The Poor Laws

Posted on 9th October 2021

How to deal with the problem of the poor and the unemployed who are so often perceived to be a burden upon others is a constant dilemma. Society has sometimes tried to turn a blind eye to a poverty that is all too visible but for the most part it has felt an obligation to tackle an issue that impacts upon all. But its response however has often been cruel and harsh.

On 18 July 1349, King Edward III passed into law the Ordinance of Labourers which was primarily a response to the economic impact of the Black Death that had reduced England’s population by some 40%. The subsequent shortage of labour had seen wages rise and so the Ordinance intended to regulate the lives of an increasingly itinerate workforce and whilst it provided within it an element of poor relief its aim primarily was to drive labour costs down.

Regardless of previous attempts to control begging and sustain those who were incapable of doing so for themselves at a local level, a specific Poor Law did not become properly codified until Tudor times when a distinction was made between those who could not care for themselves and those deemed capable of work, the so-called “sturdy poor.”

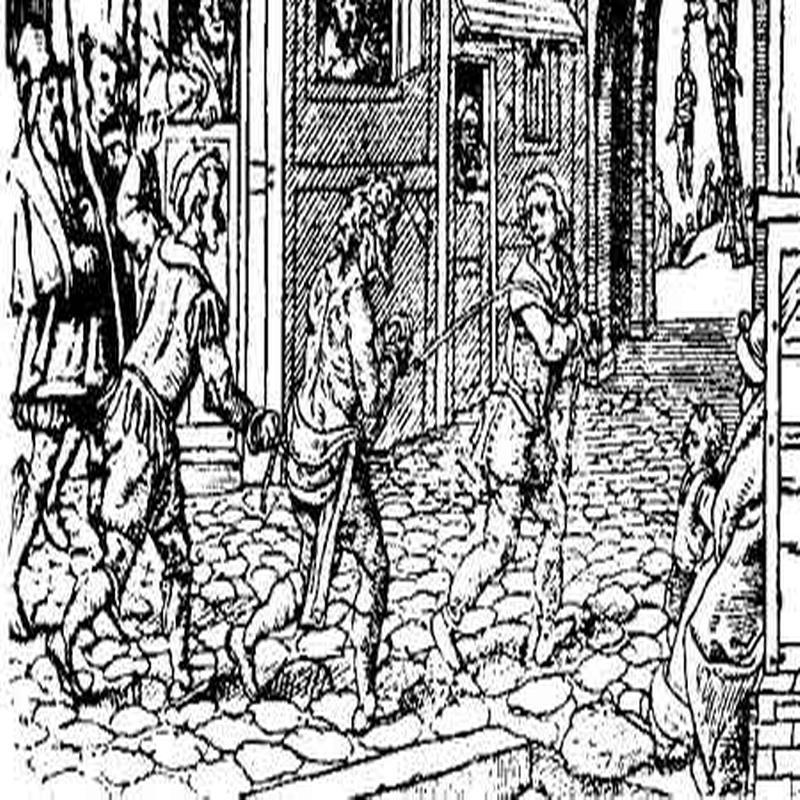

The homeless, vagrants, and the jobless were to be considered as one and the same. They were a burden upon the taxpayers of any parish and as such were to be punished. In 1495, King Henry VII passed a law the preamble of which read: “All such vagabonds, idle and suspected persons are then so taken and set in stocks, there to remain by space of three days, and three nights to have none other sustenance than bread and water, and there after the said three days, and three nights to be set large and commanded to avoid the town.”

Such harsh punishments, primarily aimed at the beggarly, did nothing to alleviate the problem of poverty itself, however.

The burden for poor relief had traditionally fallen upon the monasteries and the more charitable among the better off of any given parish. The monasteries had been abolished during the Reformation however, and no effort had been made to replace the charitable assistance they provided.

In 1530, King Henry VIII declared: “Idleness is the mother of all vices.” The Poor Relief he instituted provided the old, the sick, and the disabled with a licence to beg but those who continued to do so without a licence were to be treated no better than common criminals. In 1535, a statute was passed which allowed for vagrants to be arrested and whipped before being driven from the parish. If they continued to beg in the neighbouring parish then the same fate awaited them, and so on and so on.

During the reign of Henry’s son, Edward VI persistent offenders were to be branded on their forehead with a V for Vagrant, whipped, and publicly humiliated. The treatment of the poor was so harsh that many local Justices of the Peace were unwilling to implement the penalties laid down.

In 1572, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, boring through the ear was imposed on first time offenders whilst recidivist offenders were to be hanged. However, a series of poor harvests, rising inflation, and increased competition from abroad had seen England spiral into recession and unemployment had increased to the point where a properly codified and uniform system of poor relief had become essential.

The Elizabethan System of poor relief was introduced in 1601 and was paid for by levying local rates the burden of which fell predominantly upon local landowners who were often reluctant to pay.

Relief for those unable to work was provided in the form of food, the so-called Parish Loaf, and in clothing known as Outdoor Relief. It was also possible for the aged and infirm to be placed in Alms Houses though these were provided by charity and were not present in every parish; those who were considered able-bodied beggars, and as such deemed a threat to the good order of society, were often sent to Houses of Correction. Indeed, by 1607, there were to be Houses of Correction in every county.

There were around 15,000 parishes in England the boundaries of which were determined by the location of the parish Church. Each parish appointed an overseer for the poor who it was assumed would know those in his area who were deserving, and undeserving of Poor Relief, and it was likewise assumed that he would behave humanely towards them.

If you were from a neighbouring parish then you were not eligible for poor relief and would be forced to move after having received the requisite beating. Families within a parish that contained within them elderly or disabled relatives were obliged by law to take care of and provide for them.

The Elizabethan System of Poor Relief was to remain largely intact for 200 years and much like its forerunners it was not designed to alleviate poverty so much as to manage it and to punish those deemed indolent and responsible for their own pauperism.

Following a meeting of local Magistrates at the Pelican Inn in the Berkshire village of Speenhamland on 7 May 1795, an amendment was passed to the Elizabethan Poor Law. It was felt necessary because war with Revolutionary France had seen the price of grain reach levels well beyond the pockets of most people.

As a result, the Magistrates at Speenhamland devised a system of tested wage supplements based upon the price of bread and the number of children in a household. The responsibility for these top-up payments fell upon local landowners, many of whom were as always reluctant to contribute.

The Speenhamland System was soon heavily criticised for allowing able-bodied persons to draw upon the rates for the first time, as it also was for making no provision for punishments to be administered to those who were deliberately indolent, and it was felt by some to be the first step on the road to institutionalising pauperism and beggary.

These criticisms were pushed to one side on the grounds that it was an emergency measure designed to cope with the rigours of war, and upon the wars conclusion it was intended that the system would be abolished. But the war was to continue almost uninterrupted for the next twenty years and Napoleon Bonaparte’s eventual defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 only saw the problem of poverty and destitution increase as more than 200,000 now unemployed soldiers returned to British shores.

The increase in the number of paupers raised the amount of poor rate required and the local ratepayers whose resistance to poor relief was already well established increasingly demanded that the poor contribute themselves by doing unpaid work on their land or in their workshops. Others responded to the increased rate by reducing their own workers’ wages to make up the shortfall causing a great deal of resentment.

Other social pressures were being brought to bear – increased mechanisation and improved agricultural techniques saw the required number of farm labourers greatly reduced, land enclosures deprived people of their traditional grazing rights while the rapid advance of industrialisation saw many crafts destroyed and previously skilled workers reduced to penury. Meanwhile, the poor themselves also began to gravitate towards the wealthier parishes.

These would often be towns and trading centres and the sight of beggars on the street became increasingly commonplace so much so that parishes began to band together to raise the funds for the increased number of beggars. But the various systems in place for dealing with the problem of itinerant vagrancy, destitute families, abandoned children, and starvation was beginning to descend into chaos.

The Vagrancy Act of 1824, which sentenced those prosecuted for vagrancy to two weeks imprisonment and hard labour did little to alleviate the problem. Something had to be done.

The Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws was established in 1832.

The Commission was concerned that the Poor Laws extant were undermining prosperity and rewarding the poor for their indolence, idleness, and sloth. Their remit was not to find a solution to poverty but replace the Speenhamland system that subsidised earnings, the Roundsman system where Overseers would hire out cheap labour, and other ad hoc and localised methods of poor relief with a nationwide, regulated, and ultimately cheaper and less burdensome method of starvation prevention.

The Commission’s findings were to be greatly influenced by the work of the Reverend Thomas Malthus. His essay on the Principles of Population, first written in 1796, and subsequently updated over the next thirty years, expressed his view that population growth would always exponentially outstrip food supply and the means of subsistence.

Therefore, the poor, the burden of whose subsistence always fell upon others, should be discouraged from procreating. Discipline, he wrote, was required to turn them from their idle, wicked, and sinful ways. As a result, their poverty should remain unremittingly harsh.

The economist David Ricardo’s ‘Iron Law of Wages’ was also influential in holding that the aid given to the poor and unemployed suppressed the wages of those in work. Edwin Chadwick, who was the first Secretary of the Poor Law Commission, was a Utilitarian who believed that “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” could only be achieved by making the lives of the minority condemned to the Workhouse as miserable as possible.

The Workhouse was not then intended to be a place of salvation but one designed to deter the idle and the work shy, shake them out of their sloth, and force them to mend their ways. The premise underpinning the establishment of the Workhouse was that the conditions within it should be harsher than those confronting the poorest free labourer.

The Workhouse would be governed by the parish in which they resided and many of the regulations were set by its Overseer but there were standard rules that were to be applied nationally. Internees of the Workhouse were required to wear a uniform in order to signify their poverty and to distinguish them from others. Families would be split up with wives and husbands housed separately to prevent any further procreation. Children were also removed so that they did not pick up the bad habits of their parents. Workhouse internees were also expected to labour for their keep and this work could be as mundane as sewing sacks for women and rock-breaking for men.

Gambling, smoking, and the consumption of alcohol were forbidden and regular Church attendance compulsory while singing and whistling were banned and even talking was frowned upon. They were also forced to bathe under supervision.

The food comprised a kind of porridge or gruel served up three times a day and maintained at a subsistence level only.

Any infraction of the rules would be dealt with harshly with the inmates deprived of food, sentenced to time in the stocks or occasionally whipped though beatings were rare except in the case of children.

So harsh were the conditions in many Workhouses that some preferred to take their chances with starvation than enter one. For those with a family to feed, however, this was not an option. The stigma that was attached to any individual, or indeed family who had spent time in the Workhouse marked them out for opprobrium, often for the rest of their lives.

Despite its terrible reputation the Workhouse could also be beneficial to those willing to work hard and learn. It provided schooling and educational programmes – children were taught to read and write; women were provided with the skills required for employment in domestic service and men the knowledge and discipline for factory work or service in the military. Indeed, the Workhouse was to become the single most abundant source for domestic servants in the country.

Among those who took advantage of its educational programmes was the journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley and the comic-actor Charlie Chaplin.

The New Poor Law as it was known was to remain in place until the Liberal Chancellor David Lloyd George’s welfare reforms of 1906, which established a system of national insurance and provided for old age pensions. His reforms were the beginning of the Welfare State and following their implementation and the subsequent provision for unemployment benefit the need for a Workhouse in each parish became redundant and over the next thirty years they were to be gradually phased out.

Even so, as late as 1926 there were still 226,000 inmates in 600 Workhouses throughout the country, and the last Workhouse wasn’t closed until the Local Government Act of 1929.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: