Trials of Oscar Wilde

Posted on 28th July 2021

By 1890, Oscar Wilde was the most famous writer in Victorian Britain and his fame was spreading fast. He was known not just for his writing but as a great wit and raconteur. He was clever, he was brilliant and he was showered with praise; but he was as loathed as he was loved especially by those who were the victims of his put-downs.

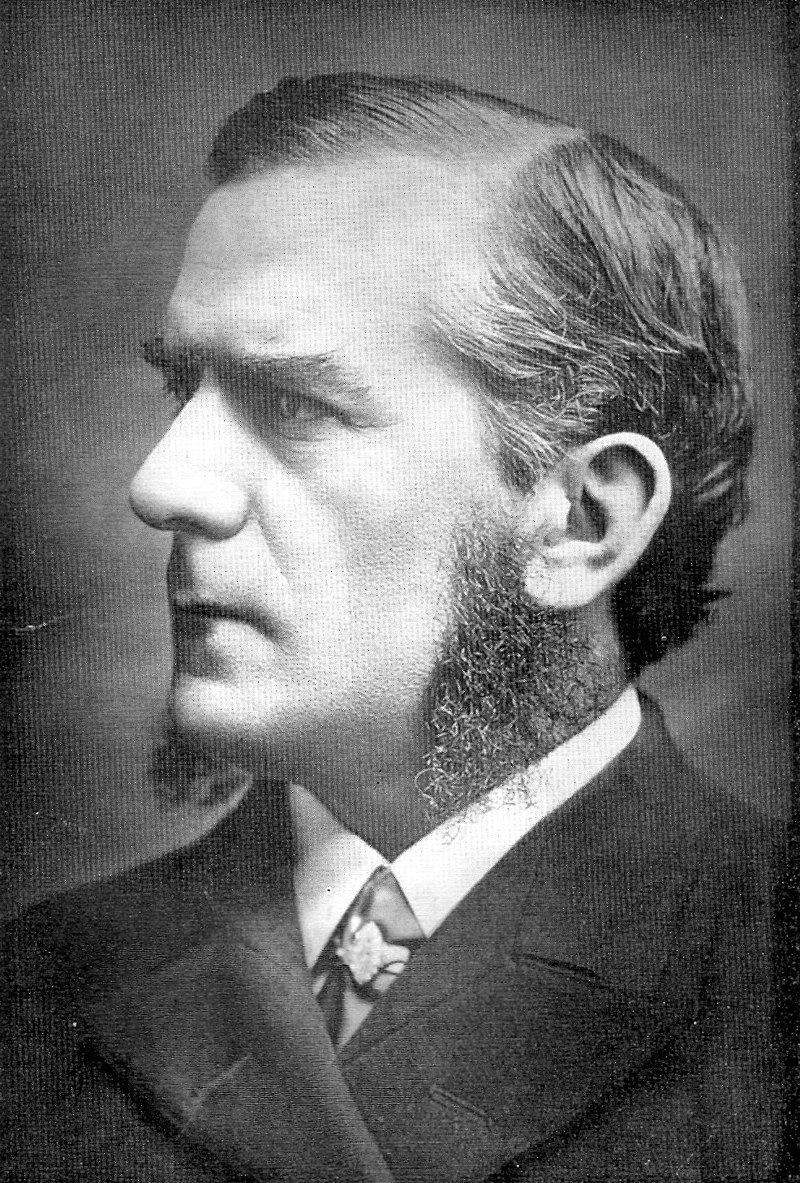

He had been born Oscar Fingal Wills O'Flahertie Wilde in Dublin on 16 October 1854 into the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. His early life was comfortable and cosseted and he was able to pursue his delight in poetry and the written word uninterrupted by travail or tribulation.

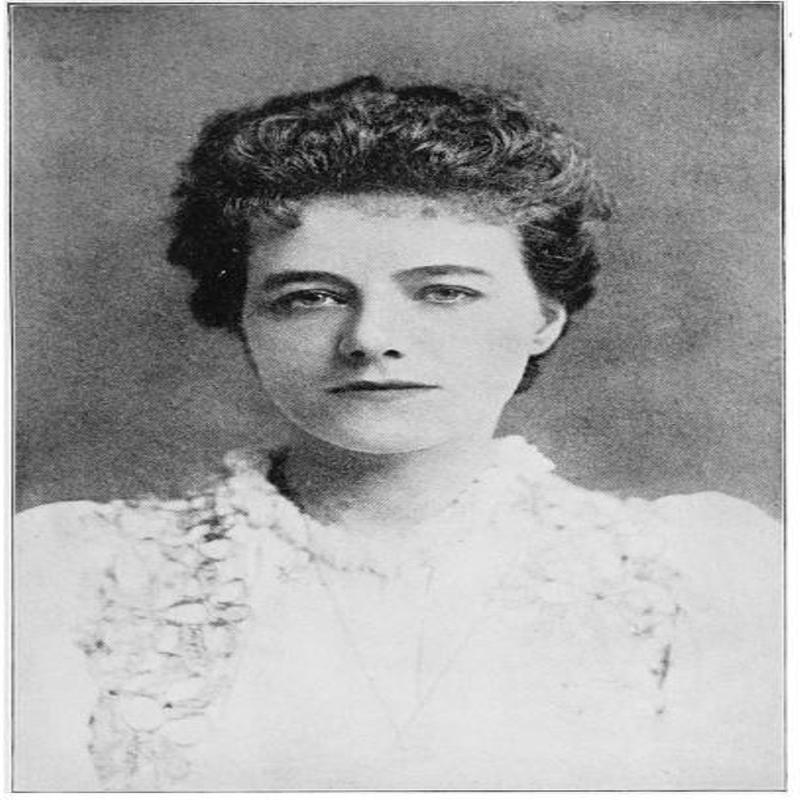

After a brilliant academic career at Trinity College Dublin and Oxford University he dedicated himself to his writing and in 1882 he embarked upon a successful lecture tour of the United States. Upon his return he settled in London and on 29 May 1884 married the well-connected Constance Lloyd by whom he was to have two children. He was a vocal advocate of pleasure and became a leading member of the Aesthete Movement that placed beauty above all things. He was rich, famous and lauded. Life was good and it seemed that it could only get better, but he hid a guilty secret.

Even though marriage had not been forced upon him and he had chosen to propose to Constance he was in fact homosexual. Whether or not up to this point it had been a suppressed homosexuality remains a matter of conjecture though it seems unlikely.

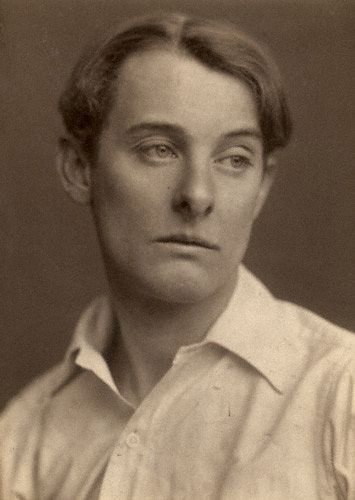

His first known homosexual encounter was with the precocious seventeen-year-old son of rich Canadian parents, Robert 'Robbie' Ross. He had fallen in love with Wilde’s poetry and now determined to seduce the man. It has been suggested by some that he first cornered Wilde in a public lavatory, but it is likely they were introduced to one another at the Marigold Club by a mutual acquaintance and it is widely held now that it was the openly homosexual Ross who first introduced Wilde to homosexual sex.

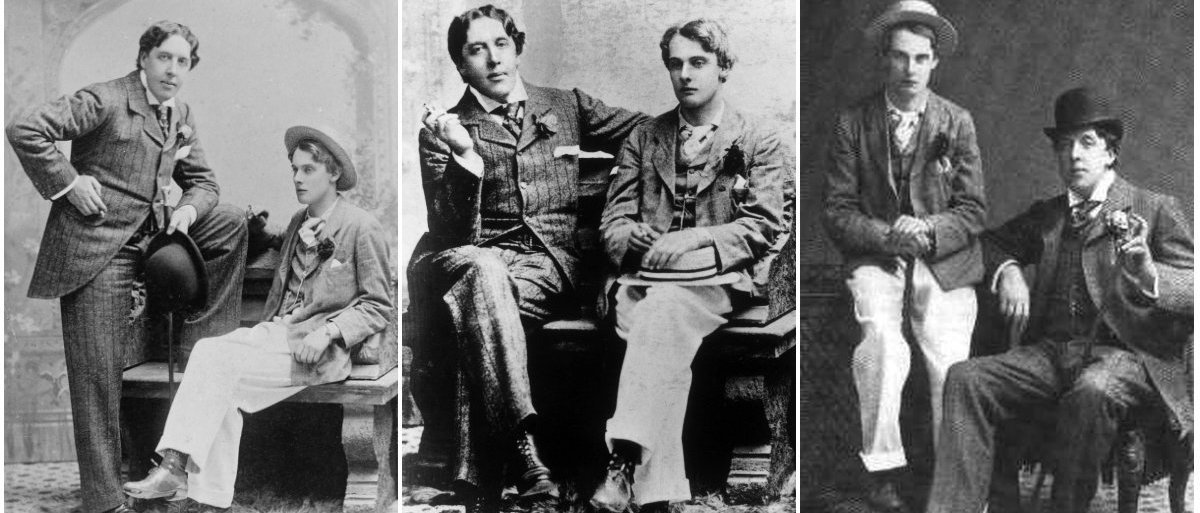

In the summer of 1891, the 38-year-old Wilde met an aspiring young poet Lord Alfred Douglas, also known as Bosie, at a tea party. Wilde was immediately struck by the beauty of this young man sixteen years his junior and he soon began to shower him with gifts. They wrote frequently to one another, often they stayed overnight in each other’s homes and a deep friendship quickly developed but few people suspected anything untoward. Oscar was after all a happily married man with children.

Their relationship quickly moved beyond mere friendship to something more physical and the letters they exchanged became increasingly intimate and suggestive – they were in fact lovers.

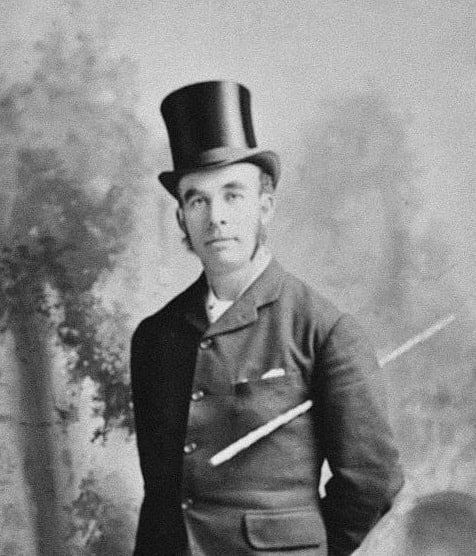

Tongues began to wag as to the true relationship between Wilde and the beautiful young Douglas. These rumours soon came to the attention of Douglas's father the Marquess of Queensberry. The Marquess was a notoriously ill-tempered bully of a man most famous now for putting his name to the original rules of professional boxing. He was determined to end his son's relationship with this vile man, Wilde.

Wilde tried to placate the increasingly furious Marquess even on occasions taking him out to dinner and though he was no doubt charmed after sharing a convivial dinner with the always amiable and easy-going Wilde he could not be swayed from his course of action. Wilde was a homosexual and a sodomite who was seducing his son and his meetings with the effete Wilde only seemed to confirm him in this view.

In April 1894 he wrote to his son, "I am not going to try and analyse this intimacy, and I make no charge, but to my mind to pose as a thing is as bad as to be it." Douglas was dismissive in his response and as a result the Marquess threatened to cut-off his allowance.

While still a student at Oxford University Bosie had given an old suit of his to a down-and-out he knew by the name of Alfred Wood. In one of the pockets Wood found several letters that had been sent to Douglas by Wilde. They were graphic in their content and Wood extorted £35 from Wilde for the return of most but not all the letters. Wilde was later to suggest that the money had been a gift though it was clear it was not.

The Marquess was now often to be seen in London accompanied by a prize-fighter threatening anyone he thought was helping to facilitate his son and Oscar's relationship. Restaurant owners, hotel porters and cab drivers all became subject to a tongue-lashing and threats of a whipping. He even turned up at Wilde's house in Chelsea accompanied by his minder to threaten him in person. But Oscar was a big man not easily intimidated and after a furious exchange of views he threw the Marquess out declaring, “I do not know what the Queensberry rules are but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot on sight.”

A series of angry and threatening letters were then exchanged between father and son in one of which the Marquess accused Bosie of being a reptile and no son of his to which Bosie responded, “If O.W was to prosecute you in the criminal courts you would get seven years servitude for your outrageous libels.” It was a sign of things to come.

On 14 February 1895, Oscar Wilde's new play The Importance of Being Earnest opened at the St James Theatre in London. The Marquess of Queensberry had threatened to disrupt the opening night by making his accusations public. To prevent this Wilde hired private security guards to ensure that he was denied entry to the theatre. He did indeed turn up but unable to gain access he left after a few hours in a huff and the opening night was another triumph for Wilde - there seemed be no stopping him now.

Frustrated in his attempts to make his accusations public four days later the Marquess turned up at Wilde's Club, The Albermarle. Wilde was not present, so the Marquess left a calling card inscribed with the words “For Oscar Wilde, Posing Sodomite."

Wilde was uncertain what to do about the insult. Bosie and his friends insisted that he bring a prosecution for libel, others urged caution. Eventually, Wilde, along with Bosie and Robert Ross visited the solicitors Travers Humphreys to begin a case of libel against the Marquess of Queensberry. On 2 March, the Marquess was arrested.

Prosecution Counsel Edward Clarke was appointed to bring the case and aware of Wilde's reputation for having bohemian tastes sought reassurance that there was no foundation to these rumours. Wilde insisted that there were none, none whatsoever.

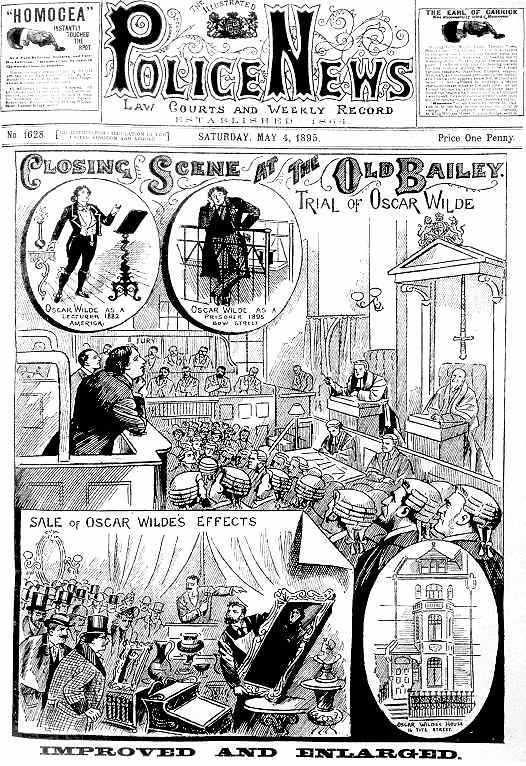

The Trial began at the Old Bailey in London on 3 April 1895. The Gallery was packed, particularly with the large number of journalists present.

There was an audible gasp when the flamboyant 6'4" inch Oscar Wilde swept into Court wearing a wide-brimmed hat, a chiffon scarf and decked out in an array of colours. He appeared relaxed and confident in stark contrast to the Marquess of Queensberry who seemed somewhat tense and was in earnest conversation with his legal team.

Edward Clarke began the case by trying to put to bed once and for all the absurd allegation that there was anything untoward in the relationship between Wilde and the defendant’s son. In reference to the letters that were produced as evidence by the Defence Counsel he stated that Wilde was a poet. The feelings expressed in the letters might appear somewhat extravagant to the common man more used to commercial correspondence but for Wilde words were his art. The love expressed was a poetic love. They were "the expression of true poetic feeling with no relation whatsoever to the hateful and repulsive suggestions put to it." It was an impressive opening to the prosecution case, but it would soon be undermined by Wilde himself.

Taking the Stand for the first time he immediately began with a lie. Asked to confirm his age he stated that he was 38 when he was in fact 41. It was not a promising start.

The Defence Counsel headed by Sir Edward Carson, an old sparring partner of Wilde's from their days together at Trinity College Dublin, accused him of writing books with immoral homosexual themes. To which Wilde replied that there was no such thing as an immoral book. Books, he said, "are merely well-written or badly written." Asked then if there was no such thing as an immoral or perverted book how would he describe The Picture of Dorian Gray with its theme of homosexuality running throughout? The still confident and ebullient Wilde replied that it could only be considered so by "brutes and illiterates, philistines and the incalculably stupid.” When Carson suggested that one of the letters he had written to Douglas was no ordinary letter, Wilde replied that indeed it was not, it was a "beautiful letter."

Wilde's answers from the Stand were intended to be creative and witty but he came over as being smug, complacent, arrogant and vain. The journalists loved it, but it did not impress those who mattered.

Carson now produced a series of expensive gifts that Wilde had given to his young male friends. These gifts, he said, had been bought for lower-class youths, inarticulate, ill-educated, even in some cases illiterate. This was not the expression of intellectual love of which he spoke. Where was the intellectual justification in the company of such people? Wilde tried to make light of the question but for the first time he seemed ill-at-ease.

Yet the procession of disreputable young men upon whom he had lavished gifts brought a darker and more sinister tone to the case. He now appeared more hesitant in his answers and occasionally stumbled over his words.

Carson proceeded to ask Wilde about a young man he knew, a sixteen-year-old youth by the name of Walter Grainger. "Did you kiss him?" he asked. "Oh dear, no! " Replied Wilde, "he was a particularly plain boy." The answer had provided Carson with the opportunity had been looking for and he was determined to press home his advantage: "Was that the only reason you did not kiss him? If not why did you mention his ugliness? Why? Why?" The entire Court gasped as a clearly flustered Wilde was unable to answer.

Carson announced that he intended to call a number of these young men to testify on the morrow. With that the Judge adjourned the Court for the day.

Wilde's Defence Counsel Edward Clarke now took him to one side and told him that since the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 had made any sexual encounter between two men illegal on the grounds of gross indecency to continue with a case he was now almost certain to lose would leave him vulnerable to prosecution: "It is almost impossible in view of all the circumstances to convince a jury to convict a father who was endeavouring to save his son from an evil companionship. “He advised him to drop the prosecution. Wilde agreed.

In the meantime, Queensberry’s solicitor had forwarded to Scotland Yard the statements of the young men Sir Edward Carson intended to produce in Court. There was now a delay in the closing of the case for libel and the issue of the warrant for Wilde's arrest.

Perhaps it was hoped that given his fame Wilde would take the opportunity to board the boat-train for the Continent. Wilde however hesitated. He seemed to be in a state of shock. His friends, including Bosie, advised him to flee. His mother insisted that he remain and fight the accusations like a man. In the end he did nothing except complain that Carson had prosecuted him with “all the relish that is the preserve of an old friend.” He was arrested soon after.

The Trial of Oscar Wilde on charges of gross indecency with young men began at the Old Bailey on 26 April 1896.

It was now a very different Oscar Wilde who took the Stand, the confidence and flamboyance of earlier had now gone. He was nervous and hesitant and spoke quietly as if he was afraid of his own words. Only in his response to the question posed by the Prosecutor Charles Gill regarding the use of the phrase "the love that dare not speak its name" in a poem by Lord Alfred Douglas could Wilde clearly be heard by the gallery as he gave a spirited defence of the beauty of the intellectual love between two men that was the noblest of affections:

"The love that dare not speak its name" in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the "Love that dare not speak its name," and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it."

Wilde’s words received a mixed reception with loud applause accompanied by both jeers and howls of derision.

After three hours of deliberation the jury decided that it could not reach a verdict and the case was dismissed. There would have to be a re-trial.

Released on bail Wilde appeared more relaxed and confident that he would be spared the nightmare of yet another Trial and the ruin of his career.

Edward Clarke had been telling his colleagues in the legal profession that his client had suffered enough and that it was time to let go. Most seemed to agree, but the Government did not. It was determined that the prosecution should go ahead. Why the Government decided to get involved remains a mystery.

It had been rumoured that the Prime Minister Lord Roseberry had been having a homosexual affair with the Marquess of Queensberry's other son, Francis. He had been killed in a shooting incident that was officially declared to have been an accident but was believed by many to have been suicide. It is possible that Queensberry threatened to reveal their relationship should the Prime Minister refuse to proceed any further with the case.

The Prosecution at Oscar Wilde's Second Trial was led by Britain's senior Legal Officer the Solicitor-General Sir Frank Lockwood. Unlike his predecessor Sir Edward Carson, who had enjoyed jousting with his old adversary Wilde, Lockwood dispensed with any such frippery. Instead, he struck at the heart of the case: “Wilde, he said, is a man of culture and literary tastes and I submit that his associates should have been his equals. Instead, he chose to have relationships with these illiterate young boys.” Why was the question, and the inference was clear. Oscar Wilde was neither an artist nor a great wit but a sodomite plain and simple, and sodomy was against the law. He painted a picture of Wilde as a sexual predator who used his fame and wealth to seduce vulnerable young boys into satisfying his perverted sexual desires.

Even though, it seemed at times as if Wilde’s real crime was not having solicited young men for same sex gratification but to having done so with young men outside his class, a guilty verdict was inevitable.

On 25 May, Mr Justice Wills sentenced Wilde to the maximum term permitted for such offences - two years hard labour. In his summing up he remarked: "I believe the sentence is totally inadequate for a case such as this. It is one of the worst cases I have ever tried." Wilde tried to speak in his defence, but his words were drowned out by the jeers and celebrations from those present as the Court broke up to shouts of Shame! Shame!

Along with his sentence of hard labour he was also made to pay the cost of the Court case and the police investigation.

Oscar Wilde was first imprisoned at Pentonville and then at Wandsworth. It was a harsh environment, he was working ten hours a day, sleeping on a hard bed, the food was basic, and he was frequently cold. Much of his time he spent in the prison hospital. Eventually, his friend the Liberal M.P Richard Haldane managed to get him transferred to the less harsh Reading Jail.

During his transfer while waiting on a station platform he was abused and spat upon by other commuters. He was later to say it was this incident more than any other that upset him.

Bosie made no effort to communicate with Oscar during his confinement which hurt him deeply and it appeared their friendship was at an end. In his prison cell he wrote De Profundis or From the Depths in which he mused at length upon their relationship expressing both his great affection for and no little criticism of, his former lover.

Released from prison on 19 May 1897 Wilde immediately went into a self-imposed exile in the French countryside before later moving to Paris. Despite the torment he endured in prison he refused to feel sorry for himself and wrote at great length about his experiences: "Ones ordeals fill the soul with the fruit of experience, however bitter it tastes at the time." His career however lay in ruins. His writing was now literary poison, and he became reliant upon others for money.

His wife, Constance despite the neglect, the many years of public humiliation, the divorce and her refusal to allow him access to their children did at least provide him with money when she could but then she died a little under a year after his release.

Bosie stayed for a while with Oscar in France until his visits were curtailed by the threat of his father to sever his allowance. Their reconciliation had not been a success in any case and upon receiving access to his father's money Bosie refused to help Oscar financially or provide him with a pension as requested.

The last few years of Oscar Wilde's life were spent in relative poverty. With few visitors he could often be seen wandering the boulevards of Paris alone or in local cafes where he would lose himself in copious amounts of alcohol. With his health declining he remarked: "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go."

Ignored by the public and abandoned by friends and family Oscar Wilde died of meningitis on 30 November 1900, aged 46, a broken and forgotten man.

In later life Lord Alfred Douglas was to turn against his old friend and ex-lover so unlike Robbie Ross who remained devoted to Wilde the man and to his legacy. Indeed, he was at his bedside as he passed away. The loyalty displayed by Ross only embittered Douglas even further and he was to attempt repeatedly to have him prosecuted for having committed homosexual acts.

Following Wilde’s death, Douglas was to describe him as evil and over time became rabidly homophobic, highly litigious and an enthusiastic anti-Semite. Despite this he was to have a long and successful career both as a poet and an academic.

He died on 20 March 1945 in Lancing, Sussex, of heart failure, aged 74 – though some might suggest his heart had failed him much earlier.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: