Titanic II: Finding the Dead

Posted on 7th May 2021

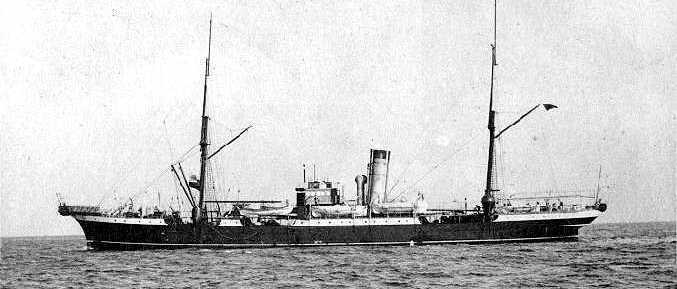

On 17 April 1912, the cable-laying ship Mackay-Bennett set sail from the port of Nova Scotia in Canada. It had been chartered at the cost of $500 a day by the White Star Line to recover the bodies, still floating in the freezing North Atlantic from the loss of the Ocean Liner Titanic two days earlier. It was a gruesome business and her crew were volunteers paid at double their usual rate.

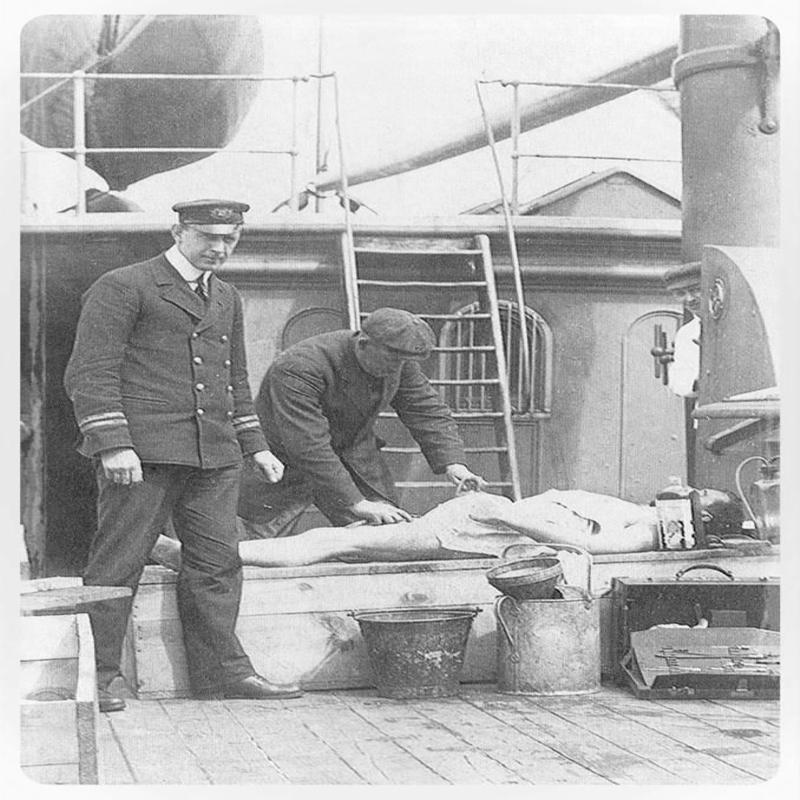

The ship carried 100 wooden coffins, an equal number of grey canvass bags, and tons of embalming fluid. Also on board was the Reverend Kenneth Hind and embalmers from Snow’s, the largest funeral emporium in Halifax.

Responding to messages received from the German Liner Bremen, whose passengers had reported seeing victims in the water, including a woman apparently clasping a baby and a small dog, the Mackay-Bennett made for the location of the sightings. They did so with some urgency following other reports that bodies had been hit by ships and spun into the air or mangled by their engines. It took two days for them to arrive at the scene but the weather with the sea choppy, and visibility poor they ship were unable to recover their first corpse until 20 April.

The sight that greeted the sailors was a disturbing one. Those victims who’d had life jackets were found floating together in small groups. Most of the victims of the Titanic had not drowned but died of hypothermia in the freezing waters, and in temperatures as low as -2 C survival time was predicted at only 15 to 20 minutes. Many of the bodies had been partially eaten and all were frozen and stiff.

The Mackay-Bennett’s Captain, Frederick Lardner, had orders to focus his recovery operation on passengers who could be identified by their clothing as being from First Class. The ships wooden coffins were to be used for First Class passengers only. The canvass bags were for any others with the bodies of Third-Class Passengers once identified if possible, recommitted to the deep – social hierarchy would be rigidly maintained even in death.

Captain Lardner, however, decided to return to the sea all those whose remains had deteriorated to such an extent they had become unrecognisable and could not be identified.

Within a short time, the Mackay-Bennett was crammed with a 190 bodies and other ships were called to join in the search. The SS Minia recovered a further 17 bodies, the SS Montmagny another three. The last victim to be pulled from the sea was James McGrady who had worked in the Titanic’s Saloon Bar and three months later the Liner Oceanic discovered the Titanic’s Collapsible A with three bodies on board.

Upon his return to Halifax Captain Lardner provided an account of his experience of which this is an extract:

“We reached the spot where I thought the Titanic had sunk just after the first watch began, and we shut down and let the ship drift with whatever current chose to carry her, on the theory that where the ship would be carried there we would find the bodies.

One pack of bodies we sighted at a distance looked like seagulls swimming on the water, the flapping in the breeze of the loose ends of their lifebelts making the resemblance to wings almost complete. When we bore down upon them the bodies looked like swimmers asleep. They were not floating but bolt upright, with heads up. The arms were outstretched, as if supporting the body. All faced one way – the way they were drifting.

We saw a big berg when we made this pack. It may have been the berg that sunk the liner. She was long and low-lying, rising perhaps 125 ft, or maybe 160 at her highest point which was well in from a bunch that sloped into the water. It was surrounded by wreckage and several bodies. The bodies were floating some near together, some far apart. There seemed no order among them – none were hand-in-hand or had embraced.

There were doors, chairs, and wood from the Titanic spread over thirty miles. We found a broken empty lifeboat upside down with a few bodies near it. It was a flat boat of the collapsible type. We found no sign of shooting on any of the bodies. We found several men in evening dress, but found no bodies lashed to doors. Those whom we found it necessary to bury were not men of prominence.

In my opinion the bulk of the bodies are in the ship. I think when she went down the water broke into her with great force and drove them into the hull.

I explain the reason that so many of the bodies picked up were members of the crew because they probably jumped before the ship took the fatal plunge. They were used to the ways of the sea and knew the danger of staying aboard her until the end. The passengers stayed with her and went down with her. They were crushed down in her as they sunk, and deep in her body they are finding their graves.

Those aboard her, the doctors think, were killed almost instantly by the terrible pressure in the vortex. Those who got away died later of freezing, I think few were drowned.”

A total of 337 bodies of the Titanic’s 1,517 victims were recovered from the sea. One of the first to be identified and collected for burial was that of the millionaire John Jacob Astor. He had on him a gold watch, gold cufflinks, a diamond ring, a gold pocketbook, and in his wallet he had 225 English pounds, 2,400 American dollars and 50 French francs. His money and precious jewels had done little to save him, but it had at least made his identification fairly straightforward.

Another body recovered was that of the Titanic’s Bandleader Wallace Hartley. He was found with his music case still strapped to his back. But for most of the other’s identification was far more difficult. Photographs of the dead were published in the hope that someone would recognise those that had been found with no identifying papers on them, but few were.

Today more than half of those bodies recovered from the sea following that terrible tragedy lie under numbered headstones in Halifax Cemetery, still unidentified.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: