The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe

Posted on 19th April 2021

The Witch-Hunt that scarred the European landscape for more than 200 years was a general but nonetheless clearly defined historical development. It has often been referred to as a craze which infers it was caused by some form of collective mental and social breakdown resulting in mass hysteria, but it was always more than that.

It began in earnest around 1420 and was provided with further impetus by the writings of Martin Luther and the onset of the Reformation a time of religious schism, political instability and war. Other factors would emerge overtime such as the early stirrings of capitalism and the rise of the Modern State with the Witch-Hunt acting as a precursor to the destruction of the old traditions that stood in the way of progress; but there was also the zeal of the clergy to eradicate all forms of paganism, the requirement to distract the masses from the causes of their own impoverishment and of course the widespread fear of women and the mysterious hold they had over men.

But the casting of spells for the purpose of magical healing had been commonplace since the dawn of time as had been the use of herbal remedies for every conceivable malady. Indeed, many monasteries would have substantial herb gardens that provided a cheap source of medicine for the poor of their parish.

The diagnosis of illness and the healing itself was often carried out by so-called ‘Wise Women’ also known as ‘Cunning Folk who could be found at the bedside of the sick or present at the birth of a child. But the distinction between this ‘White Magic’ and Maleficia or ‘Black Magic’ was often blurred.

The belief that bad magic was used to kill livestock, destroy crops and cause people harm was nothing new but it was theologians who were to create the crime of diabolism - that there existed a relationship between a witch and the devil. It made magic malicious and a spiritual crime and there was no longer good or bad magic but only witches who were by definition, heretics and apostates.

Magic, or witchcraft, was now attributed to an occult power which could be exercised in a variety of ways: a man could be harmed by the manipulation of his hair or by tampering with his sweat and excrement which contained his so-called vital spirits or by an invisible but potent emanation from the eyes known as ‘fascination’ or being ‘overlooked.’

Another means of harm was to damage something representing the victim – sticking pins in an image, burying an item of his clothing, writing his name on a scrap of paper and burning it. And of cause, there was imprecation where a witch would verbally abuse and pass malediction upon a person often within the hearing of others, a form of intimidation known as being ‘fore spoken.’ No one it seemed was any longer safe from a witch for the devil stalked the earth and they were his agents of misdeed and misfortune.

The primary agency for the criminalising of witchcraft was the Catholic Church which throughout the early decades of the fifteenth century, had collated a large and persuasive literature on the existence and practise of demonology. After all, did it not say in Deuteronomy: “Let there not be found among you anyone who immolates his son or daughter in the fire, nor a fortune-teller, soothsayer, charmer, diviner, or caster of spells, nor anyone who consults ghosts and spirits, or seeks oracles from the dead.” And again, in Exodus: “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.”

Pope Innocent VIII was convinced and in 1484 issued the Papal Bull Summis Desiderantes Affectibus (Desiring with Supreme Ardour) which effectively gave licence to Church and the Civil Authorities to actively pursue and prosecute those who practised magic in any form or for whatever purpose.

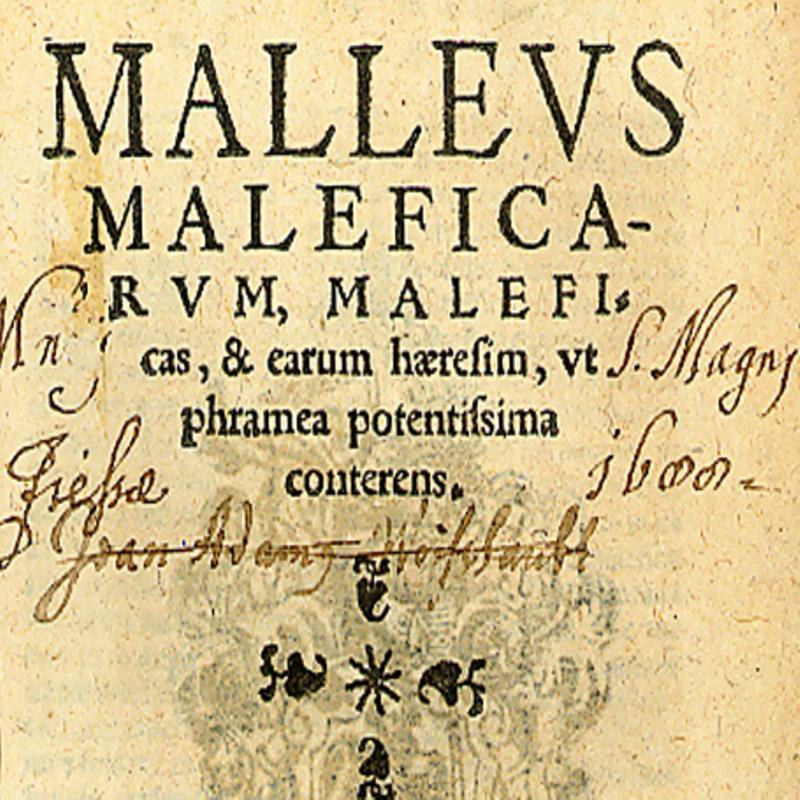

In 1486, two Dominican Monks Henry Kramer and Jacob Sprenger with the approval of the Pope published the Malleus Malificarum, or Hammer of the Witches, an effective guide on how to recognise and prosecute the devil’s disciples.

Magical powers were commonly associated with women, they administered the potions that cured ailments, there was the mystery of childbirth, and they exercised a sexual power that few men could resist. Indeed, it was said that a man should never marry in the month of May when a woman was thought to be at her most fertile for, he would forever be enfeebled and made prey to lust. Even a woman’s menstrual blood was considered toxic and harmful, a view as old as history itself with even Aristotle remarking that a mere glance from a menstruating woman could tarnish any mirror.

Kramer and Sprenger took these commonly held prejudices and formalised them in a text considered one of the most misogynistic in history. Women were feebler than men they wrote, both in mind and body, and that sexually insatiable and carnal by nature they were prey to the seduction of Satan just as their forebear Eve had been to temptation in the Garden of Eden. And that “Where there are many women there are many witches.”

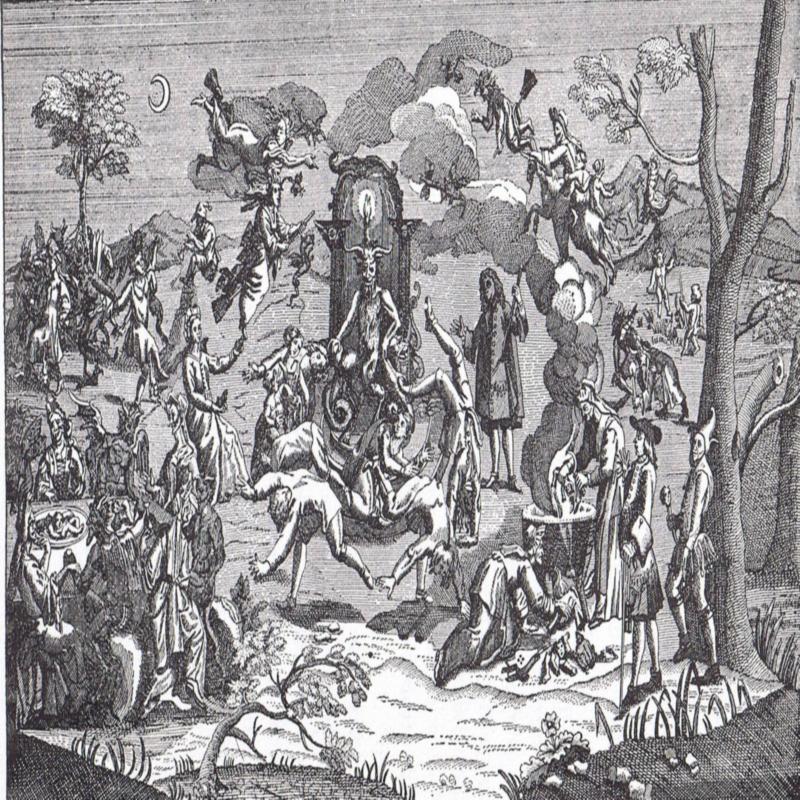

And the Church enthusiastically drew upon pornographic images of the Witches Sabbath with its gluttony, nudity, sexual perversity, mockery of the mass and desecration of the host as proof of their desire to have intercourse with the Devil. And they would bear the mark of their profession, a spot, wart or skin blemish that when pricked would not draw blood. A witch would also have as a companion the ‘Devil’s Familiar,’ a cat, or dog or some other pet.

The interrogation of a witch would involve them being stripped naked and made to walk backwards into the room to prevent them from casting a spell with their eyes as their accusers then inspected the body for evidence of the witch’s mark not that its absence indicated innocence merely that other means would be required to prove the accused persons guilt. Often still naked they would then be thrown into a prison cell where with no bed and deprived of food and water it was hoped the cold of the night alone would force a confession. If not, then the accused could be bound tight to induce pain or walked relentlessly around the cell to prevent sleep. If still no confession was forthcoming, then the penalty of ‘swimming’ could be imposed where the accused would be tied to a chair (known in England as Ducking Stools) and dipped beneath the waters of a pond or river. If they drowned, they were declared innocent but if they broke free and swam then they were seen to have rejected the purity of the baptism and were guilty.

The ordeal of those accused of witchcraft was relentless and without pity but the Malleus Maleficarum did at least signal a note of caution: “The accused shall as far as possible be given the benefit of the doubt.”

Differences existed between Catholic and Protestant understanding of the crime and the methodology adopted for its eradication.

The Catholic Church, the one true faith with the Pope the direct descendant of St Peter and therefore God’s representative on Earth, saw its responsibility as the elimination of heresy wherever it was found and in whatever form it took, and the subsequent chastisement of heretics and apostates would be public and ritualistic in its enactment – they must be seen to burn in the Fires of Hell. It was an elaborate exorcism of heresy for which the standard would be set by the Inquisition.

Protestantism with its greater emphasis on the individual in spiritual matters saw itself more as interlocutors on God’s behalf not the guardians of Christian purity or as the Lord’s High Executioner. In such circumstances a confession could lead to, if not exactly an acquittal, then the release of the accused into God’s hands. Even so, confession was rarely an option as it was firmly believed that to do so was to condemn oneself to eternal damnation.

The witch-hunt which barely relented in its ferocity for two centuries impacted upon all classes of society.

The Berwick Witch Trial in Scotland of 1590 was to witness the direct intervention of King James VI who was later to ruminate upon the subject of sorcery and diabolical malfeasance in his book Demonology.

Agnes Sampson, an elderly widow was accused of using sorcery to whip up the storm that had almost drowned the King and his new bride Anne on their return voyage from Denmark.

The always inquisitive James firm in his conviction that this was so and wanting to know why she would wish to harm him, and his innocent wife was both present at her interrogation and later her trial.

The unfortunate Agnes who denied the charges was garrotted to death and her body burned, just one of the more than 3,000 people executed for the crime of witchcraft in Scotland between 1560 and 1700.

Other notable witch trials were those that occurred in or near the town of Trier in Germany between 1581 and 1593 which took more than 1,000 lives. They were instigated by the Catholic Archbishop Johann von Schonenberg who had already rid his diocese of Protestants and Jews and now turned his ir upon those whose behaviour did not conform to his narrow vision of what a good Christian should be, and a charge of malfeasance was an easy one to make. Indeed, so thorough was the earnest Archbishop in his moral cleansing that it was to impinge upon every aspect of society regardless of class and station in life – nobles were accused, and wealthy merchants arrested but again it was women who bore the brunt of the persecution with some villages being left with no female presence whatsoever.

In fact, so institutionalised was the persecution of witches that it became an established career path for the ambitious and the means to a quick fortune for the unscrupulous.

An accusation of witchcraft which had long been the way to settle old scores now became a mechanism for legalised theft, a pattern that would be repeated as late as 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts.

As the Thirty Years War raged across the heartland of Europe and Germany in particular, was ravaged by famine and disease the people turned upon each other. Between 1626 and 1631 in the area around Wurzburg 900 people were burned at the stake. During the same period a further 600 were killed in the town of Bamberg but these are just the most prominent among many such incidents occurring not just in Germany but throughout Europe.

Events in Germany soon spread too much of northern France and nearby Scandinavia. At Torsaken in Sweden 70 people were executed for witchcraft 65 of them female whilst in the French region of Lorraine of the 2,000 people torched for supping with the devil between 1581 and 1591 82% were female with both figures reflective of the gender balance in such cases.

The largest witch trial in England occurred in 1612 in an area centred upon Pendle Hill in East Lancashire. It was as much the result of local Magistrates seeking favour by doing the King’s bidding as it was events at least in its scale and this despite the fact James had since expressed his doubts regarding the veracity of witchcraft.

The Pendle Witches were convicted largely on the evidence of the 9-year-old daughter of one of the accused even though the uncorroborated evidence of a child was impermissible under English law and is an example of how in offences pertaining to God, the devil, religion and heresy the law is often malleable. Of the ten witches hanged nine were women.

In England, unlike Europe, witchcraft was not deemed a heresy but a malicious act and as such those convicted of it were hanged and not burned at the stake. This remained the case despite widespread belief to the contrary and the work of theologians such as William Perkins who declared in 1608 that the Covenant with Satan was the very essence of witchcraft and that as such all witches should be executed without exception.

During the 1640’s, a period when the King and his Parliament were at war Mathew Hopkins the Witch-finder General was active in East Anglia and Essex. Declaring himself a lawyer licensed by Parliament to root out the devil from Godly Puritan England though there is little evidence for either, Hopkins was handsomely paid for his work often summoned by the village elite traumatised by the impact of war to eliminate supposed evil doers within their midst and he would always discover the witches they wanted him to helped by the knife with a retractable blade that drew no blood and caused no pain he used to confirm their guilt.

Between 1645 and 1647, he was responsible for at least 230 of the more than 400 executions for witchcraft committed during the Civil War.

Mathew Hopkins was to disappear from history as suddenly as he had emerged, but the Witch-finder General had made his mark.

The crime of witchcraft was codified into law first in France in 1490 but later also Denmark, Sweden, Russia, and many more besides. In England anti-witchcraft statutes were passed in 1542, 1563, 1604 and 1735. The last woman hanged for witchcraft in England was Alice Molland found guilty at Exeter Assizes in 1685 while the last person prosecuted was Jane Wenham at Hertford in 1712. *

Estimates for the number of those who were victims of the Witch-Hunt vary widely from around 40,000 to more than 250,000 but whereas official records point toward the more conservative figure these do not account for the many who, died as a result of local panics and mob violence.

There is no definitive answer as to why the Witch-Hunts that had burst with such violence and spread so quickly petered out as they did though relative peace after decades of the most terrible famine and war certainly played its part. In England the court transcripts told their own story – Juries simply ceased to convict.

*Postscript: That is if you ignore the bizarre case of Helen Duncan.

Duncan was a medium who in November 1941, announced during a séance that she had been visited by the spirit of a dead sailor who revealed to her that HMS Barham had been sunk with great loss of life. The loss of the Barham was a secret not revealed to the public for until many months after the tragedy so how she received news of its loss remains a mystery. It did however bring her to the attention of the Authorities who monitored her movements and attended her séances.

It seemed that she continued to reveal secrets for in January 1944, she was arrested but with investigations failing to unearth any evidence that she was in the pay of a foreign power or had any access to military intelligence she was charged under provisions in the 1735 Witch Act, or that she had used human conjuration to make deceased spirits appear in the present. She was jailed for nine months.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Women

Share this post: