Trial and Execution of Charles I

Posted on 15th January 2021

On 14 July 1645, on the fog-bound hills outside the small town of Naseby in Northamptonshire the heavily outnumbered army of King Charles I was routed by the forces of Parliament. It was to prove the turning point in a brutal and bloody civil war that had already cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. In the ensuing months those towns and cities that remained loyal to the King surrendered and his armies still in the field were defeated and dispersed. By the turn of the year, he was besieged in his capital Oxford with no hope of relief but still he remained unwilling to surrender himself to an enemy he thought traitors, men he could not trust with his life.

On the night of 29 April 1646, he had his hair cut short and his beard trimmed before fleeing Oxford disguised as a commoner in the company of just his Chaplain Michael Hudson and personal attendant, Sir John Ashburnham. He was hoping to take ship to the Continent but with the ports closely monitored he was unable to do so. Afraid of falling into the wrong hands and with nowhere else to go he gave himself up to the Scottish Army based at Newark.

He thought he could get a better deal from the Scots than he would from his own Parliament but following some fruitless negotiations the Scots sold him on to the English for £400,000, prompting Charles to remark bitterly that he had been - bartered away rather cheaply.

In custody in England, Charles made much of a willingness on his part to reconcile with those he had so recently been at war while at the same time playing one side off against the other. He knew that Parliament was divided between moderates and extremists both religious and republican. Many wanted nothing more than a return to a stable monarchy and were willing to see him once more upon the throne, but this would be as a monarch subject to parliament. This Charles could not be however, his Kingship was a grant from God, and he ruled by Divine Right. He was by nature and nurture incapable of being a Constitutional Monarch, but he was nonetheless determined to take advantage of the situation.

While Parliament continued its long, drawn out negotiations with the King, the Officers and men of the New Model Army grew increasingly frustrated. Indeed, under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton they decided to circumvent parliament by negotiating with the King themselves. This Charles was happy to do as he was playing the long game and looking less towards an agreement than he was to renewing hostilities.

In November, 1647, Charles escaped captivity and fled to the Isle of Wight where he believed the Governor, Robert Hammond, would be more sympathetic to his cause. He was not, yet though he was imprisoned once more his near escape only added to the urgency of agreeing a negotiated settlement. Charles however, continued to deflect the overtures made by both Cromwell and Parliament. His objectives lay elsewhere, namely in secret negotiations with his old nemesis, the Scots.

On 26 December 1647, while still in captivity at Carisbrooke Castle he signed a Treaty with the Scots known as the "The Engagement" by which he agreed to the establishment of Presbyterianism in England for an initial period of three years for which the Scottish Army would invade England in support of Royalist uprisings throughout the country and restore Charles to his throne. In the meantime, the King's agents would stir up unrest in those areas of the country still believed to be loyal to his person. But there was no real yearning among the people for a renewal of hostilities and when the uprisings began in July 1648, they were easily suppressed. The Scots held to their side of the bargain however, and invaded England with an army 20,000 strong but were cornered and routed at Preston by Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army.

Charles I’s last chance of a Restoration under the old terms of his Kingship had been lost but little did he realise that his attempt to initiate a Second Civil War had also all but sealed his own fate and would ultimately cost him his life.

Oliver Cromwell had been one of those within the divided New Model Army in favour of a negotiated settlement with the King but now he now changed his mind believing his alliance with the Scots: "A more prodigious treason than any that had been perfected before; because the former quarrel was that Englishmen might rule over one another, this to vassalise us to another nation."

What infuriated him even more was the refusal of the King to accept the Judgement of God passed down at the Battle of Marston Moor, Naseby, and elsewhere. There could be no doubt that all the ills that had beset the country, all the blood-shed and all the treasure lost could be firmly laid at the feet of Charles Stuart.

He now believed it was God’s Will to settle with this King, this Man of Blood who said one thing and did another, who could not be trusted to keep his word, and that there would be no peace as long as he lived.

Despite Charles’s attempt to renew hostilities the long and painful negotiations between the emissaries of Parliament and the King’s person continued until at last it appeared as if a compromise may have been reached. On 1 December 1648, the Long Parliament which had sat in continual session since the beginning of the Civil War accepted the King's terms for his restoration to power by a vote of 129 to 83. Almost immediately the army voiced their objections and made it clear that they would not accept the outcome of the vote.

By now the most powerful man in the country Oliver Cromwell ordered the suspension of all Parliamentary proceedings and the arrest of 41 of those MP's who had voted in favour of a Restoration. Instead of being restored to his throne King Charles I would now stand trial for his life charged with treason.

Parliament which saw itself as ill-served had no intention of doing the army’s bidding and certainly not on the say so of its spokesman ‘Squire Cromwell’ forcing him to act.

On 6 December, Colonel Thomas Pride surrounded the Chamber of the House of Commons with troops. As the MP's entered he checked their names against a list of those marked unreliable. He was, perhaps, a little over-zealous in his work for by the time he had finished only 71 of 489 MP's remained and 189 of those barred entry had also been arrested and imprisoned.

With ‘Pride’s Purge’ the Long Parliament which had sat for eight years was effectively dissolved. What remained became known as "the Rump" and it was to be a tool in the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the New Model Army.

Cromwell, who had been campaigning in the north, returned to London the following day and publicly endorsed Pride's Purge. He was determined "to cut the King's head off with the Crown on it" and now he had the means to do so. On 4 January 1649, an Ordinance was placed before the Rump demanding that the King be tried for treason. Only 46 of the remaining 71 MPs turned up to vote and of these only 26 voted in favour, but it was enough. The following day the House of Lords overwhelmingly rejected the same proposal, but this was ignored.

There was no precedent for putting a reigning Monarch on trial and no mechanism for doing so. As a result, the High Court of Justice, a special ad hoc Tribunal was created. The Tribunal was to be made up of 135 hand-picked members, though most of the most prominent men chosen, declined the invitation and only 68 of the so-called second-string ever turned up to witness the trial of the man they were to pass judgement on, which led Charles to mockingly declare that - he did recognise but eight of them.

The prosecution was to be led by the Solicitor-General Sir John Cook, but Cromwell was unable to find anyone from among the Tribunal willing to serve as Chief Justice, so the role went to an ambitious but obscure lawyer from Northumberland, John Bradshaw.

But Cromwell was determined that this would no sham trial, no grubby backroom assassination. The proceedings of the Trial should be made as public as possible so that the people could witness for themselves the guilt of this King who had refused to accept the outcome of a war that he had started, his unquenchable desire for further bloodshed, and the Judgement that God had passed upon him. Charles reacted impassively upon being informed that he was to stand trial for his life and read the indictment with seeming indifference:

"For accomplishment of such his designs and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented . . . that the wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and the upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation."

Despite the sound and the fury of the religious zealots and republican extremists baying for the blood of the King, Cromwell was aware that there was little appetite among the common people for vengeance, or justice as he would have seen it. So, the trial would not be a long drawn out affair, the rush to judgement would be swift and unhindered by equivocation.

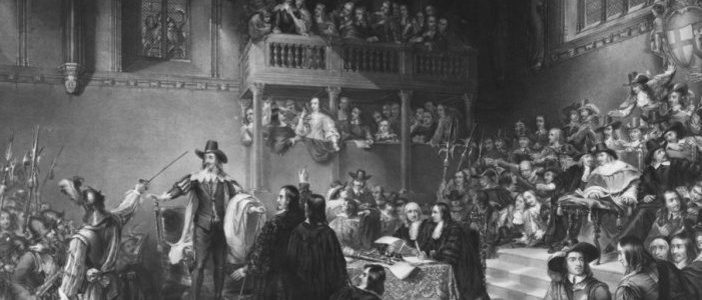

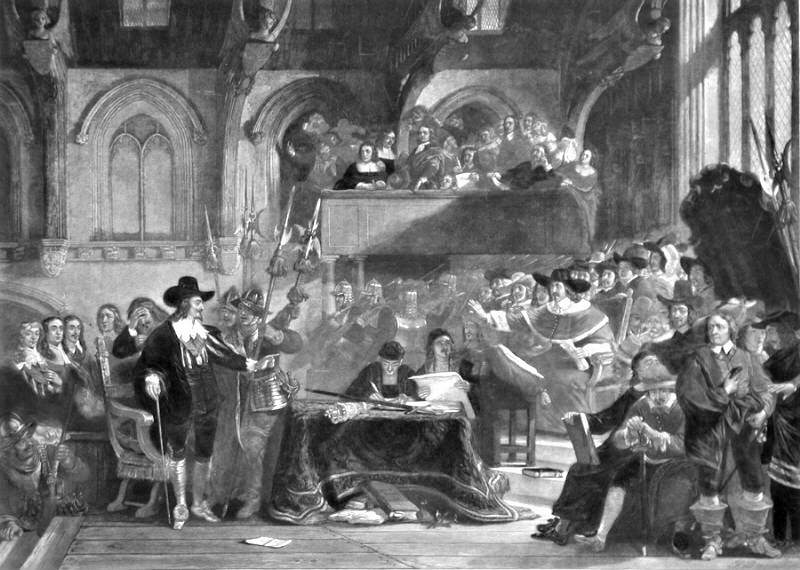

The Trial of King Charles I began on 20 January 1649, at Westminster Hall in London. The Hall was lined with troops and as the King was led in many of the soldiers could be heard shouting -Justice! Justice! While those members of the public present almost universally responded with a chorus of - God Save the King!

Justice Bradshaw sat upon a high bench with the other Judges lined up behind him and to his right were a sword and mace, the seals of his office. The King was partially concealed from the public in attendance by the shape of the dock.

The Court was packed but silence reigned as the charges were read out:

"Out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself, an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people of England, Charles Stuart is hereby charged with treason."

The Courtroom briefly erupted into tumult but once order had been restored the King was asked, how did he plea - Guilty or Not Guilty? The Court rapt, once more fell silent. But Charles, not recognising the legitimacy of the Court to try him, refused to enter a plea. Indeed, he did not even remove his hat which was seen as a mark of disrespect. At one point the top of the King’s cane fell to the floor and rolled towards the bench. There was an awkward pause as Charles waited for someone to pick it up for him. No one did and he was forced to leave his chair, stoop down and do it himself - the disrespect then, was mutual.

Instead of entering a plea Charles, speaking loudly, with great firmness, and without his usual stammer questioned his presence in the courtroom:

"I would know by what power I am brought hither. What lawful power? For there are many kinds of power. Robbers on the highway. When I know by what lawful power I shall answer. Remember, I am your King, your lawful King - and the sins you bring upon your head, and the judgement of God upon this land, think well upon it, before you go from one sin to a greater."

Judge Bradshaw once more demanded that the King enter a plea to which he again requested to know by what authority he had been brought to this place? Bradshaw, increasingly impatient, curtly informed him that he was "brought to trial in the name of the people of England, of which you are elected King." To which Charles replied sharply, if somewhat quizzically, "But England hath never been an elective Kingdom but a hereditary Kingdom these thousand years. I do stand more for the liberty of my people than any here that come to be my pretended judges."

The King’s refusal to plea had stymied the proceedings of the Court and little was achieved on the first day other than the charges being read out and the frequent sharp exchanges between the King and his prosecutors. As he was led from the Court he glanced upon the sword and said in a loud voice “And I am not afraid of that.”

John Cook was angered by the arrogance of the King in refusing to plea, but he also knew that he was acting on firm legal grounds. He was after all being charged with a crime that did not exist at the time it was supposedly committed. No King had ever been accused of betraying his people, and as a King who ruled by Divine Right there was no power in the land superior to him other than God. Parliament, however, interpreted it differently. Their proposal was that the: "King of England was not a person, but an office whose every occupant was entrusted with a limited power to govern according to the laws of the land and not otherwise."

Charles was also aware that according to English law, without a plea there could be no trial. The usual solution to the problem of a defendant refusing to enter a plea was to enact "peine forte et dure", or crushing the body with stones, known commonly as "pressing." It was described thus:

"The prisoner shall but put into a dark chamber, and there be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless where decency forbids; that there upon his body be placed as great a weight as he could bear, and more that he hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three draughts of standing water, that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or till he answered."

This was the law, but no one contemplated forcing the King to endure such an ordeal but by not doing so it rendered the trial illegal. The Prosecutor John Cook knew this, and he was to admit as such at his own trial many years later.

Over the next week Charles was asked to plead on three separate occasions but each time he refused. He still demanded to know by what authority he was being tried. An exasperated Bradshaw told him, "It is not for prisoners to require." To which the King with anger in his voice replied, "Sir, I am no ordinary prisoner!"

The sentiment of the people present seemed to be with the King; Daniel Axtell the Commander of the so-called Black Guard orchestrated his troops to drown out any cries in support of the King with shouts of Traitor and Justice!

An increasingly agitated Bradshaw, aware how unpopular the trial was with the public feared assassination and so wore a steel helmet for protection and surrounded himself with guards. He was prepared to trample over any legal niceties just to get it over with. If Charles would not plead, then he would not be able to call any witnesses in his defence. Dozens of witnesses were called for the prosecution however with each one delivering a damning indictment of Charles's personal rule, his contempt for Parliament and the law of the land, and of his unquenchable lust for blood.

On 27 January, Charles attended the Court for the last time to hear the verdict, and it was possible to hear a pin drop as it was read out:

"This Court doth adjudge that the said Charles Stuart, as a Tyrant, Traitor, Murderer, and a public and implacable Enemy to the Commonwealth of England and the good of this nation, shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body."

There were audible gasps from the public gallery, a woman cried out "Not half, not a quarter of the people of England. Cromwell is the traitor!" It was Lady Fairfax, the wife of Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Commander-in-Chief of the Parliamentary Army, and the man more responsible than any other for the King’s defeat. The muskets of the troops were levelled at her and Daniel Axtell shouted, "Down with the whore" and ordered her be dragged from the Court.

The King now tried to speak but he was not permitted to do so; once a death sentence had been passed the convicted man was deemed already deceased. He was quickly ushered out of the building as the Court descended into chaos and had to be cleared by troops.

Before being dragged from the Court, Charles was heard to shout: "If I am not suffered to speak, imagine what justice other people will have."

Cromwell had got his way and he now desired not just to see the King put to death but the Monarchy with him. Now with the verdict in he was eager to get the job done. He summoned the 68 Commissioners who had passed the verdict to meet with him to collectively sign the King’s death warrant. Many were reluctant to do so and so it took much shouting and a table thumping rage on his part to convince them to do so. One Commissioner even had his hand gripped by Cromwell himself and forced to put pen to paper. Even so, despite all the bullying and all the threats nine of the Commissioners steadfastly refused to sign. They at least would not be condemned before history as Regicides.

King Charles I of England was to be executed on 30 January 1649 just three days after the verdict had been pronounced. His wife and two eldest sons were by now safely abroad and during the little time left to him he was to receive few visitors. instead, the hours remaining he spent in private meditation except for an emotional final visit by his daughter Elizabeth and nine-year-old son, Henry.

On the morning of his execution, he was permitted to walk his pet dog Rogue in the grounds of St James Palace. For his last meal he requested some bread and a single glass of wine. It was a bitterly cold day and he asked to be provided with an extra shirt remarking that, "the season is so sharp as probably may make me shake which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear. I would have no such imputation."

The execution had been delayed when the public hangman Richard Brandon and his assistant refused to carry it out and a replacement had to be found. A frantic search found two men with the required experience willing to be King killers, though the fee had to be increased to £100 and they were to be masked, and even today their identities remain a mystery which undoubtedly saved their lives following the Stuart Restoration.

At 2 pm on 30 January 1649, King Charles I was led from the dark interiors of the Banqueting House into the crisp, bright winter light and to the scaffold that had been draped in black for the occasion. The usual reveries before a public execution were absent, murmurings replaced catcalls, and the many thousands present stood in silence as the condemned man turned to address them:

"I never did begin a war with the two Houses of Parliament. And I shall call God to witness, to whom I must shortly make an account, that I never did intend for to encroach upon their liberties. They began upon me. For the people, I truly desire their liberty and freedom as much as anybody whomsoever. But I must tell you, that liberty and freedom consists in having of Government those laws by which their laws and their God's be most their own. It is not for having a share in Government, Sir, that is nothing pertaining to them - a Subject and a Sovereign are clear different things.

If I had given way to an arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the power of the sword, I needed not to come here, and therefore I tell you that I am a martyr of the people and I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be."

Having completed his peroration Charles removed his cloak and waistcoat and presented them to Dr Juxon who was standing beside him on the scaffold and had been the main beneficiary of his final speech. His last recorded word was Remember, perhaps a reminder to the good Doctor to remember for posterity what he had just said and his son not to forget this day and avenge his death. Then looking down upon the block he remarked that it was a little low and requested that it might be raised. The request was denied. He touched the blade of the axe to test its sharpness before without assistance laying his head upon the block. He then told the executioner not to strike before he had indicated for him to do so by stretching out his arms. He must be permitted to complete his prayers, he said. After a few moments of whispered peroration and quiet reflection the sign was made, and the axe severed the King’s head from his body at a single blow.

A witness later wrote that as the axe fell there was "such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never before and I desire, may never hear again."

As the Executioner held the King’s head aloft many people now rushed forward to dip their handkerchiefs in the blood hoping to acquire the healing qualities of the King's touch.

Following the King’s execution his corpse was laid out in a lead coffin draped in black velvet and taken to Windsor Castle where his head sewn back onto his body.

In February 1650, the Monarchy was formally abolished as "being dangerous and unnecessary to the freedom and liberties of the people of England," followed two days later by the House of Lords. Shortly after, a Council of State was established to run the country with Oliver Cromwell as its Chairman - England had (for the only time in its history) formally become a Republic and a Commonwealth.

William Laud, who had been Archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I, described the King as "a mild and gracious prince who knew not how to be great, or how to be made great." But he was a stubborn man who was convinced that he ruled by the Grace of God alone. Always polite, he was nevertheless diffident and off-hand with people. His stammer and distinct Scottish accent made him unintelligible to some and only added to the general sense of arrogance and unwillingness to listen on his part. Those who knew him and were able to penetrate the cold marble of his regality were loyal to the uttermost, but to most he appeared aloof and out-of-touch.

Even so, following his death Charles was never more popular and his Eikon Basilike, the book of his meditations, became an immediate bestseller. Indeed, so concerned were Parliament at the popularity of the book they commissioned the new Commonwealths primary polemicist John Milton to write a riposte to it but his Eikonoklastes, or image breaker, failed to dent the former King’s popularity.

In fact, the longer the Commonwealth lasted the more the people fell out of love with it; they tired of the constant wars, the arrests and banishments, the abolition of Christmas, the Major-Generals and their moral crusade, so much so that when Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, and power passed to his son Richard, there was no longer any enthusiasm for it and in 1660, following the Treaty of Breda, Charles I's son, also Charles, was restored to the throne as King Charles II, his reign deemed to have started the day after his father's execution.

Much like the Commonwealth before him the new King, also undertook an act of public vengeance and those who had signed the King's death warrant were liable to arrest on the charge of regicide and treason while those who had fled abroad lived in fear of assassination.

On 30 January 1660, the corpses of those regicides who had died including Oliver Cromwell and John Bradshaw were disinterred, beheaded, and hanged in their funeral shrouds from gibbets at Tyburn.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: