Tolpuddle Martyrs

Posted on 19th February 2021

The fate of the Tolpuddle Martyrs has long formed a central plank of socialist propaganda, a cause celebre around which all factions of the Left no matter how moderate or extreme could unite in condemnation. It was the moment when the thin veneer of respectability was torn from those in authority who claimed to know best and do right in all good conscience. Instead, the mask slipped, and they revealed themselves to be the martinets of a cruel indifference concerned merely with the preservation of their own wealth and power.

There is more than an element of truth to this of course, but nothing occurs in a vacuum.

Decades of social upheaval and rural unrest had seen a deep mutual mistrust develop between factory owner and hand, tenant and landlord that was not easily overcome. The increased use of machine technology such as the Spinning Jenny, a multi-spindle frame with which one operator could do the work of eight men and the Threshing Machine which had a similar impact on the land had seen the workplace environment change irrevocably and the value of labour diminish. As a result, thousands were left without work or forced to do so for reduced wages.

Times then were harsh and made worse still by the imposition of the Corn Laws in 1815 which kept the price of bread artificially high, and the enclosure of the Common Land which deprived the labourers of an alternative means of subsistence. There was also no mechanism for the redress of their grievances other than to petition parliament and hope for a favourable response which despite the occasional voice raised in their defence such as that of Lord Byron below, were far and few between:

“I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return to the heart of a Christian country.”

The discordant voice of a charitable poet who rejected the well-rehearsed protocols of acceptable behaviour and had a penchant for bedding the wives of his fellow peers elicited little sympathy and carried even less weight, and so it was with other Radicals tainted by the stigma of extremism who likewise aired their concerns - the poverty and the starvation would continue.

Where goodwill was absent loathing filled the void, where reason had failed intimidation became the preferred weapon of both sides. The landowners would use the full force of the law, the workers threats of violence with those they considered most responsible for their plight specifically targeted for retribution: Sir, your name is down amongst the black hearts in the black book, and this is to advise you and the likes of you, the Parson and the Justice, to make your wills. You have been the Blackguard Enemies of the People on all occasions. You have not done as you ought.

A refusal to meet with a delegation of workers one day could result in the destruction of the landowners’ property the next. An attack on your home or even upon your person might follow and the countryside at night became a fearful place with those isolated homes vulnerable to robbery and arson often plunged into darkness as candles were snuffed out at the first sound of the unexpected on the still air or the glimmer of an unsolicited light in the distance.

The towns were barely any safer with large gatherings often turning violent and even when the worst of the disturbances appeared over communities remained divided and the atmosphere tense.

The governing class, the nobility and landowners, did not take kindly to threats and there was no desire on their part to reach an accommodation - they would meet force with force. Their suppression of the Luddites had been brutal, and the Magistrates would be kept no less busy when confronting the Captain Swing Riots twenty years later.

During the years of rural unrest over a thousand men, women, and children had been imprisoned or transported to Australia, and 19 had been hanged. More still had lost both their livelihoods and their homes. It was in this atmosphere of fear and mistrust that events in the village of Tolpuddle would unravel.

Tolpuddle is a small village barely distinguishable from those others around it somnolent among the rolling hills, green pastures, and lush meadows of the Dorsetshire countryside, but the beauty of the surroundings belied the squalor in which most lived; dilapidated cottages with broken roofs, shutters for windows and little insulation against the harsh winter climate were commonplace.

Farming provided the only means of subsistence for most and working the land was hard, the soil difficult to till and plant and the days long with often twelve hours or more in the summer spent at the plough or at work with the scythe. Yet for this they were paid little, and the landowners sought to pay them even less.

In the autumn of 1831, at the height of the disturbances in Dorset a 37-year-old ploughman and Methodist lay preacher George Loveless, formed part of a delegation of agricultural labourers from Tolpuddle and elsewhere who having seen their wages reduced from 12 to 9 shillings a week met with employers to demand it rise to 10 shillings a week in line with that in neighbouring counties.

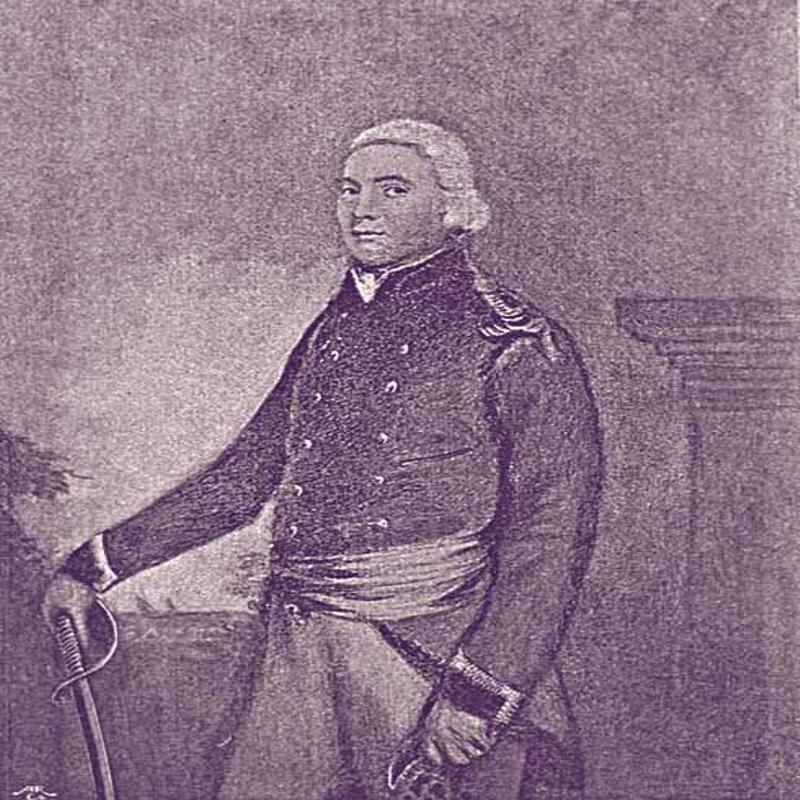

The man who presided over the meeting was James Frampton, a local landowner, magistrate, and former commander of the Dorset Yeomanry not known to be sympathetic towards the labourers and so it proved. In no uncertain terms he told them:

“There is no law which compels masters to give anything extra to their servants. You must work for whatever your employers think fit to give you.”

Rather than a pay rise over the coming months and years the farm labourers of Tolpuddle would experience further reductions in their income down to as little as 7 shillings a week. It was difficult enough for anyone to survive on such meagre scraps, but it was to prove an intolerable burden for those with families to support.

With 20 shillings to a pound and the shilling itself divided into 12 pennies (or 24 half-pennies) what follows is a list of staple household items of the time and their cost. It is worth bearing in mind that George Loveless for example, had a wife, Betsy, and three children to provide for:

Rent 1/2d, Potatoes 1s, Coal 9d, Salt 5d, Butter 5d, Cheese 3d, Soap 3d, Candles 3d, Tea 3d, Thread 3d. A loaf of bread, that staple of most diets would often cost more than the farm worker made in a week while meat was only available if bought from a local poacher which was itself a criminal offence.

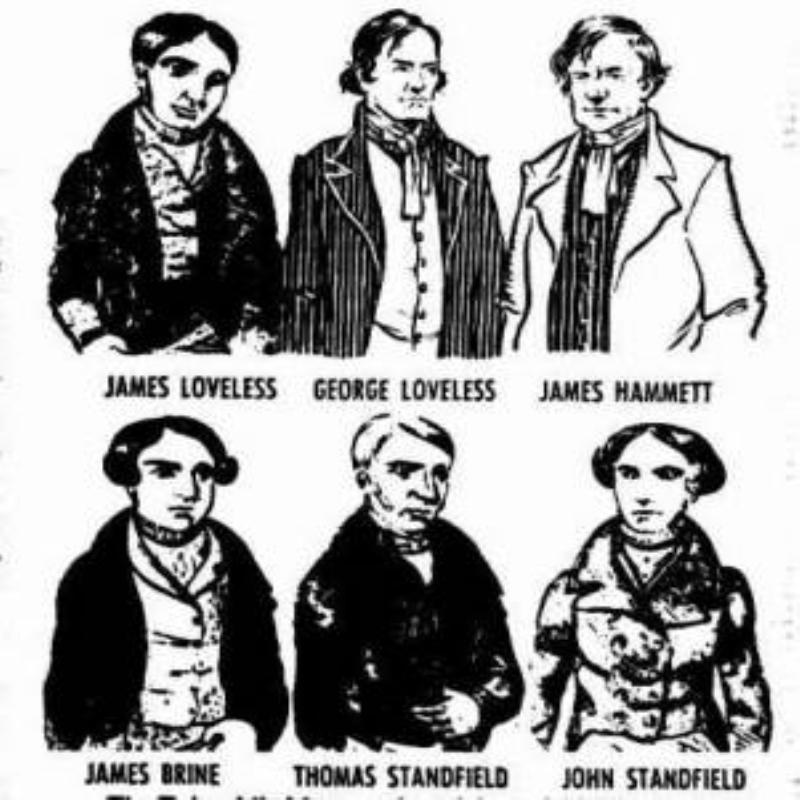

The six men who would soon become the notorious Tolpuddle Martyrs were for the most part related to one another or close friends. They were:

George Loveless mentioned previously was a self-taught man well known to the local magistrates and treated with suspicion.

James Loveless, the younger brother of George, and also a Methodist lay preacher, he had already been singled out as a troublemaker following riots in the nearby village of Piddleton.

Thomas Standfield, aged 42 who was married to the Loveless’s sister, Diana.

John Standfield, his son

James Brine, who at just 20 years of age was the youngest of the group and the close friend of John Standfield.

James Hammett was the outsider of the group neither a Methodist nor a close friend he was a convicted felon who had seen the inside of a prison cell more often than he had a church.

Rumours were circulating that the local employers intended to reduce the wages of agricultural labourers even further to just 6s a week. This caused no little despair and an anger that George Loveless was eager to exploit. Meeting regularly beneath the Sycamore Tree in the centre of the village the workers shared their woes and pondered what to do about them. Loveless knew what to do and told them so - they needed to organise. Trade Unions had been de facto legal ever since the repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824 since when there a proliferation of so-called Friendly Societies had been. Looking to form just such a society George Loveless contacted the socialist factory owner Robert Owen who was seeking to bring all the Friendly Societies under the umbrella of his Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (GNCTU) for how to do so. He had committed no crime by his actions, and he was encouraged to proceed but was also warned of the possible consequences of doing so.

Trade Unions may have been permitted but they weren’t welcome and those who were members of or sought to form one would be threatened, spied upon and ostracised from their local community. As Methodists most of the Martyrs were used to being thought outsiders. The Church of England might be mocked as the Tory Party at prayer, but it was still central to the life of every village community and dissenters such as the Methodists who did not attend Anglican Church Service were thought suspect and unreliable. With its Biblical mantra, “in all labour there is profit but the talk of the lips leadeth only to penury,” the Established Church may have been in the pocket of the ruling class but the order, deference, and obedience it preached was widely accepted even if the labour was hard, the profit slight, and the penury great.

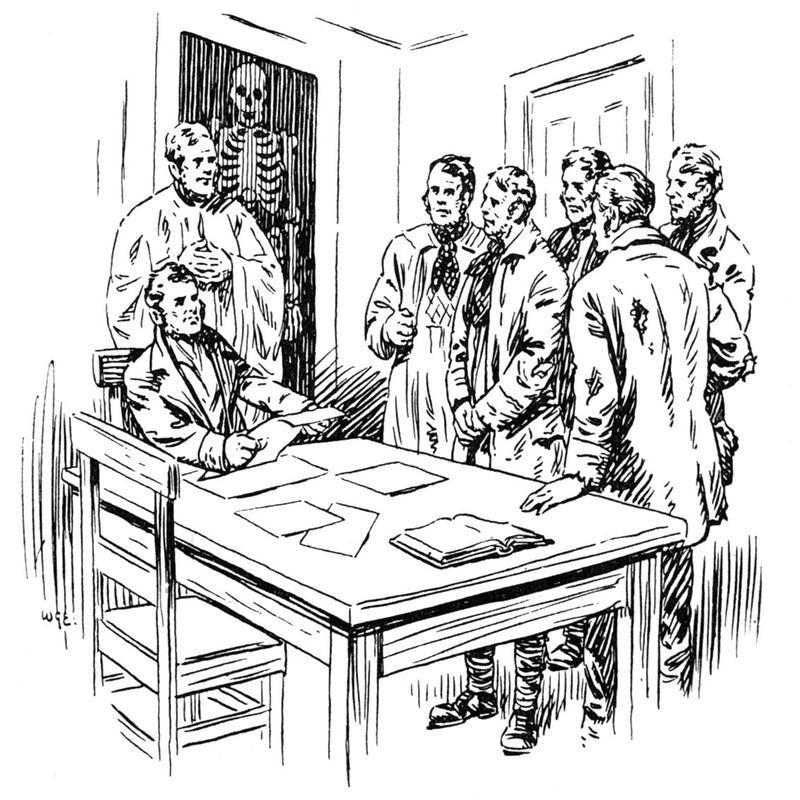

In October 1834, George Loveless and the other five men who met regularly and in public beneath that old Sycamore Tree formed the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. It would be 1 shilling to join and 1 penny a week subscription thereafter and the men would meet in the upper room of John Standfield’s cottage where an initiation ceremony would take place and an oath of allegiance sworn.

On 9 December just such a ceremony occurred where all present agreed to abide by the societies rules and to keep its secrets. Then kneeling before a copy of the Bible and the picture of a skeleton they swore the oath.

One of those in attendance that night was a labourer named Edward Legg who whether he was already a paid spy or was simply looking to make a little money reported events to Squire Frampton and agreed to provide testimony to any preliminary court proceedings that might occur. Squire Frampton wasn’t one to turn a blind eye to such events and swearing an oath of allegiance to anyone other than the Monarch had been illegal ever since the passage of the Illegal Oaths Act that followed in the wake of the Nore and Spithead Naval Mutinies of 1797.

Yet the swearing of oaths was hardly uncommon whether it be to join a guild, a literary society or even the Freemasons. Regardless, armed with evidence of illegal activity Squire Frampton now wrote to his old friend the Home Secretary Lord Melbourne:

“Sir, it is with extreme regret that I feel myself obliged to communicate to your Lordship so unfavourable a report on the state of the agricultural population of this part of Dorsetshire but our earnest desire for the welfare of these labourers whose manners have undergone a significant change and who becoming remarkably restless and unsettled since unions have been established begs us most anxious that some measures should be adopted that will restore their good sense and order.”

Lord Melbourne urged caution he had no desire to stir up trouble where none existed, but Squire Frampton was insistent telling him, “Dangerous and alarming combinations are being entered into to which they are bound by oaths administered in secret.” His Lordship did not require much persuading and would not stand in his friend’s way should he choose to pursue the miscreants.

On the morning of 24 February 1834, George Loveless was served with a warrant for his arrest and taken into custody. The other five members of the Tolpuddle Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers were likewise arrested – their crime, the administering and swearing of an illegal oath.

Any prospect of a fair trial appeared slight, Squire Frampton sat on the jury while its chairman John Ponsonby the local M.P and brother-in-law of Lord Melbourne had it seemed already made up his mind: “A conviction is essential the working class have attached great importance to this trial. The sentence passed must serve as a warning to others then we will put an end to his growing restlessness which is exceedingly disgusting.”

The Judge presiding Baron Williams agreed: “The object of all legal punishment is not altogether with the view of operating on the offenders themselves. It is also for the sake of offering an example and a warning.”

Regardless of the animus evident in the preliminary hearings the trial itself was conducted with all due respect to the law. The Defence argued that the Oath administered, if that is what it was, could not be judged illegal as in forming a Union the defendants were not engaged in an illegal pursuit. Also, the Act under which they were charged was specific to mutiny and seditious activity within the Armed Forces. Judge Williams thought otherwise and surmising it had a wider application declared that if the jury found an oath had been taken then it was an illegal oath and that therefore a crime had been committed. This remains a matter of conjecture and the jury in passing a guilty verdict could perhaps be exonerated of bias but the sentence then passed is much more difficult to justify. Though there had been no withdrawal of labour, no threats made, or acts of violence committed the men were given seven years hard labour in the Australian Colonies. With little possibility of being able to return it was in effect a life sentence – a moving statement delivered by George Loveless from the dock did little to alleviate the pain.

The sentence passed was clearly disproportionate to the crime committed, if any crime had been committed at all, and it was widely assumed that Lord Melbourne would commute it. When he did not but instead proceeded to confirm it the outrage was manifest even among the reliably partisan press:

“This sentence seems to us too severe, but it may be useful if it spreads alarm among those powerful disturbers of the town populations who combine in spite of high wages and whose combinations are so destructive.” (The Times)

“Trade Unions are bad things; they are bad in principle and lead to bad consequences but let those who have sinned in ignorance have the benefit of that ignorance. Let the six poor Dorsetshire fellows be restored to their cottages.” (Morning Herald)

“The whole nation has been surprised at the sentence, not one man in the whole community appearing to know there was any law to punish men for taking oaths.” (Cobbett’s Register)

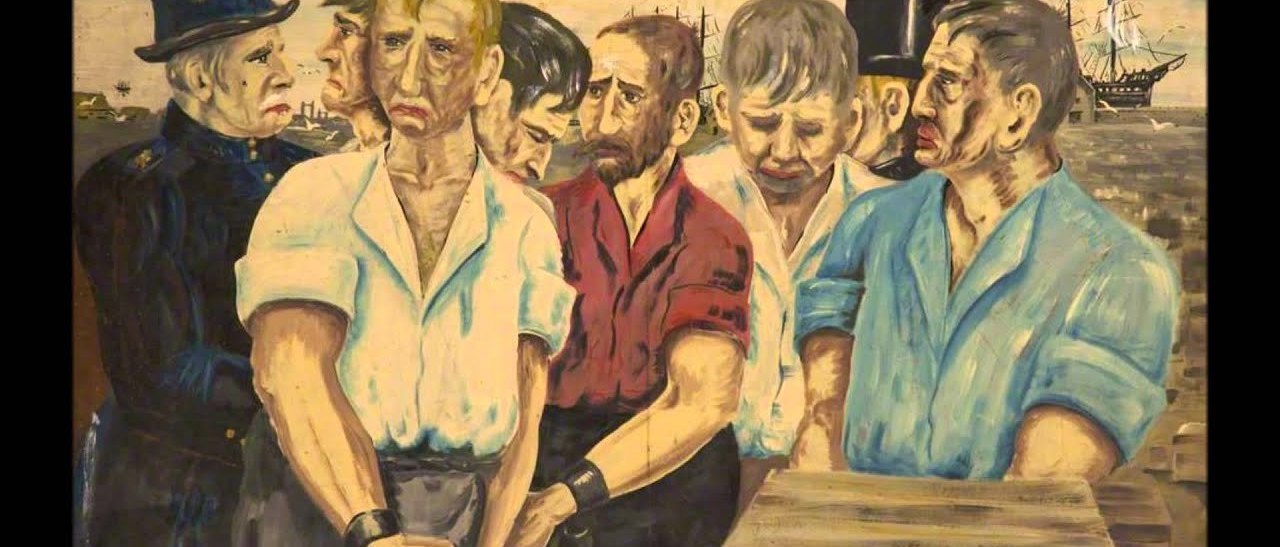

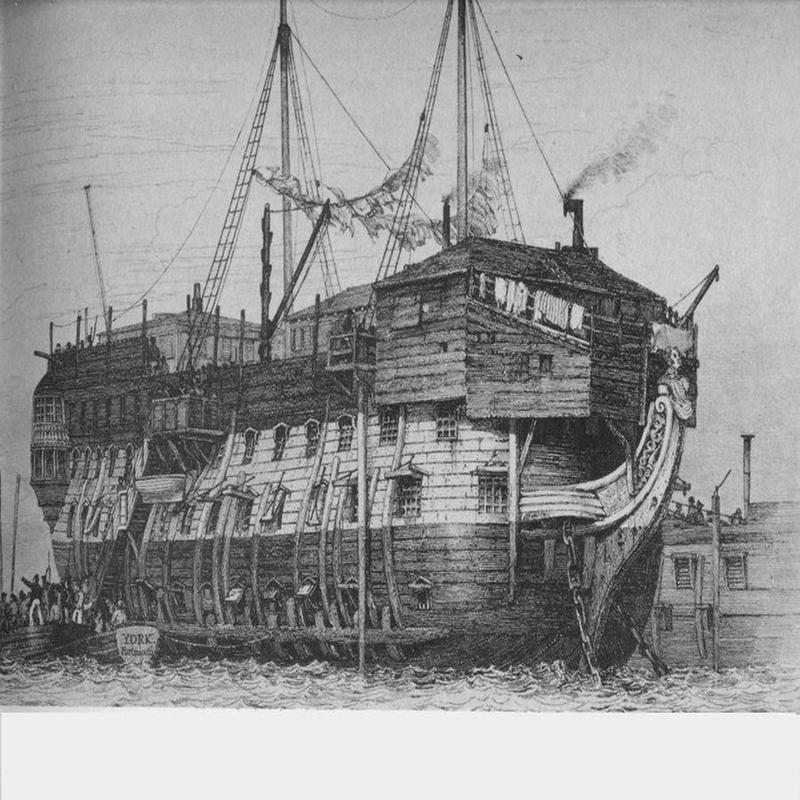

Upon sentencing five of the six men were taken from the cells beneath Dorchester Assizes in chains to the prison hulks York and Leviathan moored in Portsmouth Harbour. Condemned ships of multiple decks overcrowded and damp where prisoner’s awaited transportation to the colonies. The squalor and the misery of the prison hulks were a grim portent of what was to come. George Loveless, who was too sick to be moved, would join them later.

Taken deep into the hold of the ship the hatches overhead were shut tight and locked and the prisoners were manacled and chained to their bunks for the entirety of a voyage that could take up to six months. Sea sickness was ever present and disease rife particularly cholera and dysentery and some already weakened by time spent aboard the Prison Hulks would not survive the journey. By the time of the Martyrs transportation the payment of bonuses and rewards for the safe delivery of prisoners had improved conditions somewhat while the surgeons were more diligent and the food adequate if uninspiring. On occasion they might be permitted on deck for fresh air and exercise but that remained at the discretion of the ship’s Captain.

Even aboard those ships that adopted a more tolerant regime the gloom, stench, damp, heat, and sheer boredom made conditions intolerable, and conditions barely improved upon their arrival where sent to camps they were put to work for up to twelve hours a day in the most appalling and unimaginable heat barefoot and in threadbare clothes, cut, bruised, sunburnt and with heatstroke a constant threat. Poorly fed and frequently dehydrated they received little sympathy from their overseers who saw them not just as indentured slaves to be worked but criminals to be punished as the law required.

James Brine, who like all Tolpuddle Martyrs apart from James Hammett left a detailed account of their experiences, described how he had to walk miles every day to dig post holes for hours on end and was made to spend seventeen consecutive days up to his waist in water washing sheep. Having earlier been robbed and stripped of the few possessions he had by Aborigines he was forced to sleep at night on the hard ground without so much as a blanket to cover him. When he requested one, he was told he had been provided for and would receive no further help - he was there to be punished, after all.

It was a servitude for which it seemed they would never be redeemed, and they could have had no knowledge of the campaign already underway in their homeland to secure their return.

The fledgling trade union movement had been quick to act displaying an ability to organise that surprised many. Under the guidance of Robert Owen’s GNCTU and supported by several radical MPs among the most prominent of whom were William Cobbett, Joseph Hume and Thomas Wakeley who maintained the pressure in Parliament they campaigned relentlessly on the men’s behalf.

On 24 March 1834 a rally was held in London which addressed by Robert Owen attracted 10,000 people. Soon after Owen along with other leading trade unionists and social reformers formed the London Dorchester Committee to raise funds to fight the legal case and secure the men’s return. Their most immediate concern however, would be the welfare of the Martyr’s families.

Having no income with which to support themselves and their children the women had little option but to apply for poor relief but it was Squire Frampton who was responsible for its distribution and he did not look kindly upon them. Holding them to blame for their own distress he refused any help whatsoever, stating bluntly that if they could afford to pay the union dues then they could afford to feed themselves. They begged him to reconsider but he would not, and so when no help from church or charity materialised they wrote with some urgency to the London Dorchester Committee: “Tolpuddle has for many years been noticed for its tyranny and oppression and cruelty and now the union is broke up here. They mean us to suffer for the offences of our husbands.” The Dorchester Committee responded with haste supporting the families from funds raised. They responded with a collective letter of thanks: “Sir, on Tuesday last a gentleman came from London and relieved us £2.3s each, all equal alike, had it not been for this I cannot tell you what we should have done.”

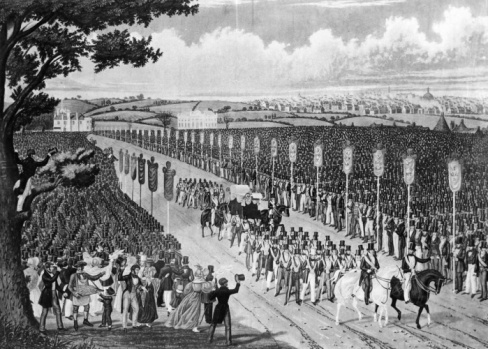

On 21 April, a grand procession threaded its way through the streets of London to Copenhagen Fields where more than 100,000 people carrying placards and unfurling trade union banners rallied in open defiance of a government that had ordered the army be present and for thousands of Special Constables to line the route. It was a show of strength and a tense stand-off ensued while the latest petition, one of sixteen in total which Lord Melbourne had refused to accept in person was delivered to Parliament.

The future mentor to the young Queen Victoria knew full well that the sentence passed upon the men from Tolpuddle could not be justified but he had tacitly approved the actions of the Dorchester Magistrates and was not inclined towards a mea culpa – as long as he remained in Office the protests would fall on deaf ears.

However, called upon by the King to form a minority Whig Administration by July 1834 Lord Melbourne had stood down as Home Secretary to become Prime Minister. The task of keeping unified an increasingly fractious Whig Party was difficult enough and he was glad to wash his hands of the Tolpuddle nonsense. His replacement at the Home Office was John William Ponsonby, Lord Duncannon, who as we have already seen was no friend to those he deemed outside the law.

By November however, he too had gone to be replaced by Lord John Russell, a more sympathetic character who was unwilling to take ownership of his predecessor’s mistakes. In June 1835, he bowed to pressure and pardoned the six men but there were conditions attached one of which insisted that the convictions remain in place. The men who continued to maintain their innocence refused to accept any pardon that did not exonerate them of all wrongdoing.

It was a fight Russell was unwilling to engage in despite being counselled that bowing to the mob set a dangerous precedent. So, on 14 March 1836, King William IV acting on the recommendation of the Home Secretary granted the Tolpuddle Martyrs as they had since become known, a full and absolute pardon – they could return home as free men.

It is easy to paint Squire Frampton as the villain of the peace, and indeed he was, but it was never as straightforward as mere contempt for his social inferiors. He believed in the old verse, “the rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate. He made them high and lowly, He ordered their estate,” But with that belief came a responsibility, to maintain order and secure the status quo that benefited all and made England a country governed according to the rule of law and the home of free men. It was a responsibility he took seriously, and having witnessed from afar the chaos and bloodshed of the French Revolution and the lack of respect shown for private property which had been such a central feature of Luddism he was determined that no such thing should ever occur in that small part of the English countryside which fell under his jurisdiction. Even so, no one was hanged during the Captain Swing riots while he was a Magistrate. Neither was he negligent of the needs of ordinary people building a schoolhouse for the village children and paying for the repair of workers cottages out of his own pocket, but such largesse came at a price - deference to the social order and obedience to the law of the land.

The campaign for the release and return of the Tolpuddle Martyrs had proven a resounding success and the first to arrive back in England on 13 June 1837 was George Loveless who was soon putting pen to paper to give his account of events. The others returned over the coming months but to surprisingly little fanfare given their role in the cause that had dominated the public discourse for so long. Events had moved on and Chartism, the campaign for an extension of the franchise and greater working class representation in Parliament, had trumped trade union rights as the burning issue of the day. Robert Owen’s GNCTU had already collapsed and it might be said a little intimidation goes a long way for many unions now drew up the drawbridge, ceased to work with others, kept their secrets and secured their finances.

The Martyrs weren’t expected to return to Tolpuddle and the London Dorchester Committee had used the funds raised to purchase the lease on a number of farms in Essex for their use. Only James Hammett among them refused any help and instead did return home and resume work as an agricultural labourer. The others soon showed themselves not to be the innocents so often portrayed but committed radicals and trade union activists who not long after arriving in the village of Greensted established a branch of the Chartist Association. It did not make them popular in their new homes. The Essex Standard wrote of George Loveless: “Instead of quietly fulfilling the duties of his station he is still dabbling in the dirty waters of radicalism and publishing pamphlets to keep up the old game.”

Preached against by the Church and ostracised by their local community once more, it soon became clear that the Martyrs would never be free of suspicion or indeed pressure from their friends to keep up the good fight. They also struggled make a success of running their own farms in a hostile and unsupportive environment. So over the next few years with the help of benefactors they all, with the exception of James Hammett, made a new life for themselves in Ontario, Canada, where they remained what they had always been, a close knit community of friends.

It falls to few Martyrs to live long and prosper but for the most part those from Tolpuddle did:

George Loveless, farmed his own land and became a respected Minister and Church Elder. He died in 1874, aged 77.

James Loveless, as he had most his life followed in his older brother’s footsteps becoming both a farmer and a Sexton in the Methodist Church. He died in 1873, aged 65.

Thomas Standfield also purchased land with the money provided to him. He died in 1864, aged 74.

John Standfield, ran a hotel, was elected Mayor, and later become a Justice of the Peace. He died in 1896, aged 83.

James Brine married Thomas Standfield’s daughter Elizabeth with whom he sired 11 children. In between times he was a successful businessman. He died in 1902, aged 90.

James Hammett, who as we have seen returned to Tolpuddle found gainful employment for a time as a building labourer but often fell into penury. In old age he committed himself to the Dorchester Workhouse to avoid becoming a burden to his family. He died in 1891, aged 80.

The events at Tolpuddle are now commemorated in the third week of July with a rally and festival in the village attended by leading trade unionists, representatives of the Labour Party and other non-affiliated left-wing groups.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: