he must either congratulate all the winners or none at all. He chose the latter option.

What truly angered the Nazi leadership wasn’t Owens winning but the response of the predominantly German crowd in the stadium and elsewhere. He was cheered wherever he went, the crowd chanted his name whenever he entered the stadium, and people clamoured for his autograph.

On 9 August, under pressure from the German Government the American Olympic Team dropped two Jewish athletes Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller from their 4x100 metres relay team thereby providing Jesse Owens with the opportunity to win his fourth gold medal of the Games. He was the first man in Olympic history to do so.

But Owens aside, in almost every other respect the Berlin Olympics had been a triumph for the Nazi’s. It had been the best organised and most attended Games in the history of the event and was the first truly modern Olympiad.

The German Team had performed way above expectations finishing top of the medal table with 33 gold and medals 89 in total way ahead of the United States in second place. Yet despite all this all anyone was talking about was the supposedly racially inferior black athlete, Jesse Owens.

Hitler’s response to Jesse Owens was later documented by some of his colleagues.

Albert Speer, his favourite architect and later war-time Minister for Munitions wrote in his memoirs: “Each of the German victories, and there were a surprising number of these, made him happy, but he was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvellous coloured American runner Jesse Owens. People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug, their physiques were stronger than those of civilised whites and hence should be excluded from future Games.”

Baldur von Schirach, the leader of the Hitler Youth, recalled he said: “The Americans should be ashamed of themselves, letting Negroes win their medals for them.”

Jesse Owens declined the opportunity to criticise Adolf Hitler and the Nazi leadership He had, after all, been well received by the German people and highly praised by them for his achievements. He was instead to preserve his scorn for his treatment back home.

Following the Olympics Owens wanting to cash-in on his new-found fame declined to participate in events arranged for the American Olympic Team and returned to the United States. As a result, he was stripped of his amateur status effectively ending his career. Upon his return to America, he received few awards or accolades and was not invited as were many white athletes to meet with the President Franklin D Roosevelt and other leading officials while few of the lucrative job offers he had been promised materialised; so he took to the road to attend shows and take on all challengers including racing against horses to make ends meet and in later years was forced to take a series of menial jobs. It wasn’t until the late 1960’s that his achievements were at last acknowledged and he was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador for the United States. He died of lung cancer on 31 March 1980, aged 66.

Jesse Owens, along with Joe Louis who knocked out the German Max Schmeling on 6 June 1938, in the First Round of their World Heavyweight Title Fight, did more to destroy the myth peddled by the Nazi’s of Aryan racial superiority than any politician or any number of words written or spoken ever could.

When Leni Reifenstahl’s astonishing film Olympia was released on 20 April 1938, such had been the impact of Jesse Owens that despite her well-documented admiration for Hitler and pro-Nazi sympathies, his triumph was retained, and he was granted the same heroic status as any of the German athletes represented.

But within eighteen months of Olympia’s release any benefit the Nazi’s had expected to derive from it was lost in the chaos of war.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: